The Supreme Court judgement of November 7 in the Janhit Abhiyan v Union of India case which upheld the constitutional validity of the law granting 10% reservation to Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) among the unreserved category effectively delinked reservations from caste and placed the individual, defined by economic status, at the centre of the reservation scheme.

The 103rd Amendment of the Constitution thus made a departure from the normative reservation scheme which was based on group identity, and the endorsement of this departure by the court will have important consequences for the idea and practice of reservation in the country.

The idea of reservation and the judicial decisions on it have a chequered history. While the practice of reservations was started by some progressive princely states even before Independence, the idea of it for a free nation grew out of the 1932 Poona Pact between Gandhiji and Babasaheb Ambedkar, which gave representation to Dalits within the Hindu electorate, but went through many changes later.

It received legal and constitutional sanction through the First Amendment of 1951, which empowered the State to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and economically backward classes, specifically Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) and, later, Other Backward Classes (OBC), through reservation in education and government jobs. A number of judicial decisions in later years clarified the reservation idea, expanded it, built on it and sometimes limited it, and some of those decisions have not agreed with one another.

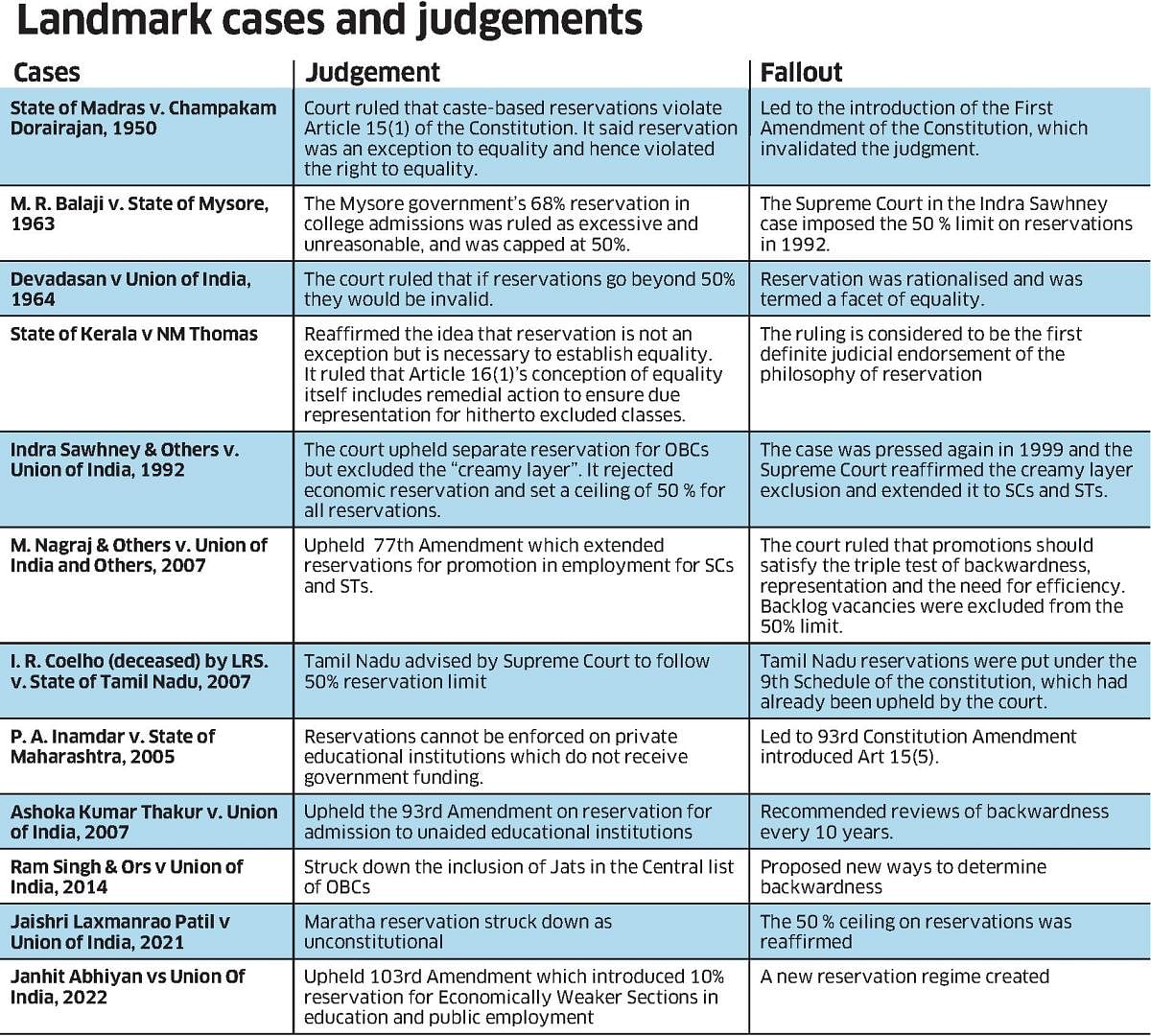

The First Amendment was itself a response to a decision of the Supreme Court in the Champakam Dorairajan case of 1950 in which the court ruled that reservation was an exception to equality and hence violative of the equality concept envisaged in Part III of the Constitution. That led to the amendment of Article 15 and others, giving constitutional backing for the idea of reservation for socially and economically backward classes. Later, through the Devadasan case of 1964 and the N M Thomas case of 1975, the court’s view evolved to one that saw reservation not as an exception but as a facet of equality.

This idea of reservation has been weakened by the court’s latest judgement. By a 3:2 majority, the court upheld the validity of the 103rd Amendment and ruled that the EWS quota did not violate the basic structure of the Constitution.

The then Chief Justice of India U U Lalit and Justice Ravindra Bhat, however, dissented from the majority view of Justices Dinesh Maheshwari, Bela Trivedi and J B Pardiwala and held that the Amendment must be struck down as it is discriminatory. It is discriminatory because the EWS quota, although based solely on economic criteria, excludes the SC/ST/OBCs and is meant only for those who did not benefit from the existing reservation system –

