In the journey of human civilisation, cosmologies came to represent the distilled wisdom of humankind, accumulated over millennia in its quest for survival in the face of the adversities of nature and the basic human need to relate to fellow beings. Indeed, for thousands of years, cosmologies guided human thought and action concerning nature and the human and the non-human world. Western modernity sought to relegate “faith” to the footnote of history and bring the “scientific” to the centre of human affairs. In the ensuing turmoil, a great deal of wisdom lying in the grey areas of the cosmologies of non-Western societies was lost as the quest for, and the claims of, universal truths came to be associated with the binary of religion and science. Decolonisation saw cultural assertions in defence of indigeneity by the peoples of the colonies.

Tradition and revivalism constituted important elements of the Indian renaissance and nationalism, too. However, though present in the public sphere during our national movement, religion was not allowed to get in the way of the imagination of India as a humane, pluralist and inclusive society. The founding fathers of our Constitution gave us a secular, democratic republic in which people of all faiths would enjoy equal citizenship rights. It was an audacious experiment in arguably the most diverse society in the world. Nehruvian India celebrated the diversities of Indian society, and while reposing faith in science and technology as a vehicle of economic prosperity and well-being, the Indian State was guided by the principle of “neutrality” in respect of religion. Gradually, as political parties of all hues gave in to the lure of vote-bank politics, the State faltered in its commitment to secularism.

