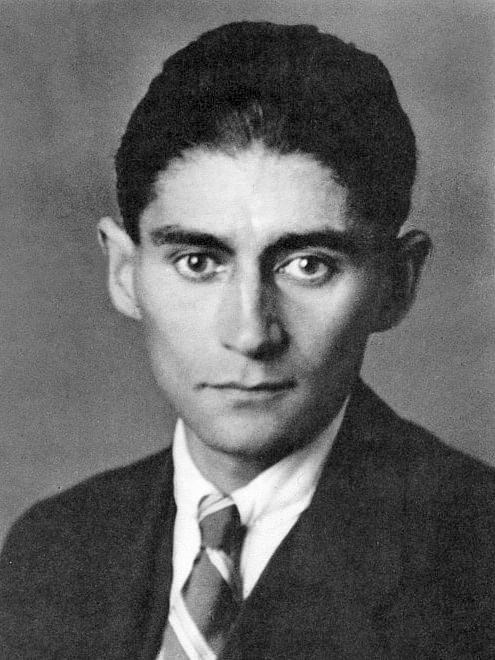

It’s a well-known story. An anxious, agonised author, dying prematurely young, writes to a close friend asking him to burn his manuscripts, diaries, and letters. The friend, convinced of the writer’s greatness, ignores the request. Instead, he zealously edits, publishes and promotes the work. With this act of disobedience, Max Brod introduced the world to the tales and notions of Franz Kafka.

The story has a sequel, though, and last week, a district court in Zurich brought it to a conclusion. Upholding an earlier Israeli verdict, it ruled that the contents of safe deposit boxes in the Swiss city could be shipped to Israel’s National Library. The dispute was between the State of Israel and the family of the late Esther Hoffe; at stake was the Kafka cache that Max Brod carried with him when he fled Nazi-occupied Prague for Tel Aviv in 1939.

Brod had bequeathed the papers to Hoffe, his secretary, and since then she, and later her surviving family, resisted attempts by the Israeli state to obtain the works. (In 1988, in fact, Hoffe went ahead and sold the original manuscript of The Trial to the German Literature Archive in Marbach for $1.8 million.) The Zurich judgement, however, completes the acquisition of nearly all of Kafka’s known works.

Despite headlines to the contrary, Benjamin Balint, research fellow at Jerusalem’s Van Leer Institute, says that it’s “very unlikely we are going to discover an unknown Kafka masterpiece in there, but there are things of value.” In his Kafka’s Last Trial, which chronicles the case, he makes the necessary point that the dispute isn’t simply about ownership of the papers, but centres on the broader issue of cultural heritage: “Does Kafka’s beguiling writing belong to German literature or to the state that regards itself as the representative of Jews everywhere?” This, of course, dovetails with the much-debated point of how much Kafka’s own conception of Jewishness informed his work.

Whether grounded in religion or not, Kafka’s work flies above theological and national nets. Max Brod emphasised the spiritual aspects, but in Adam Thirlwell’s apt pun, it is important not to read Kafka too Brodly. One imagines the writer himself hurriedly retreating into his room; as he once wrote to Felice Bauer, his then fiancée: “I consist of literature, I am nothing else and cannot be anything else.”

His insights into the nature of authority and violence are unquestionably universal. As Auden said, “Kafka is important to us because the predicament of his hero is the predicament of the contemporary man.” Driving home the point, Vaclav Havel has spoken about recognising feelings of culpability, alienation, and the absurd after reading Kafka. And for Roberto Calasso, Kafka is aware of the overlap between the powers of a castle to elect, and of a trial to punish, “but this wasn’t only a matter of Jewish heritage. It has to do with everyone, and all times.”

Obscure hierarchies and bewildered subservience apart, the strangeness of Kafka’s work has often drawn comment. There is attention to detail and being in the world, but there are also transformations of man into insect, reports from apes and mice, devices that inscribe words into flesh, and performers who turn fasting into art. These shifting registers of reality arise from writing that takes the metaphorical literally, and vice versa. The effect is incongruous and familiar at the same time.

Such are the qualities that have led many to claim that in literature, Kafka is unique: he has no precursors. Borges’s valuable insight, however, is that Kafka creates his own precursors. We read those that came before him differently because of what he has revealed, enabling us to trace a “continual dialectic of strength and weakness”, in Michael Hoffman’s words.

It’s a dialectic that shows no signs of resolution. This, after all, is a world of the Big Uneasy, where people are turned into vermin in the course of a single speech. Where victims of communal attacks are themselves suspected of crimes. Where families who have stayed in a country for generations are asked to prove their credentials. Where those accused of breaking the law ask for votes so they can become lawgivers.

Perhaps, though, the times were always impenetrably strange. As John Banville once remarked, the world was Kafkaesque before Franz Kafka; all he did was contribute the adjective. To take a serendipitous example, dipping into Simon Critchley’s new book on Greek tragedy, one finds him asserting that this ancient art reveals a "conflictually constituted world defined by ambiguity, duplicity, uncertainty, and unknowability, a world that cannot be rendered rationally fully intelligible through some metaphysical first principle or set of principles, axioms, tables of categories, or whatever.”

Now that’s Kafkaesque.

(Sanjay Sipahimalani is a Mumbai-based writer and reviewer)