that is, it is meant only for the upper or forward castes.

The conclusion of the bench that reservation made on exclusively economic grounds is valid goes against the political, social and constitutional ground for reservation as it was originally conceived and has held good till now.

The rationale for reservation is that the historically marginalised groups who have suffered from social and economic backwardness need special accommodation from the State and representation in it. It is a means to achieve substantive equality in an unequal society and has been seen as a measure for reparation. That is why a nine-judge bench of the court in the Indra Sawhney case in 1992, which upheld reservation for the OBCs, held that economic status alone cannot be a criterion for reservation. The five-judge bench has now gone against that view and validated such economic reservation, aimed solely at EWS.

The Janhit Abhiyan judgement has also allowed reservations to breach the ceiling of 50% set by the court in the Indra Sawhney case and reiterated in many later judgements. The argument that the ceiling applies to only caste-based reservations opens a Pandora’s box. Once the ceiling is breached for any reason, it can be breached again and again, and the considerations for doing so will be, as is the case with EWS reservations, political, and will not be guided by the principle of social justice or by public interest.

Discriminatory Provision

The biggest infirmity of the 103rd Amendment is that it excludes from its scope a large class of people who are eligible for reservation under it by virtue of their economic status just because they belong to groups that are entitled to caste-based reservations. There may be some political logic for it, but it has no legal and constitutional rationale. It is an arbitrary decision and amounts to denial of the right to equal opportunity, which is a fundamental right, to a large section of people. The logic that a person cannot get one benefit because he or she is getting another one is not right and legal.

The majority judgement has justified this discrimination on the basis of “reasonable classification”. “If the economic criteria based on the economic indicator which distinguishes between one individual and another is relevant for the purpose of classification and grant of benefit of reservation under clause (6) of Article 15,” wrote Justice Pardiwala, “…then merely because the SC/ST/OBCs are excluded from the same, by itself, will not make the classification arbitrary and the amendment violative of the basic structure of the Constitution.”