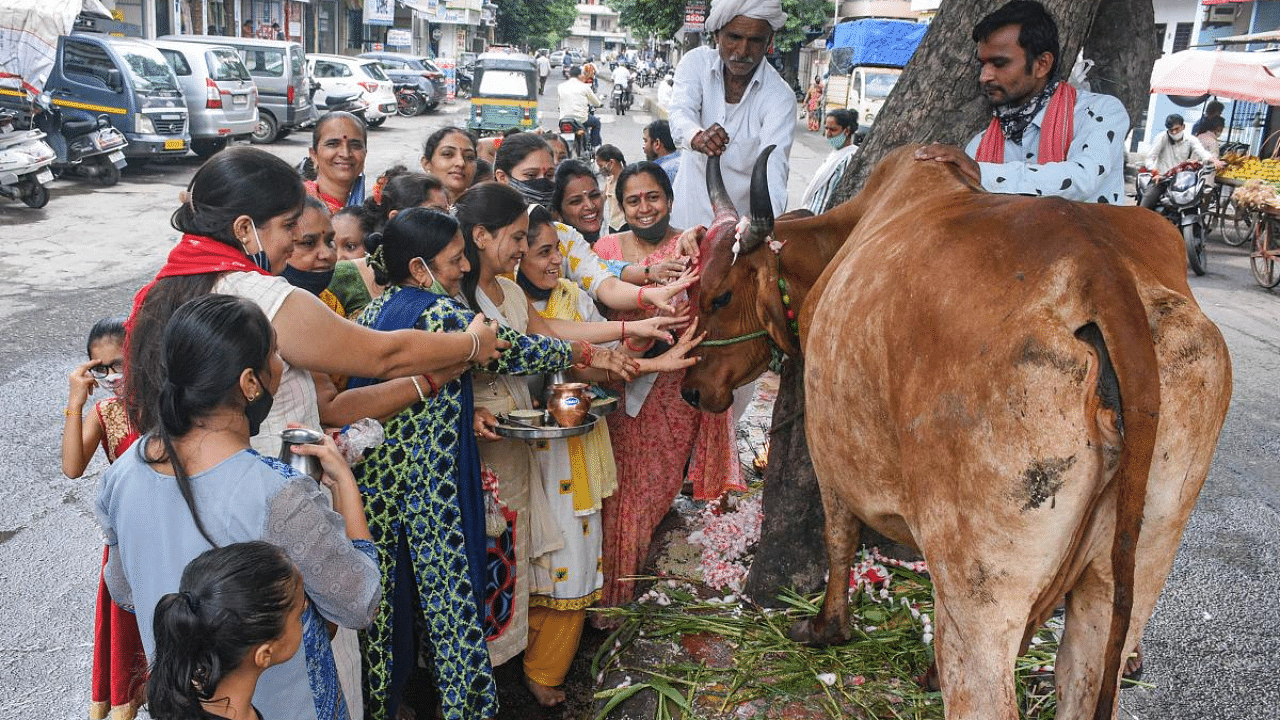

Religion and religiosity are on the rise in India, to the eclipse of constitutionally ordained secularism. The past few years have seen unprecedented brutalisation of our society in the name of religion and erosion of constitutional morality. Growing vigilantism has instilled a sense of insecurity and fear into the minds of the minorities. Ethnic majoritarian nationalism flattens diversities and others the minorities. In his recent book, Partitions of the Heart: Unmaking the Idea of India, human rights and peace worker Harsh Mander has meticulously documented communal polarisation taking place first in the society of Gujarat in the wake of the Godhra incident in 2002 and then its replication in the rest of India since 2014. He feels fraternity, our most cherished constitutional value, is being irremediably corroded in India of today.

Based on massive global survey data, Ronald F Inglehart, in his book, Religion’s Sudden Decline, has argued that since 2007, the world is generally becoming less religious. India is an exception in this survey, where religiosity increased markedly. The Pew Research Centre’s latest survey, Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation, confirms this trend. Several commentators have interpreted the findings of the survey. They seem to agree that the findings hint at a marked rise in majoritarian tendencies in India and, thus, lend credence to the tide of Hindutva. Our leaders’ growing display of religiosity in the public sphere of today’s India seems to be in sync with the finding that 64% of the Hindus in the Pew survey thought that “politicians should have a large or some influence in religious matters.”

Hindu nationalism attempts to blend religion and science to secure India’s rightful place in the comity of nations; domestically, its goal is to establish the supremacy of Hindu religion and culture, and ultimately a Hindu Rashtra in India.

This blending of religion and science finds expression in wild and bizarre claims made about scientific and technological progress made in ancient India and in imputing scientific significance to narratives found in our folklore and mythologies. Our political leaders have speculated on the prevalence of genetic science and stem cell research and the significant advancement of science and technology in ancient India.

In a remarkable interdisciplinary study, Holy Science: The Biopolitics of Hindu Nationalism, Banu Subramaniam has argued that contemporary India envisions alternative modernity by bringing “together a melding of science and religion, the ancient and the modern, the past and the present into a powerful brand of nationalism.” This, she terms, archaic modernity. While Subramaniam celebrates the progressive possibilities that the convergence of science and religion may offer, she is emphatic in her rejection of the ends that the project of Hindu nationalism seeks to attain by blending science with religion – that is, the supremacy of Hindu religion and culture.

Recently, prominent industrialist and philanthropist Azim Premji appealed to fight the Covid-19 pandemic with good science and truth. He said: “At the core of the idea of good science is the matter of being willing to accept and confront the truth…Science and truth are the foundation on which we can tackle this crisis and ensure that it is not repeated,” he said, “Together we are stronger, divided we continue to struggle…we need to restructure our society and economy such that our country does not have this kind of inequity and injustice.”

We are not sure whether Premji was endorsing the universal truth claims of modernity. However, besides science, Premji also highlights the importance of togetherness and the need to restructure our society and economy to fight inequity and injustice, which primarily pertains to politics.

The question that stares us in the face is: Does the nature of prevailing politics allow, if not actively promote, the practice of good science and good religion in our society?

Science and religion must come together in the project of the creation of a compassionate man and a compassionate society. No religion is good unless it dispels unreason, brings people together, and ushers in an era of peace and goodwill. And no science is good unless anchored in a higher moral purpose and is helpful in leading a lifestyle that is in harmony with nature.

(The writer is Adjunct Faculty, Department of Social Sciences, FLAME University, Pune)

Watch the latest DH Videos here: