About 25 years ago, when Professor Suhas Sukhatme had just completed his term as director of the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, his interview was published in a national daily. One of the questions he was asked was what were some of the highlights of his five-year tenure as director. He promptly gave a one-line answer, “Nobody called me to seek admission for their ward”. This answer has deep significance.

Firstly, it shows that you can’t get admission by influencing the director. Secondly nobody in the ‘system’ even thinks of calling and using influence. Whether it is ministers, industrialists, politicians or elites, getting IIT admission by any other means apart from an entrance exam was unthinkable.

This was simply an unwritten rule, or a norm, that had been implicitly codified over the years. And everyone abided by it. This norm endured because of the trust in the sanctity of the joint entrance exam, and because its integrity was inviolate. In fact, other institutions such as the regional engineering colleges piggy-backed their admission systems on the JEE ranking because of its integrity. Such a system lasted for about four decades when there were only five IITs, and the number of admissions as well as applicants was manageable, and the exam was administered end-to-end by the IITs themselves by rotation.

Successive generations of IIT faculty ensured that the sacred norm was sustained, and integrity was not compromised. But that did not last. The gap between supply and demand widened.

The premium of getting into IIT zoomed sky-high. The coaching class industry made out like bandits. This called for an increase in seat supply. Eventually, the number of IITs proliferated, admissions increased, and applicant numbers zoomed.

Around 2013, there was intense policy discussion about introducing ‘one nation, one test’ for all the major engineering and medical seats in India. The motivation was to reduce the hassle for students and parents of running from pillar to post, appearing for multiple entrance exams. It was also to create a uniform standard across the country. There was grave concern about the non-level playing field created by the coaching class industry, and the huge profits that they were skimming.

So finally, we did switch over to the ‘one test’ model, with the JEE being split into two stages. A separate agency was set up in 2017, called the National Testing Agency, and now the NTA is in charge of conducting the four big exams, namely: the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET) the gateway to medical seats, the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) for engineering seats, the University Grants Commission National Eligibility Test (UGC-NET) and the Common University Entrance Test (CUET). The experience of the last few years has not been without hiccups for all these tests.

These have led to great anxiety for students and parents. Not to forget the Kota suicides phenomenon related to the inhuman stress on those preparing for the competitive exams, whether JEE or NEET.

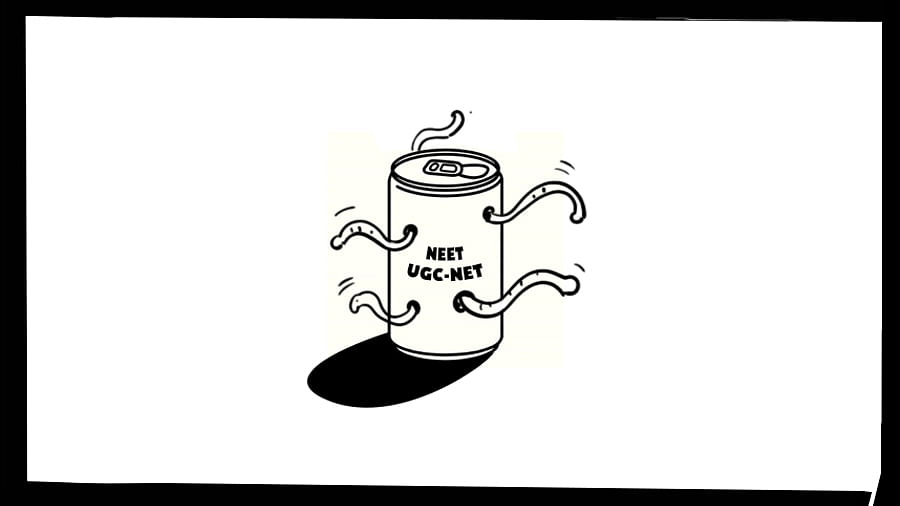

This year there is a major controversy about two of the big exams, NEET (undergraduate) and UGC-NET. The latter was scheduled for June 19 and abruptly cancelled with barely one day’s notice.

About 0.9 million students across 317 cities were to appear for this exam. The NTA cancelled it because it was concerned about paper leaks.

This cancellation came days after the still raging controversy on the NEET-UG whose results were announced on June 4, the same day as the results of the Lok Sabha elections.

This exam was taken by 2.4 million students across 571 cities and 4,750 centres. But the results seemed absurd. Marks which would have got a rank around 6,800 last year, got a rank of 21,000. Or marks ranked around 28,000 now ranked beyond 80,000. Besides, 67 students got a perfect score, with six of these in the same sequence, from the same centre. All this created a lot of disquiet.

When scores were shared by parents and applicants on social media, another very unusual phenomenon was discovered, which had not been disclosed by the NTA. That 1,563 students had received grace marks for which no prior condition had been announced. Grace marks can be given to students with a disability for certain reasons, but in this case, they were given because the question papers arrived very late.

By now everything has landed in the Supreme Court. The grace marks have been cancelled, and a retest ordered. But the question remains whether such a benefit should have been made available to all, and not a select few only.

This seems unfair. What about the suspicion of mass leaks, and compromising of the NTA’s exam machinery? There seems to be a big cheating scam, and some arrests have been made in Bihar and Gujarat. The saga is not over, nor is the untold stress for students and parents.

This fiasco calls for a massive overhaul and reforms. Tests which use Optical Marks Recognition (OMR) require printing, transporting sealed packages, and ensuring tamper-proof packaging. Such a system is obsolete. Indeed, a prominent government-owned testing agency in Maharashtra, migrated to a screen-based system almost 15 years ago.

With tools like AI, and live proctoring software, we don’t need to use OMR with the attendant risks. The software and AI basis allows dynamic and randomised sequencing, and even paper setters will not know the full exam until it is administered. These are tech-based solutions, which are tried and tested, and used in many places across India.

Secondly, we must find ways to reduce the excessive premium on one exam, and one national testing body. Either have multiple (at least two) competing standards (for tests), or allow a few private players. Let them compete based on reputation, rigour, and integrity.

The third long-term reform is to reduce the massive demand-supply gap, by working on both sides of the equation. This also means unshackling the education sector, allowing greater freedom and autonomy to institutions of higher education, in deciding curricula, courses, faculty hiring and salaries, student fees, and programmes. Otherwise, millions of Indians are wasting the prime years of their youth with a psychological burden, and gruelling study with repeated attempts, to crack exams, where the odds of winning are worse than a lottery.

(The writer is a Pune-based economist) (Syndicate: The Billion Press)