But those who have been entitled to reservation till now to correct for historical injustices they suffered and the others who have been offered the facility based on their current economic status are equal before the Constitution, and they should not be treated differently. That is why the denial of the EWS reservation to SC/ST/OBC segments is discriminatory and falls foul of the Constitution. Justice Bhat, in his dissent, said that SC/ST/OBC reservations are not a “free pass” but a “reparative and compensatory mechanism”. The inclusion of the forward castes and exclusion of the disadvantaged castes, who suffer from social and educational backwardness, from the ambit of EWS reservation militates against Article 14 which guarantees equality before law. This unequal treatment of equal citizens is anathema to the basic structure of the Constitution.

Arbitrary Quota, Criteria

There are other questions, too. Why was the EWS quota fixed at 10%? Why not 9% or 11%? Is it because 9% would look too little and 11% would look too big? In the absence of any data to support it, the quota has been arrived at arbitrarily. There are practical issues at the level of implementation, too. The income limit to be eligible for EWS reservation is Rs 8 lakh per annum, which is about Rs 2,200 per day. Can households with that level of income be considered “economically weak” in a country where Income Tax kicks in at Rs 3 lakh per annum income level? In a country where any certificate can be bought, would it be difficult to buy a place in the EWS segment?

It should be noted that the EWS reservation is actually directed not at the EWS segment as a whole but at the individuals who may belong to that segment. No-one can benefit from it just because he or she belongs to a group whose definition would keep changing. This year’s beneficiary may not remain a beneficiary next year because the economic status of individuals can change. Potential beneficiaries will have to prove themselves eligible for it time and again. Should an entire reservation system, which involves setting apart and utilisation of public resources, be aimed at individuals? Reservations are meant for communities, and not for distressed individuals.

Moreover, poor economic status is often the result of uneven distribution of resources, and it is the economic policies of governments that aggravate poverty and widen the rich-poor gap. Should State resources be spent institutionally and exclusively to ameliorate the situation of some of them? Reservation was not meant to be a poverty alleviation programme or a welfare scheme.

The existing beneficiaries of reservation are doubly disadvantaged. They are socially and educationally backward and economically distressed due to historical reasons. Reservations for them necessarily involve both redistribution and representation. The poor among the forward castes are singly disadvantaged. They can be assisted with appropriate policies for redistribution and affirmative action. Extending reservations to them delegitimises the idea of reservation. The need for distributive justice should not be mixed up with the policy of representation through reservation.

Seed of destruction

The EWS quota idea also contains within it the logic and the seed for dismantling the entire reservation system. Two comments from the majority verdict are worth noting. Justice Bela Trivedi held that “we need to revisit the system of reservation in the larger interest of society as a whole, as a step forward towards transformative constitutionalism”. Justice Pardiwala said that “reservation should not be allowed to become a vested interest…as larger percentages of backward class members attain acceptable standards of education and employment, they should be removed from the backward categories”.

The elite logic for overhauling the reservation system can thus easily, if self-servingly, run like this: If economic reservation is legal and constitutional, why not extend that to all people and do away with the conventional reservation scheme? A ‘one nation, one reservation policy’, so to say! A pious sentiment can also be put forth that people should not be defined by their castes and the attempt should be to move to a casteless society, and that caste-based reservation had to be phased out anyway. Economic reservation can be defined in such a way that all those who need reservation will get it and those who do not need or deserve it can be excluded. These arguments may sound right and reasonable in the environment that is taking hold in the country and can be used to dilute or do away with the existing system of reservations.

All one has to do is conveniently ignore the fact of historical oppression and suppression of the backward castes and how that has, over centuries, disadvantaged them with respect to the caste elites.

The judgement certainly needs to be reviewed.

(The writer is a former Associate Editor and Editorial Adviser of Deccan Herald)