Credit: DH Illustration/Deepak Harichandan

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has recently imposed a Rs 1 crore penalty on HDFC Bank for violating guidelines related to the practices of recovery agents. These agents were found to have contacted customers in ways that invaded their privacy and caused considerable inconvenience. The bank was also found in violation of directives concerning ‘Interest Rate on Deposits’. The world beyond the licensed banking system is even murkier and more grim.

Every day, newspapers are full of disturbing stories of harassment and threats by loan recovery agents, forcing many into despair -- some tragically to the point of suicide.

Bhupendra, a resident of Bhopal, took a final selfie with his family before poisoning his two sons, aged eight and three. He and his wife then hanged themselves. In a four-page suicide note, he mentioned being trapped in the loan app cycle. He explained that recovery agents had tortured him for months. Their final message from them was: “Tell him to repay the loan; otherwise, today I will strip him naked and upload it on social media.” This tipped him over the edge, driving him to end his life and that of his family. The incident occurred in 2023.

Pratyusha, a resident of Chinnakakani village in Guntur district, Telangana, had borrowed Rs 20,000 from a loan app to tide over a momentary crisis. Even after repaying several instalments, the exorbitant interest rates made it impossible for her to clear the debt. Meanwhile, loan recovery agents began harassing her, even threatening to post her morphed nude pictures online and send them to her relatives. Before committing suicide, Pratyusha narrated the entire ordeal in a recording. Even after her death, loan app representatives continued to harass her relatives over the phone. This incident took place in 2022.

Another case from 2022 that shook the nation was from Jharkhand. Monica Mahato’s father, a resident of Hazaribagh, had taken a loan from a finance company to buy a tractor. He was supposed to repay the loan in 44 instalments. The father said he had six instalments left when the pandemic wrecked havoc. The recovery agents of the NBFC barged in and forcibly seized his tractor. Monica tried to block them by standing in front of the tractor but was crushed to death. At the time, Monica was pregnant.

