Technology has seen a bloodbath recently, with massive, unprecedented layoffs in the crème de la crème of tech, often abbreviated as MAANG (Meta-Amazon-Apple-Netflix- Google), as well as in some of the hottest start-ups in Silicon Valley, including Stripe, Doordash and many others. In all of these, a common refrain and “apology” (to the people they laid off) from the CEOs of the companies is that they “grew too fast”.

Now, you have two options here. Either you believe that some of the world’s smartest people, backed up by other very smart people backed by some of the best financial science money can buy, all made the exact same mistake at the exact same time -- of growing too fast during Covid, in the way middle-aged men find their waistlines. Or you suspect that maybe, there is something else going on.

In the days of old, a business’ success was measured in the amount of money it made as profits. If it kept on making losses, investors left, if it made a profit, investors piled on. Of course, money needed to be raised from the market, through debt, since one could not operate purely out of earned capital and one also needed money for expansion. But the money raised (or the ease of raising money) was based on current profits, which again depended on the actual demand for the product in the market. I say “days of old” but most companies in the world still work on this model. They survive because there is concrete and current demand for their products -- be it medicines or televisions or groceries or clothes. And, yes, they raise money for new initiatives, but it is usually based firmly on what they currently do, what products sell, and most importantly, what products make money.

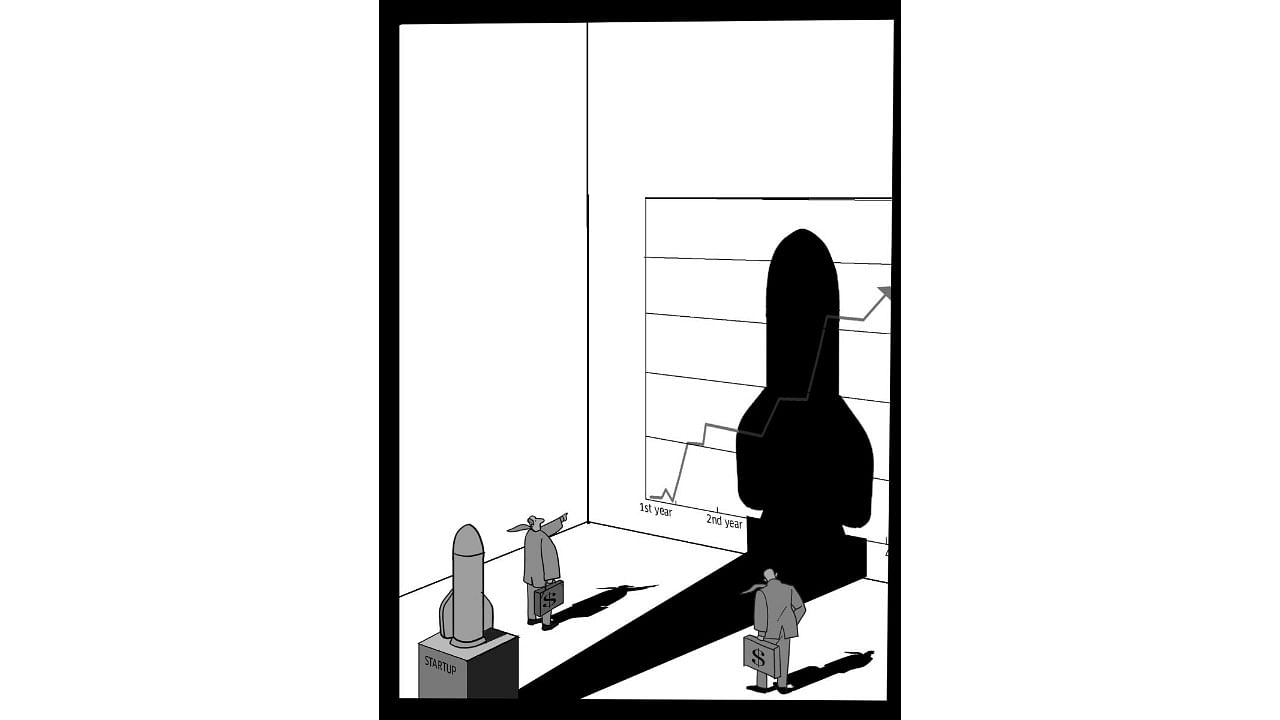

In the new model though, born out of a marriage of Wall Street and Silicon Valley, the understanding is that the “tech model” is in generating demand for a product, even if it does not exist now. So “concrete and current demand” as the metric for valuation is replaced by “potential for demand” and the “potential for a business to service the demand”. The primary goal for the CEOs is then to demonstrate the “potential for a business to service the demand”. So, the way it works in this model is:

1. You have an idea.

2. You develop a prototype, financed by your own money.

3. Your prototype acquires users.

4. Once you acquire a certain number of users, people invest in you. You now have a product.

5. The more users you have, the more you understand what users really want, and you develop the product further.

6. If not profitable yet, keep doing steps 4 and 5.

A company’s “potential for a business to service the demand” is measured by the people currently using it, in much the same way we measure a person’s worth by the number of followers they have on social media and the likes they get. Specifically, Wall Street and investors measure a company’s growth, how fast their users increase, they predict how much it will increase next quarter, and if it meets or surpasses the expectation set forth by Wall Street and investors, the company is “doing great”, i.e., meeting its objective, and more money flows into it.

Also Read: Success rate of startups in India relatively higher than rest of world: Goyal in Lok Sabha

