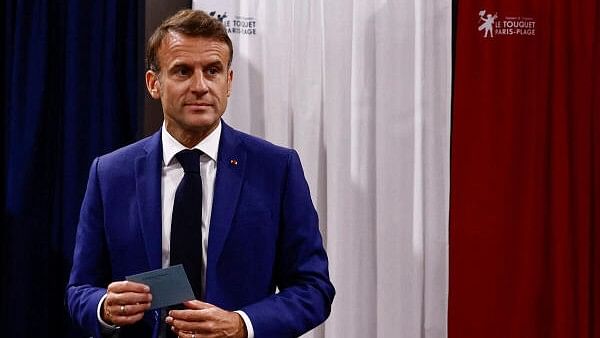

French President Macron votes in the first round of the 2024 snap legislative elections.

Credit: Reuters Photo

By Lionel Laurent

What’s the French for “stop the steal”?

Far-right leader Marine Le Pen this week has taken on a Trumpian tone ahead of Sunday’s final round of parliamentary elections, accusing President Emmanuel Macron of cooking up an “administrative coup d’Etat” through official appointments that would restrict her party’s ability to govern if she wins a majority. Talk of a coup is nonsense, but it highlights a rising challenge for Le Pen’s chances of taking power.

Le Pen and her center-right ally Eric Ciotti — who said Macron was “confiscating democracy” — are clearly priming their followers for potential disappointment and a long-haul battle versus the elites, as left and center parties try a last-ditch tactical coalition to outvote the far right. After weeks of slinging mud at each other, politicians from Macron’s centrist camp and the broad, left-wing New Popular Front Alliance have pulled candidates out of more than 200 runoffs to avoid splitting the vote in Le Pen’s favor. Financial markets are now betting that Le Pen’s final seat tally will be well below the 289 needed for an absolute majority. It’s a fair bet.

Think of this as Macron’s last risky roll of the dice to keep Le Pen out. Parisian elites, a kind of last holdout for pro-Macron forces, seem to have finally woken up to the risk posed by right-wing populists to France’s public finances, European influence and social fraternite. Various politicians, officials and financiers are said to be throwing their hats into the ring should an alternative coalition government get cobbled together.

The leap into the unknown that Le Pen represents makes these efforts worth trying. But such a shaky coalition brings its own risks. This is all very new territory for the Fifth Republic: Former European Central Bank Governor Jean-Claude Trichet told Bloomberg this week that while Italy was used to technocratic governments, the French would want to see real political stripes. Hence why an anti-Le Pen coalition might not necessarily unite the approximately 66 per cent of voters who didn’t vote for her: It would put Macron’s centrists in the same alliance as big-spending Socialists, anti-nuclear Greens and deficit-hawk Republicains. “Le Stitch-Up” might see a lot of voters staying home.

And given such a strained coalition would be living on borrowed time, France’s populist moment might still only be delayed rather than defeated. Le Pen will jump at the chance to demonize the establishment from the opposition benches, just as her Holocaust-denying father Jean-Marie mocked the governing left and right parties as indistinguishable (creating a portmanteau acronym “UMPS” out of their initials.) Privately, Le Pen and her 28-year-old No. 2 Jordan Bardella might even be relieved at dodging the bullet of government — their contradictory and vague proposals on what they would do once in power have failed to rally political and economic heavyweights to their cause.

All of which poses the question: Is all this really better than the alternative? Some might argue that a fragile establishment coalition that voters haven’t asked for and that exists nowhere on the political map will fuel Le Pen’s talk of an anti-democratic coup. Would it not be better to drop the cordon sanitaire and take the risk that the far-right comes to power? After all, plenty of populist parties have crashed and burned after tasting power, from Italy’s Five Star Movement to Greece’s Syriza.

I’m not so sure. A far-right party in the centralised French system is uncharted territory and could do a lot of damage, from media interference to fiscal showdowns with European partners. Professor Ben Crum, of the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, gives the example of Poland’s PiS, whose controversial judicial reforms and European rule-of-law fights have left deep scars. He adds that delaying Le Pen’s arrival to power also increases the chances that other credible leaders will emerge to fill the void left by Macron’s withering centrist movement.

Some good can come from this dice roll, in other words. But it all depends on French voters being willing to align their choices with their elected representatives. If calls for a republican front turn out to be just empty rhetoric, France’s crisis runs deeper than we think.