Politicians use humour to imbue the audience with a particular image. Humour is sometimes used in the House to add levity and attract the attention of other members and a larger audience. It's also used to bring members closer together (especially on the opposition side). As a 2014 thesis noted, “some MPs have used humour as a relational management strategy (and...) to procure more time from the Chair”.

When in the Opposition benches, Indian lawmakers have generally used wit and humour more effectively. It allows them to pack more punch into their arguments while also alleviating tensions and tempers. This could lead to a productive debate in Parliament in a dignified atmosphere. Maybe members should try this during the next session.

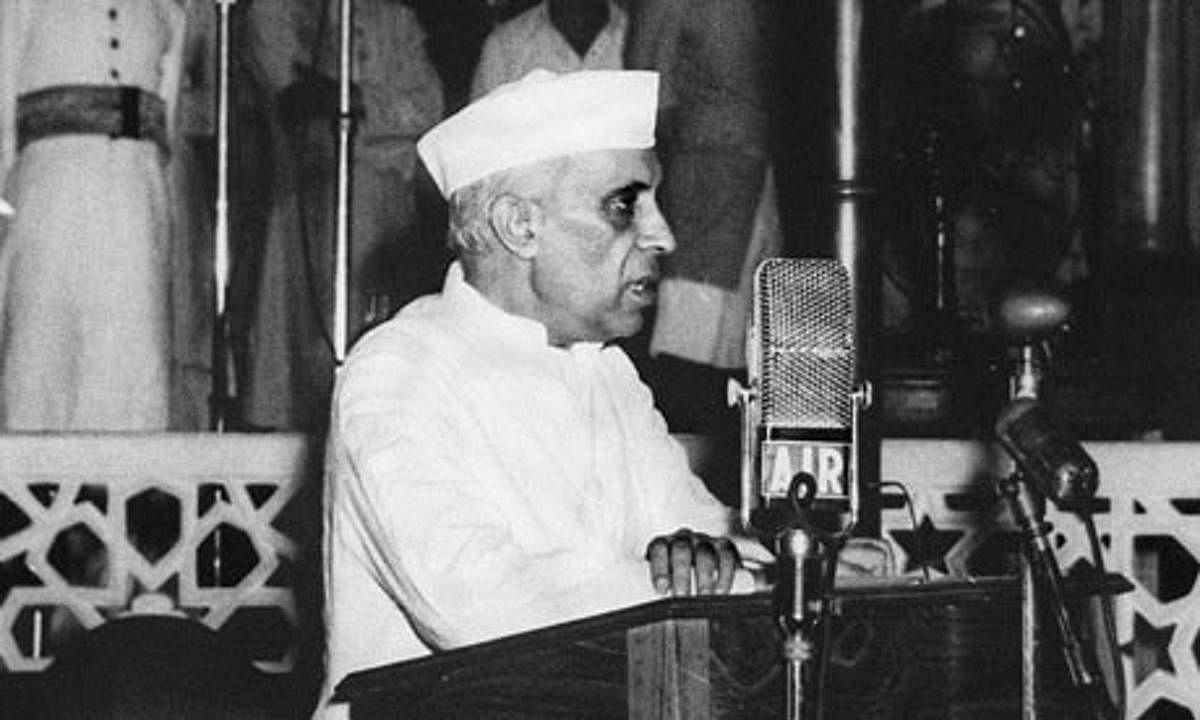

But let’s talk about what definitely were better times. In the 1950s and 1960s, when our Parliament was young and had stalwarts like Jawaharlal Nehru, Piloo Mody, Ram Manohar Lohia, et al, they were able to handle caustic comments and sharp-edged words with ease.

Lohia, the great socialist leader, would attack Nehru with violent wit, and the latter would counter with equally stinging words. Despite that, sessions were not disrupted because Lohia called Nehru a "bald man". Incidentally, that's ad hominem, since Nehru was bald.