In the new paradigm of business, profit is not as important as the acquisition of users and even the prospect of user acquisition, also known as “buzz”. That is why so many unicorn start-ups bleed money to acquire users, and that is why so much of modern start-up culture is about publicity and big talk. Without the hype, there is no perception of growth potential, and consequently, money does not come in from the market.

So, how is the real money made here? If you look at the list above, steps 4 and 5 are repeated, the investors in the (n-1)th round get their return on investment from the money raised in the nth round, and so yes, money is made, insane amounts of it, just not in profit -- and that someone at the end is left holding the can.

Now, it is not that all companies falter before they reach step 6, some do actually make profits, but most crash and burn a lot earlier, but not before making a few people very, very rich.

Coming back to the “growth mistake”, Covid-19 came along, locking down the world, and while overall it destroyed many of the old businesses which worked on actual demand for their products, it was a boon for many of the companies that were in the business of demonstrating potential for profit. As people stayed home, e-commerce rose, and every CEO with projections for growth found those projections met, exceeded, and then some.

And since they had already met a very high bar and exceeded it, they were patted on their back, they took home record compensations, and then the nth round of investment was huge. There was another reason for the hugeness of the nth round: interest rates were very low. No one plays this game with their own money, they borrow from the market, and so, combining these two factors -- easy money and unprecedented growth – Covid-19 led to a huge capital influx, and so they grew. In order to grow this fast, they needed to hire, so these companies hired people from the market, often at inflated salaries to meet projections, leading to last year’s great shortage of skilled tech labour. Now we see the elastic springing back, as those hired in order to show the capability to grow, are being returned to the labour pool, upending the lives of engineers on H1-Bs and others who did not make a killing on the upside but now take the worst impact of the downside.

But what about the Amazons, the Metas, and the Googles? These are consistently profitable companies, with demonstrable demand for their existing products, and they are not single-product start-ups. They have multiple, nearly independent, lines of business, some of them quite speculative in their “potential for growth” categories, and sometimes the more profitable parts of the business are used to bankroll the expensive bets in the growth areas.

But sometimes they do not, and the speculative branches are allowed to die while the main trunk remains untouched. This is why Google became Alphabet and Facebook became Meta -- to more clearly isolate the foundational parts of the business from the speculative -- and Amazon’s marketplace losses are subsidised by their cloud business. And when easy capital is not available from the market, they too shed their flab to compensate for growth promises made, in the same way that smaller start-ups do, because ultimately it is the same valuation model, and the same operating principles, and as we see, the same CEO apology.

(The writer is a computer scientist and novelist based in California)