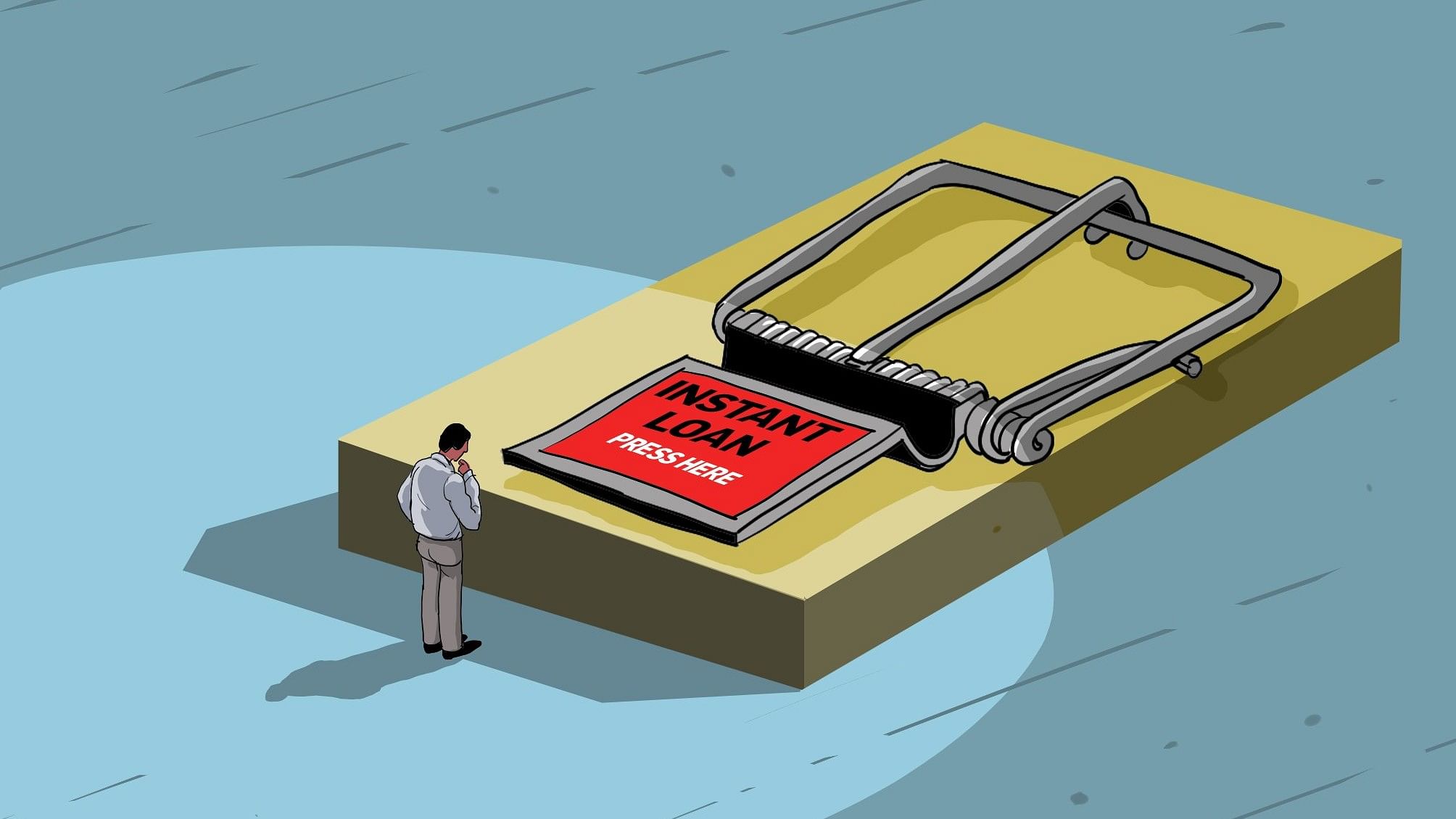

These modern-day moneylenders, including non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs) and an entire ecosystem of easy loan apps, have mushroomed across the financial landscape of the country over the last decade, preying on those ignored by the formal banking sector. While they provide services similar to banks, they are not actual banks and do not hold full banking licenses. They specialise in offering instant home loans or car loans with minimal documentation and within a short time frame. Their dominance is particularly evident in rural areas, where established banks are scarce, and they primarily target marginalised sections of society. However, as the cases above illustrate, they are notorious for their high interest rates, short repayment periods, and inhumane recovery agents.

Once a payment is missed, recovery agents begin publicly shaming the borrower, issuing threats over the phone, and humiliating them in front of neighbours and relatives, often pushing them toward extreme steps. From threatening legal action to using obscene language, they leave no stone unturned. They even illegally access borrowers’ phone books, harassing family members and colleagues. They don’t hesitate to morph photos from the borrower’s gallery or social media and use them for explicit content, which often leads to suicides or severe mental stress.

Such harassment saw a sharp increase after the pandemic. Complaints about digital lending received by SaveThem India Foundation, for instance, increased from 29,000 to 76,000 between 2020 and 2021. According to the latest National Crime Records Bureau’s report, there was nearly a 25 per cent increase in registered cybercrime cases between 2021 and 2022, and about 65 per cent of the cybercrime cases registered were for the motive of fraud (42,710 out of 65,893 cases).

A survey conducted by LocalCircle from July 2020 to June 2022 showed that 14 per cent of surveyed Indians utilised instant loan applications. While this has come down to 9 per cent in the latest survey, those encountering exorbitant interest rates still remain worryingly high. Forty-five percent of users said that the rate of interest charged was over 25 per cent per annum; 10 per cent got it at a 50-100 per cent interest rate; and 20 per cent at a higher interest rate of 100-200 per cent.

The latest survey also found 61 per cent complaining about extortion threats or data misuse. Former general secretary of the All India Bank Officers’ Confederation, Thomas Franco, also warned that if public banks do not expand their presence, India’s poor and unorganised sectors will remain dependent on NBFCs, micro-finance institutions (MFIs), and unreliable loan apps, resulting in rising suicide rates.

However, NBFCs are still seen as playing a crucial role in making loans easily accessible to marginalised citizens. Therefore, the NBFC ecosystem has received active encouragement from policymakers over the past few years. Banks have been directed to provide adequate funds to NBFCs to help them expand their operations. In an attempt to make the microfinance terrain a level playing field for all, the RBI’s new framework in 2022 has meant that the market share of banks has reduced considerably, while that of NBFC-MFIs has grown to claim the top spot.

NABARD’s Status of Microfinance in India 2023-24 shows that banks are losing ground as their share in total loans outstanding fell from 43.67 per cent to 32.53 per cent during 2020-21 to 2023-24, which has been taken over by NBFC-MFIs and Small Finance Banks. During FY 2024, all MFIs collectively mobilised Rs 91,789 crore, of which the share of NBFC-MFIs and NBFCs constitutes 97 per cent. The RBI has also removed the cap on interest rates charged by NBFCs, allowing them to lend to small and rural borrowers at exorbitant rates.

Too little, too late?

The RBI has on multiple occasions recently expressed its concern about the usurious interest rates charged by NBFCs, the non-transparent methods to calculate interest, and the harsh recovery practices deployed by them. RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das has issued warnings, stating that NBFCs must not misuse the regulatory freedom they have been given in setting interest rates. Very recently, it has, for instance, imposed a monetary penalty of Rs 10,40,000 on Hewlett Packard Financial Services (India) Private Limited for non-compliance with certain provisions. This includes their failure to disclose and explicitly communicate the rationale behind differential rates of interest to borrowers. The RBI has also cancelled several NBFCs’ licenses and witnessed others exit the market, underscoring the volatility of the NBFC ecosystem.

NABARD in its latest report has warned that “the significant presence of lenders and removal of caps on lenders have led to some pockets of indebtedness” that need close monitoring. It also stressed the need to ensure that “interest rates to clients, which are now deregulated, are within acceptable limits.”

Noting the need for “striking a balance between expanding outreach and responsible lending,” it recommended robust credit assessment processes for NBFC-MFIs that specialise in microfinance. It also spoke of our poor track record in meeting global standards on responsible digital finance developed to ensure client data is protected and that there are checks and balances in place to prevent fraud, among other risks.

But in the context of the overall celebratory tone around “financial inclusion” and favourable policy prescriptions, the occasional warnings or expressions of concern by the RBI and NABARD about NBFCs seem rather perfunctory. There seems to be no effective remedy against these loan sharks. Given that the SC’s directives have made state governments powerless to regulate NBFCs, the task of curbing this loan trap and reining in the recovery agents and interest rates of the NBFCs lies with the central government. If it fails, there is a growing concern that as economic distress deepens, more people will be driven to suicide owing to over-indebtedness and the vicious loan trap.

(The writer is with the Centre for Financial Accountability, New Delhi)