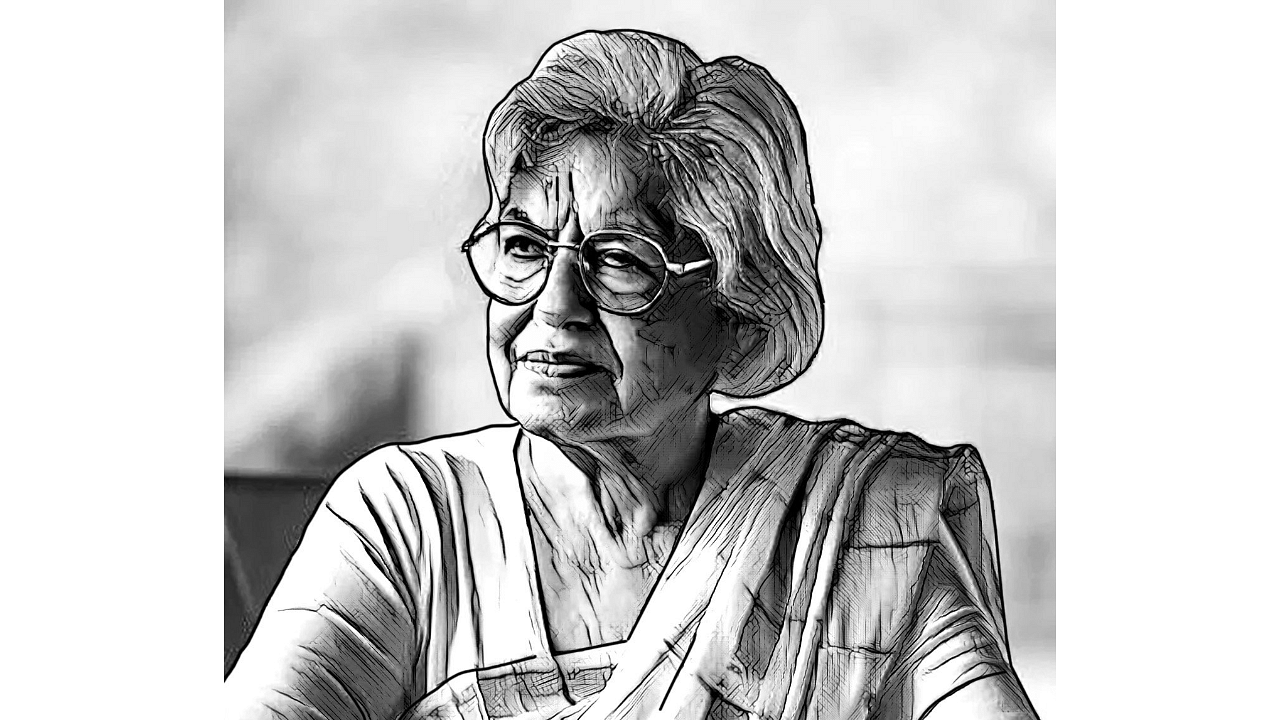

Indira Jaising is a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India and a noted human rights lawyer

The most beautiful and satisfying parts of the Constitution of India are to be found in the Preamble which captures the vision of India, defining its foundational values – socialism, secularism, justice, liberty, equality and fraternity. Its social and economic content is to be found in the Directive Principles of State Policy which are not binding but are, nevertheless, fundamental to governance.

These principles focus on re-distribution of the country’s material resources so as to best subserve the common good, principles such as equal pay for equal work for man and woman, fair wages for work, and protection of the marginalised sections of society.

It is unfortunate that these principles were made unenforceable. This was, perhaps, on the understanding that the country did not yet have the resources to make social and economic rights immediately enforceable, but they could be progressively enforced by the State. Over the years, the Supreme Court’s effort has been to interpret our fundamental rights in the context of the Directive Principles. It is under the right to life and liberty that our courts evolved a method of implementing several social and economic rights.

During the formulation of the Constitution, there was focus on the abolition of the Zamindari system and land distribution which was challenged based on the right to property, a fundamental right. Ultimately, the right to property was deleted from the chapter on Fundamental Rights and made a Constitutional Right. It was in the Kesavananda Bharati case (1972) that the Court gave the seminal judgement that Parliament could not amend the basic features of the Constitution – democracy, equality, liberty, federalism and secularism. The judgement continues to stand between Parliament and any attempt to abolish some of these foundational principles.

The early years did not see a robust defense of the right to life and liberty. It was only later, in Maneka Gandhi (1978), that the Court moved the compass to defend rights in favour of due process.

As a practising woman lawyer, when I look at the Constitution, the first question I ask myself is – “What does the Constitution have to offer women?” The quick answer is: non-discrimination based on sex. This was the contribution made by B R Ambedkar. Article 15 (1) reads: “The state shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them”. This was my theory of liberation as a woman, and as a professional. Yet, to my horror, I found that the air hostesses of Air India who came to me for legal advice were being told that they had to retire on having children. They could also never become supervisors on board an aircraft. Air India was, at that time, a public sector airline.

The Constitution had a poor beginning when it came to women in the Court’s early years. This injustice was noted later and the Court

shifted from a formalistic understanding of equality to a substantive understanding of equality for women. Subsequent judgements reflect this shift – from Vishaka (1997) which laid the foundation for preventing sexual harassment at workplaces to the Indian Young Lawyers Association (2018) which struck down a rule that prevented women aged between 10 and 50 from entering the Sabarimala temple.

The journey for reservations of SC and ST in public employment has been traumatic. There was always resistance by the upper castes to the very idea of reservation. The jurisprudence of the Court failed to reflect the base of reservations which was untouchability. This left the door open for the upper castes to demand reservations which they finally did on behalf of the Economically Weaker Sections, in Janhit Abhiyan (2022). On the other hand, the implementation of the constitutional promise of representation in organs of state power remains dependent on political considerations.

This brings me to the country’s record in secularism. We have witnessed a severe erosion of the principles contained in the Preamble, primarily of secularism. Public discourse by the ruling party at the Centre is openly hostile to minorities and this reflects in their policies and practices. Criminal law has become the primary tool of governance. This has created an atmosphere of fear among the Opposition parties and civil society activists who stand up to the politics of Hindutva. In this respect, democracy as we know it – as a system of adult franchise for selecting our representatives – has failed us.

It is difficult to evaluate the legacy of the Constitution over 75 years in a short column. We, however, can try tracing it through the legacy of the Court – conservative to begin with, swinging towards protecting social and economic rights at its midpoint and now, on a downward curve when it comes to our civil and political rights.

Yet, we can look forward to the next 25 years as years for reclaiming the vision of the Constitution. Also, perhaps, for deepening our rights framework and entrenching more fundamental rights. n

B R Ambedkar noted that the Constitution of India was not a mere lawyers’ document – “It is a vehicle of life and its spirit is always the spirit of age.” Seventy-five years since the adoption of the Constitution, its living text continues to guide India along the vision of its founders. But these are also times when the constitutional spirit is increasingly in conflict with reactionary narratives that undermine the tenets of the document. The Prism looks at the milestone with a throwback to the Constitution’s framing principles, nods to its endurance, and underlines threats to its foundational ideas.