The wall between the Modi government and the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) has been getting thicker. The government had hoped it would collapse with Modi’s address to the nation on November 19, 2021, promising repeal of the three farm laws; it didn’t. It had hoped it would crash with their repeal by Parliament on November 29, 2021; it didn’t. It had hoped it would crumble with the announcement of a committee on MSP (minimum support price) on July 18, 2022; it didn’t.

The SKM refused to join the committee, saying it had ‘so-called’ farmers’ leaders who had openly backed the three farm laws. Ignoring the SKM’s absence, the committee is going ahead with its deliberations. It has already held three meetings. The SKM is going ahead with its agitation for legally guaranteed MSP. The committee is holding its meetings indoors; the SKM is holding its meetings on the streets.

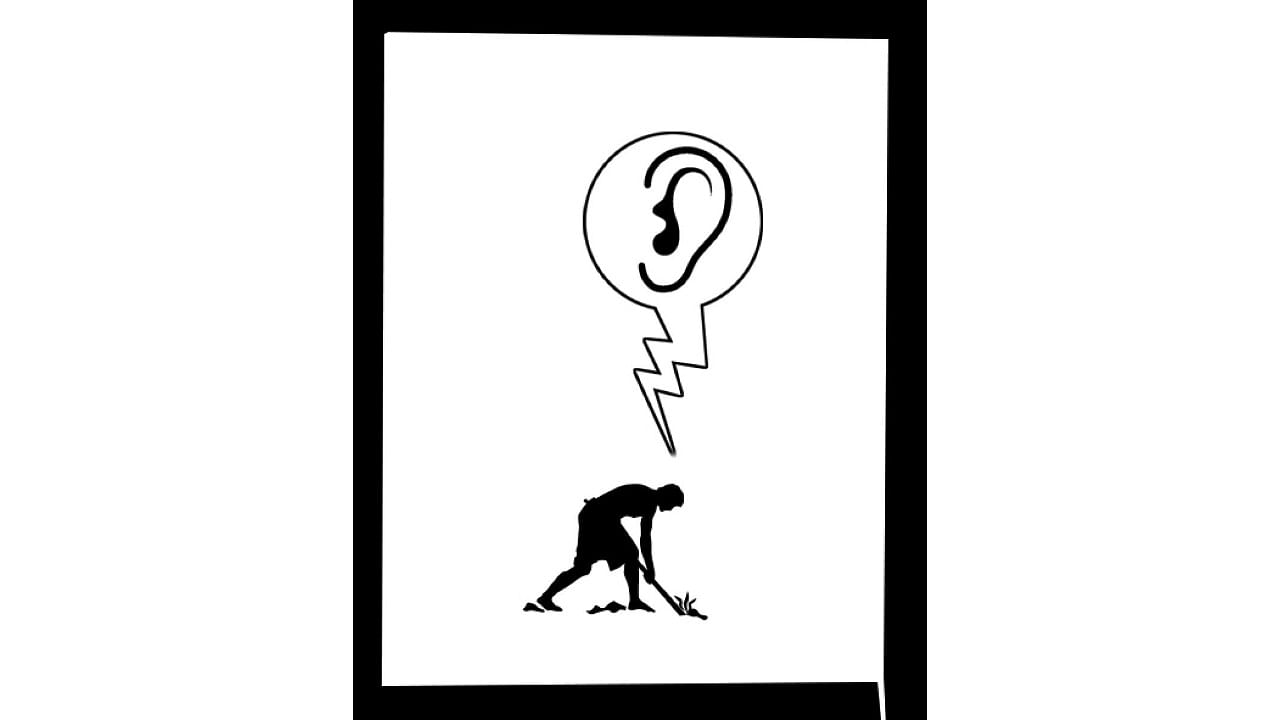

The absence of dialogue between the government and the SKM is not good for the country. The farmers are the backbone of agriculture. And agriculture is the backbone of the country’s economy. If the farmers suffer, agriculture will suffer; if agriculture suffers, the economy will suffer. Perhaps, due to the fact that there have been only minor setbacks to the BJP from the farmers’ movement in recent elections, the government doesn’t care much about their voice anymore. It is making a serious mistake. The farmers are the crew of the ship of agriculture. Unless they are on board, the ship will flounder.

