Sixteen, perhaps more, countries lodged protests over the controversial remarks on Prophet Mohammed by two BJP leaders. The government should be doubly chastened at these developments, not least because several of the protesting countries are theocratic States that have neither democracy nor freedoms that liberal democracies like India epitomise. Though ironic, how did this sorry state come to pass for a country like India that has centuries of the lived experience of pluralism? The recent events are symptomatic of growing dissatisfaction with a faith we ought to consider non-negotiable -- our faith in reason.

The reason is often referred to as transformative -- eulogised and invoked -- and as the means by which people can solve their problems and understand their worlds. Yet, in the discourse on religion in relation to politics in India, we need to ponder why it is that so many men and women, all applying reason to the same problems, find so many different answers.

Religion and politics are not siblings as the dominant political discourse across all parties in India has come to suggest, but wary strangers, in the manner in which they manifest in practice. Where should we draw the line of reason demarcating religion and politics -- blurred as it is today – without, at one extreme, surrendering all attempts to know and understand or, at the other extreme, becoming indistinguishable from the imputed zealotic or xenophobic? And if there is nowhere to draw the line, where does that leave us?

A good start would be to use reason to eschew unseemly language, the use of oxymorons, or writing and speaking against the grain merely to advance political interests or to win votes. Tragically, private agnosticism and public faith of much of the political class in the country have combined to reduce religion to serve as the handmaiden of politics. Communalism is born, as a result, from the constant preoccupation of a large proportion of Indians with the question of one’s religious identity.

The growth of such religion-based identity consciousness is resulting, in practice, in the creation of an oppositional other, and acting with full intention, in pursuit of conscious sectarian interests rather than the common good, characterising the profound change in India in the last 50 years. The quality and quantity of politics that this has produced, in more recent times, should constitute the specific context and cultural setting in which we need to reassess the current phenomenon of religious adversarial engagement, in particular the so-called Hindu revival, and its equally belligerent, fundamentalist Muslim and proselytising Christian response.

In practice, for all sides, this has meant the politics of sponsoring a religious group identity, loyalty, and commitment that proclaims its other as the exclusive opposition, and which pursues these divisions intentionally and politically. It creates images as well as symbols from the past and attempts to recreate and live a mythic reality -- of homogeneity and purity over place and time. It is political as much as, if not more than, anything else. Expressions like revivalist and fundamentalist are without any historical or epistemological grounding at all. They are essentially political in nature and serve contemporary political purposes.

The use exclusively of language like Sikh extremism, Muslim fundamentalism and Hindu supremacism or the general rubric ‘communalism’ in the dominant political discourse demonstrates that a way of seeing is also a way of not seeing. It distorts the contents of certain conflicts, suppressing the form that they bear in common with other confrontations based on oppositional dualities arising from exclusive identity-based consciousness; of caste, ethnicity, language, or region, for instance. It is a difference that makes the difference. In this miasma of hostility, tolerance is immediately conjured up as the magic wand; it has, in the religion of politics, acquired an aura of the only common sense, the sole solution. But it is dogma that does not work, regardless of whether it rests on enlightened equal respect of all religions (demanding a new ethical human being), or an enlightened equal disinterest (demanding a new rational human being).

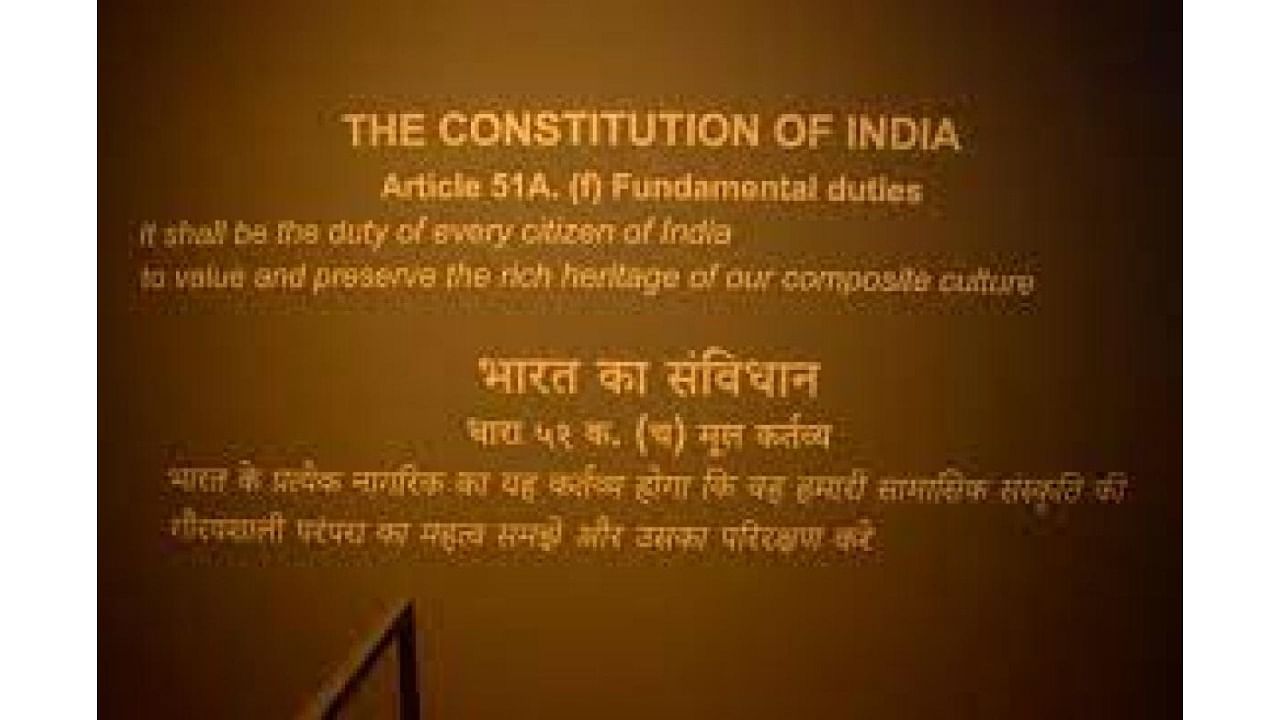

Under the circumstances, while there still lies a long road ahead toward a tolerant society, political practice and statecraft must, therefore, move decisively toward fulfilling the constitutional mandate in the matter: The State has no religion, and the State will not identify itself with and be controlled by any religion, and shall remain neutral as between different religions.

In this backdrop of the constitutional position, reiterated by the Supreme Court in various judgements, it is time that the political class, on the one hand, and the common citizen, on the other, recognise that all religious movements are essentially political, betraying the inability -- rather the unwillingness -- to sever religious faith from civil government. It is time to recognise that tolerance is not a position at all; it must be seen as the outcome of the absence of the need for any one final position.

To achieve this, though, we need to internalise a new understanding of the dynamic between the State and society in India; one that can serve as the striving for the future path that we consciously choose: Being Indian should not be seen as an alternative to being a Hindu, Muslim, Tamil, or a Tribal. It must not be seen, once again, as an either/or choice between the two; or that one or the other is superior. Rather, being an Indian should entail being all those other identities -- of religion, caste, class, region, language, gender. Such intersectionality must enable navigating multiple identities and loyalties, yet to be a prisoner to none.

We must restore our faith in reason as articulated in the Constitution, in our firm belief in the unequivocal separation of domains; and in the proper attributes to each: Politics and statecraft firmly in the public realm, and religion and its practice exclusively in the private realm. If we do, we might demonstrate to the world why we remain a plural society and a live democracy.

(The writer is Director, Public Affairs Centre, Bengaluru)