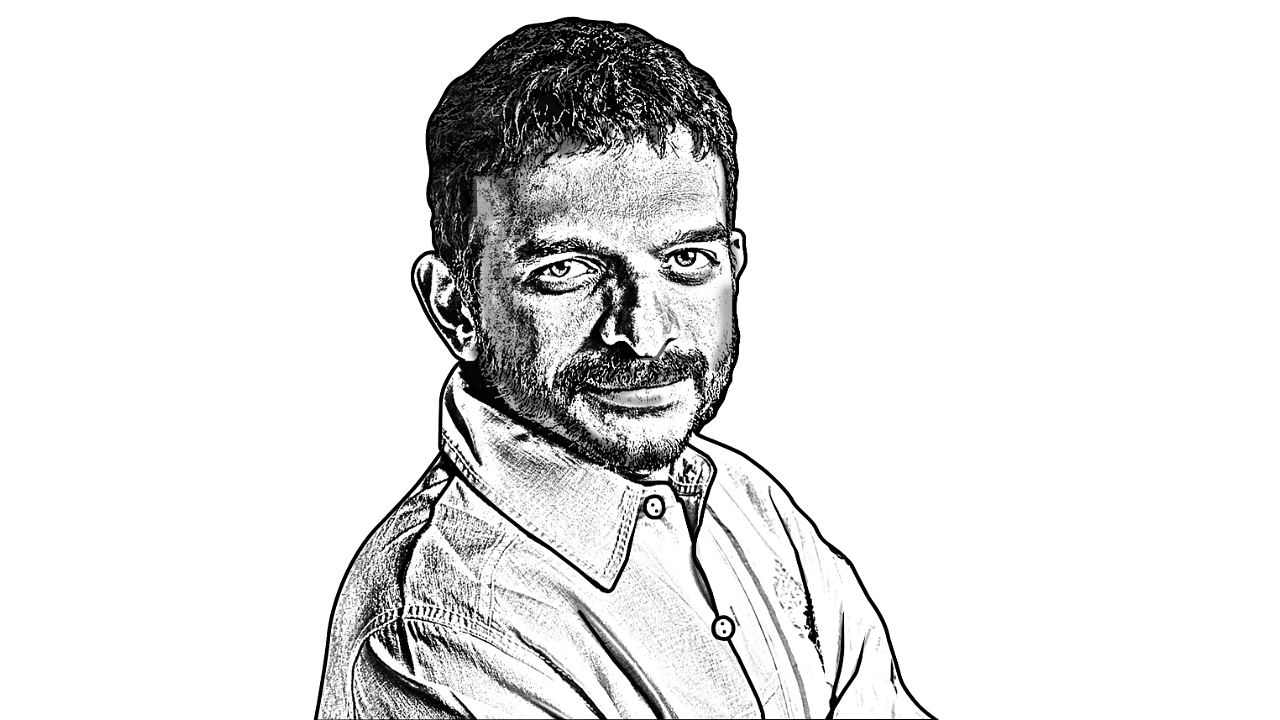

T M Krishna. The mind questions, the music moves, the mountains beckon.

@tmkrishna

For weeks now, N R Narayana Murthy’s statement on the 70-hour work week and his comments on post-WWII Germany and Japan have been doing the rounds. Some from the corporate world disagreed with him and others seconded his opinion, but Murthy has not retracted the statement. He has only reiterated the same, with his wife Sudha Murty joining in. They have been asked about work-life balance, spending time with each other, and Murthy’s absence as a father. Their answers have been similar to what I have heard in my family. Typical middle-class Brahmin family observations of how life should be.

The idea that one must work ‘hard’ at any cost has been drilled into the Brahmin middle-class mind for generations. Study hard, secure admission in a good college, get married, provide for the family, and raise your children with the ‘correct’ values. Whatever laughter and happiness can be bundled within this targeted journey is acceptable. Pleasure is a bad word. Seeking leisure is utter extravagance and to be avoided. A corollary to this way of thinking -- which the Murthys do not specifically articulate but is inbuilt in their thought process -- is the judgement of those who do not adopt such a lifestyle as lazy, probably mediocre, free-loaders, or those who are wasting their God-given talent. The dangerous word hidden behind such views is ‘merit’.

Murthy’s tone is similar to those who believe ‘merit’ should be the basis for everything. If you put your head down and work hard, success will come your way. The baseline from which each individual emerges, the centuries of accrued social, cultural and intellectual capital is ignored, and a conducive home environment taken for granted. Murthy emphasises that he studied on scholarships and many of his friends also benefited from subsidized education. He is subtly informing us that they all came from humble beginnings. Sudha Murty says as much in an interview where she states that they do not come with any connections and wealth, referring to themselves as ‘ordinary’ people. He only speaks of the ‘poor’ and how we owe it to them to work our butts off! He does not refer to the socially marginalised. In this silence, I hear that oft-stated privileged caste quote: “We never bothered about caste.”

Caste-privileged individuals do not understand the difference between economic deprivation and social discrimination. Once you do not have money, how does it matter if you are man, woman, transgender, Brahmin or Dalit? In their imagination, the lack of financial wealth is a leveller. Even if they acknowledge a difference, it is still considered secondary. They expect transpeople and Dalits to fight the system and make it in life. If they do not, then it is largely their failing. In order to prove their point, success stories from marginalised communities are quoted, without taking into account their struggles or the fact that they are exceptions. In this, all conversations on our internally rigged social system is buried. Essentially, this perspective is casteist and anti-caste reservation.

There could be something we are all missing. Murthy’s life has been in the technology space, which has been dominated by individuals with caste privilege right from its early days, and continues to be so even today. It is likely that his social circles were comprised mostly of people from within the same spectrum. All this leads to homogeneity in thought and practice. Those raising the issue of work-life balance also come from the same kindred social location. Though Murthy is speaking in generalities, in his mind, the image of the individual he is addressing is a young Narayana Murthy! Outside that sphere exist the poor on one side and the super-rich on the other. Murthy may be wealthy but he still considers himself middle-class!

What does working 70 hours mean? I am an artist and writer. For both these endeavours, leisure -- that is actually doing ‘nothing’, just observing, being with oneself -- is essential. But, in Murthy’s book, I am whiling away my time. Once, a middle-class bank employee told a musician that she lives an easy life, which involves practicing for a few hours and singing a concert. But he works for eight hours every day for five or six days a week. Murthy probably feels the same way about people who write poetry, sing, dance or act. Furthering this thought is the notion that the arts are for the privileged, to be enjoyed in limited quotas after you have secured for yourself roti-kapda-makaan. The presence of so much art among the underprivileged does not even enter their mind. All that is only handicraft, handloom and folk that needs to be corporatised. I also wonder what individuals who are forced to work for more than 70 hours a week by corporations should do.

But why do we give so much importance to Murthy’s words? He worked diligently, built a very successful company, and rose up the economic ladder. There can be no doubt that many benefitted economically from its success. But Murthy is not a person of ideas that emanate from conscious, deliberate engagement with the larger society. Learning that teaches us that there is much more to life beyond working 70 hours a week. But we are all enamoured by the likes of Narayana Murthy and Sudha Murty. They, we believe, have all the answers in single-line mantras, much like self-help books.

People who work in the social sphere, especially those who come from difficult backgrounds, do not interest us. Their world views are boxed within their specific social identity. Whereas Narayana Murthy’s is considered universal and ideal. Maybe the problem is with us!