Once, Lohia told the House that Nehru wasn’t an aristocrat as he was portrayed. “I can prove that the prime minister’s grandfather was a chaprasi in the Mughal court,” Lohia said. To which, Nehru smiled and replied: “I am glad the honourable member has, at last, accepted what I have been trying to tell him for so many years: That I am a man of the people.”

Not one Congressman rose up and screamed: “You called our leader a grandson of a chaprasi. Shame, shame” and caused disruption.

Nehru’s Finance Minister T T Krishnamachari once depicted Feroze Gandhi as Nehru's "lapdog". Feroze Gandhi didn’t take that lying down. He said since Krishnamachari considered himself a ‘pillar’ of the nation, he would do to him what a dog usually does to a pillar.

Congress' JC Jain once kept mocking Piloo Mody. An aggravated Mody yelled, “Stop barking!” Jain was up on his feet yelling and pleading with the chair: “Sir, he’s calling me a dog. This is unparliamentary language.”

Chairman Hidayatullah concurred and pronounced, “This will not go on record.” Piloo Mody corrected himself thus: “All right then, stop braying.” Jain did not know what the word implied. It stayed on the record.

On one occasion, Piloo Mody was censured for showing negligence to the seat by talking with his back to the Speaker. Mody shielded himself by saying, "Sir, I have neither front nor back, I am round." Such self-deprecating humour is the most effective instrument for managing tensions and keeping tempers cool.

In a parliamentary debate on the war with China in 1962, Nehru told Parliament that Aksai Chin, which the Chinese had occupied, was an area where “not a blade of grass grows.” Thereupon, Mahavir Tyagi, a senior Congress MP, pointed to his own bald pate and exclaimed: “Not a hair grows on my head. Does it mean it should be cut off and given to China, too?”

When Lohia was pleading for Stalin’s daughter Svetlana to be given asylum in India on the grounds of her marriage with an Indian, the charming lady member Tarkeshwari Sinha interjected to mock the bachelor Lohia as to how he could talk about conjugal sentiments when he didn’t have any experience of it. Lohia hit back: "Tarkeshwari, when did you give me any chance."

Once while rejecting an amendment moved by Rajaji, Nehru said: "You see, Rajaji, the majority is with me." Rajaji countered: "Yes, Jawaharlal, the majority is with you, but the logic is with me". Nehru laughed with the House, realised that Rajaji had a point and accepted his amendment. Such gestures are hardly conceivable now.

Speaker Somnath Chatterjee lost his cool when Varkala Radhakrishnan, a fellow communist, was going on and on with his speech, despite the Speaker telling him that the time allotted to him had expired. Chatterjee shouted from the chair: “Varkalaji, I know you have been a good Speaker, but you are a bad member.” Pat came the response from Varkala: “Sir, it is the opposite in your case. You have been a good member, but a bad Speaker.”

In contemporary India, tremendous changes have occurred in parliamentary proceedings. Most of the time of Parliament is being lost on political controversies, disorder and theatrics due to the passing of a controversial bill hurriedly or the refusal to permit a discussion on what the Opposition considers to be a crucial issue, or ignoring the Opposition’s demand to refer a matter to a committee for in-depth examination.

Nehru didn’t engage in political jousts with Sardar Patel. Ambedkar didn’t display a brisk no-nonsense manner with his colleagues. Though these great men, who shaped modern India, did have serious differences with their colleagues and opponents, the differences were argued out rationally, intellectually, and in civilised language. There was no personal vilification of each other. Arguments were always with the aim of convincing the other party, never with the aim of humiliating or disrespecting him/her. Of late, the fading away of wit and humour from the sacred temple of democracy is surprising since Indian literature and mythology, especially the indigenous cultures, are rich in humour and satire. The words spoken in Parliament are recorded for posterity. They provide an insight into the thinking of our elected representatives. They appear to be unable to lift the public discourse to the levels that a Nehru or a Lohia or an Ambedkar or a Vajpayee were able to. Listening to them, the public saw democracy as the path to a civilised society. Not any longer.

(The writer is retired Deputy Director of Boilers, Government of Karnataka)