The government is the management that sets the ship’s destination. It knows where the vessel has to go. Even the farmers, the crew, know where it has to go. The two only differ on how to reach there. The battle between the government and the SKM is convergence on the goal and divergence on the means.

Both the government’s and the farmers’ immediate big goal is crop diversification in the original ‘Green Revolution’ region—Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh. The farmers of the region abandoned other crops (millets, pulses, oilseeds) and started growing rice and wheat as the government lured them with assured procurement at assured prices, beginning in the 1960s. The rice-wheat cropping, particularly rice, sucked the upper aquifers dry. The farmers sank tubewells into lower aquifers to draw water, only to get metallic pollutants with it, which hindered generation of soil nutrients that were already in short supply due to the endless, Ghazni-like invasions by chemicals for higher yields.

The nation, tired of going around with a begging bowl, desperately wanted food security, and the farmers of Punjab, Haryana and western UP, motivated by assured income, helped achieve it. But a time came when both saw a nightmare eclipsing the fantasy. The yield stagnated, and with it the farmers’ income. Water threatened to soon become as elitist a commodity as silk, not just for irrigation but even for drinking.

In 2013-14, the central government introduced a crop diversification programme in Punjab, Haryana and western UP with the idea of moving farmers away from paddy to millets, pulses, oilseeds, vegetables and fruits, crops that do not beggar the aquifers or the soil. Crop diversification continues to be a programme of the central government. But in the past eight years, it has not made any significant progress.

In Haryana, paddy has been replaced with cotton in 20,000 hectares, which is merely 1.5 per cent of the total paddy area. In Punjab, whose soil anaemia is most severe among the three states, the programme has not taken off. Nor has it in UP.

The reason is obvious. The farmers are reluctant to switch to other crops. Their reluctance is founded on some pragmatic reasons. First, rice fetches them an assured sale with an assured income. Secondly, it brings higher income than other crops. According to official data, in 2018-19, a farmer in Punjab earned about Rs 75,000 from paddy, but only Rs 26,000 from potato, Rs 15,000 from maize and Rs 9,000 from gram per hectare.

Thirdly, though the government fixes MSP even for 21 crops other than rice and wheat—such as millets, pulses, oilseeds and cash crops—it does not procure them. Fourthly, the government, to fulfill its national food security aims, has over the years established a whole ecosystem—MSP, technologies, research, extension, procurement, processing—for paddy and wheat, which does not exist for other crops.

The government cannot motivate farmers to abandon paddy unless it is willing to establish secure ecosystems for alternative crops to help them earn higher incomes. Here lies the kernel of confrontation between the government and the SKM: the SKM wants the government to establish secure ecosystems, beginning with a legally guaranteed MSP. A guaranteed MSP means even private traders cannot pay the farmers less than that for their produce. If the farmers can expect an assured profit in other crops, they will take the road to diversification in increasing numbers.

The trouble with the ultra pro-‘reform’ Modi government is that it wants to minimise public spending on agriculture and open it up for the market. But with reduced public investment, you cannot establish secure ecosystems for crop diversification. There has not been as much research to develop high-yielding, pest-resistant and climate resilient varieties of pulses, oilseeds and millets as there has been of rice or wheat. You need funds for research. The type of soil in one village may differ from that in another; so, you need more extension workers to guide farmers in diversifying to other crops.

Public spending is needed to build a value chain for every alternative crop—from input supply to production to marketing to warehousing to processing—with incentives to private investment. It is only when the farmers see more profits in other crops that they will move away from rice. And more profits cannot come without a value chain.

It is in establishing value chains that the government must get the private sector involved. The government mistakenly tried to get the private sector involved in farming and trading through the three farm laws, which threatened the very existence of farmers. It must instead get the private sector involved in building value chains, where both the farmers and the market earn good profits. India cannot recast the nation’s food bowl without making both the farmers and the private investors happy.

(The writer is an independent journalist and the author of ‘Against the Few: Struggles of India’s Rural Poor’)