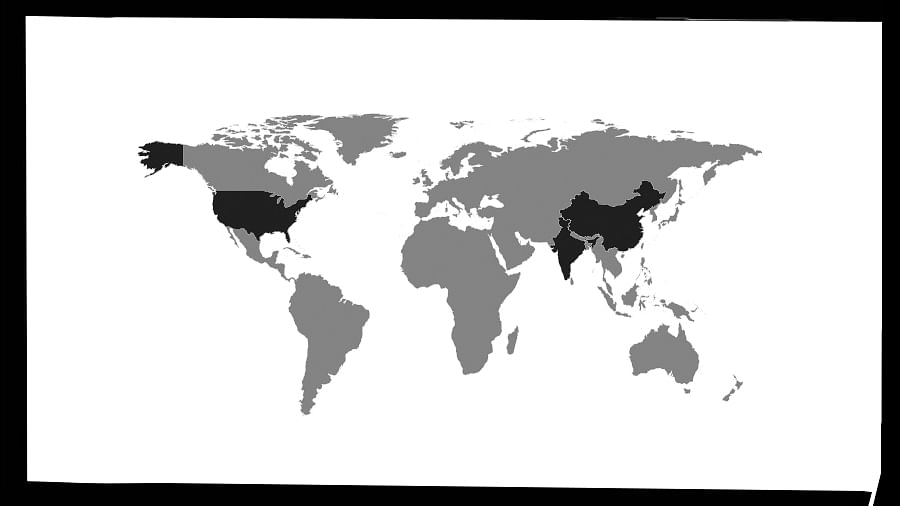

Credit: DH Illustration

It is impossible to read anything on geopolitics today without coming across the phrase ‘New World Order’. The narrative behind this rubric not long ago was that the liberal democratic world led by the United States was crumbling, this would throw up many uncertainties, and a likely result of this upheaval would be a Sino-centric world order. Such assumptions require deeper investigation; what constitutes a world order? How did the US reach the position of world leadership, and could China replicate this feat? And in what ways might India shape the existing or emerging world order?

The best definition of world order was perhaps made by Henry Kissinger, who died last week, as “the nature of just arrangements and distribution of power thought to be applicable to the entire world.” The two words ‘just’ and ‘power’ are crucial to this analysis; any world order should be based on a set of commonly accepted rules that prescribes the limits of permissible action, along with a balance of power that enforces restraint when rules collapse, preventing any one nation from subjugating others. A consensus on the legitimacy of existing arrangements would not foreclose competition and confrontation, but would contain them as adjustments within the existing order rather than as challenges to it.

While the existence of a State may often depend on its strength, achieving the status of a global player requires the attributes of both power and legitimacy. Power is the ability to impose one nation’s will over others, and such power is obtained through a combination of assets -- a strong military, favourable geography, a big economy, nuclear deterrence, soft power, and so on. But even the most powerful State requires another essential ingredient for world leadership, namely, the exercise of power that is deemed legitimate by colleagues and competitors.

Great Power status is the assertion of authority, an exercise of power that is not considered coercion but exercised legitimately. To strike this balance between power and legitimacy is the essence of statecraft because power without a moral dimension will degenerate into challenges or disagreements leading to tests of strength, when other countries are propelled into making calculations of self-interest amid the shifting configurations of power.

How nations have succeeded in becoming powerful is understood, but how they have attained legitimacy is less well-known. Since the international community is not governed by a single set of rules, leaders seek legitimacy by projecting their own values as superior to others, though there are critical distinctions between legitimacy, authority and power.

The rise of the US-led order is a pertinent example. By the end of World War II, the European powers, China and Japan were exhausted. The accumulation of power by the US was accompanied by the advocacy of liberty and democracy as values the international community was supposed to encourage, and the United Nations and a framework of multilateral institutions was constructed to reassure the world that the US was willing to place certain limits on its own authority. The western model of liberal democracy and free markets was promoted by widening the franchise and empowerment of women, though essentially it was practiced by only about 12 per cent of the global population. Nations that accepted this version of international order were granted the promise of security, economic assistance and technology transfer. These factors made the US the most powerful and the most authoritative State in the modern world.

However, the same factors might now be interpreted to indicate why this world order is dissolving despite the fact that there has been no diminution of the US’ power potential. There is widespread distrust of elected representatives and rising social and economic inequality in the West, and Washington’s conduct in recent decades has led to a perceived decline in its legitimacy. The states that tethered themselves closely to the US have dwindling confidence that they benefit from such an association, and the BRICS countries, along with some others like Turkey, believe they present an alternative model to western liberalism. Indian foreign minister Jaishankar, for example, was quoted in the Deccan Herald speaking of creating “international relations with Indian characteristics”.

The US has withdrawn from, or ceased to consistently support, many of the same multilateral arrangements that it helped to create, such as the Iran nuclear deal, Trans-Pacific Partnership, the International Criminal Court, Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, Law of the Sea, and many others. The emphasis of the Trump administration on ‘America First’, fair and equal trade, sharing the burden of common defence, and climate change denial added considerably to the perception of the US’ disengagement from world leadership.

As a candidate country that might replace the United States as world leader and setter of norms for a new world order, China requires scrutiny. China does not yet approach the US in power projection, but the Chinese Communist Party has declared its goal of world leadership. Nevertheless, Beijing has severe limitations which prevent China from exercising power with legitimacy.

The first is that the Chinese concept of world order is a reproduction of the Westphalian principles that preceded the rise of the US. Beyond the procedural aspects of non-interference in the internal affairs of other states and the inviolability of territorial integrity and sovereignty, this vision provides no new direction, and makes the assertion of legitimacy difficult. Secondly, even the multilateral institutions that China has developed are alternatives, rather than substitutes, for those created under post-WWII US leadership. Thirdly, China has no set of norms on which to build its own version of legitimacy, and its world view is constrained by an essentially hierarchical system that divides the world into the more and less sinicised. This is not appealing to most countries, and even if China eventually becomes the most powerful State, it will lack legitimacy and authority.

As for India, on many metrics of power potential, it is several rungs below China. But it possesses the civilisational attributes to contribute to a new international order attuned to contemporary realities. Its culture is innately cosmopolitan and embraces diversity and plurality, aspects that could be leveraged in shaping a world order that is humanity-centric -- the world is one family. The Indian Republic and its Constitution serve to show how a continent-sized multi-ethnic, multi-religious, liberal democracy can be constructed. The Indian narrative, therefore, has many aspects suitable for the generation of international legitimacy. But the challenge is to safeguard those values now under severe current stress, which could make it a legitimate world player upgrading to a world power while it adds to its hard power capabilities.

(Krishnan Srinivasan is a former Foreign Secretary. His latest book is Power, Legitimacy and World Order)