"Whatever action is performed by a leader, common men follow in his footsteps…It does not behove leaders to indulge in acts or speeches that cause rifts amongst communities…Hate speeches by elected representatives…militate against…fraternity, bulldoze the Constitutional ethos…’’

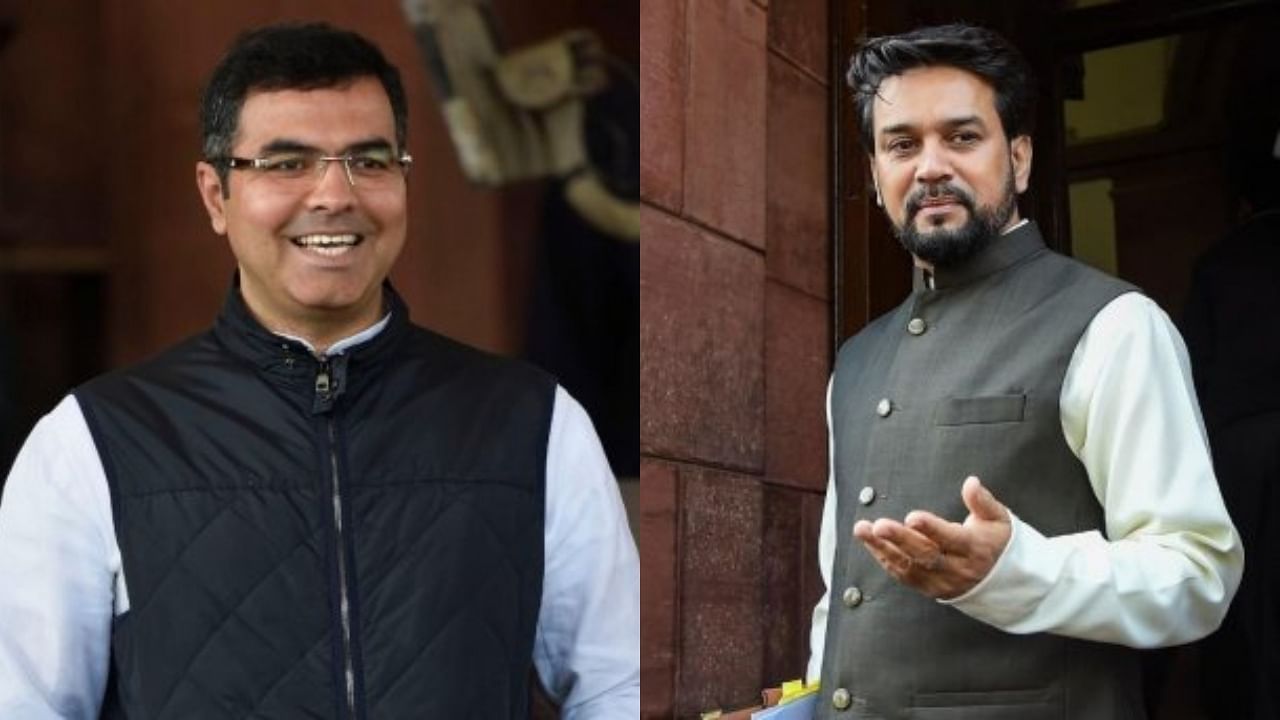

Any chance that Union minister Anurag Thakur will feel ashamed of his "goli maaro saalon ko’’ speech after these strong words? Delhi High Court Justice Chandra Dhari Singh wrote them in response to a petition asking for an FIR to be registered against Thakur and BJP MP Parvesh Verma for their speeches during the 2020 Delhi Assembly election campaign.

While Thakur, then minister of state for finance, had asked his Hindu audience to shoot "traitors’’ (referring to Muslim women protesting at Shaheen Bagh against the CAA-NRC), Parvesh Verma had warned Delhi’s Hindus that the Shaheen Bagh protesters, who he alleged were supported by CM Arvind Kejriwal, would one day "rape and kill’’ them.

The petition, filed by the CPI(M)’s Brinda Karat and K M Tiwari, was dismissed by the trial court on procedural grounds. The High Court has upheld the dismissal.

Prosecution of those who make hate speeches needs government sanction. The trial court pointed out that this permission had not been obtained; the High Court agreed with it.

While there’s disagreement regarding the stage at which sanction is needed, the very fact that one needs government permission to prosecute those who provoke enmity between two groups, explains why rabble-rousers have been able to get away with spreading their poison.

After all, which government will want its own ministers to face trial? The Election Commission removed Thakur and Verma from the BJP’s list of star campaigners for the Delhi polls, but they faced no action from their party. Indeed, in last year’s Union Cabinet expansion, Thakur was given two additional portfolios. Last month, he walked the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival as India’s I&B Minister. One wonders if the international media knew that this man representing India had asked Delhi’s Hindus to shoot their fellow citizens.

Thakur is just one in a long line of elected representatives whose speeches have promoted communal enmity, an offence under Section 153 A. He’s in august company, with both his former party presidents facing cases under this section. But that didn’t stop either L K Advani or Amit Shah from becoming Union Home Ministers.

When the person duty-bound to uphold the rule of law is himself accused of hate speech, the question of any government sanctioning his prosecution becomes purely academic.

In fact, the Association for Democratic Reforms’ analysis of the 2019 Union Cabinet revealed that apart from the Home Minister, five others had cases pending against them for promoting communal disharmony.

Fittingly, one of them, Nityanand Rai, is the minister of state for Home Affairs, while another, Prahlad Joshi, is the Union Minister for Parliamentary Affairs.

Yet, there has been at least one instance of an elected representative having been convicted for hate speech. In 2008, Shiv Sena leader Madhukar Sarpotdar, municipal corporator Jaywant Parab and up-vibhagh pramukh Ashok Shinde, were convicted under Sec 153 A IPC, for the contents of speeches, slogans and placards in a procession during the Mumbai riots of 1992-93, led by Sarpotdar, then an MLA.

The conviction came from the trial court itself. Like Justice Chandra Dhari Singh, Magistrate Rajeshwari Bapat Sarkar also used strong words: "The accused were seasoned politicians and elected representatives with some maturity… In spite of this…they blatantly gave…speeches exhorting Hindus…instead of discharging their responsibility…of trying to alleviate tension and restore normalcy. Such acts deserve punitive measures to send the signal…that wrongdoing would be punished.” The Sessions Court upheld the conviction, asserting that India was a secular country. The appeal is pending in the High Court.

Spreading hate toward others characterised the Shiv Sena as long as it was headed by its founder Bal Thackeray. His very first public rally in Mumbai in October 1966 resulted in attacks on South Indian establishments. Yet, it took 42 years for a Sena leader to be convicted under Sec 153 A. This could only happen because of public anger at one-sided justice: harsh punishments had been handed down to those who’d carried out the March 12, 1993 bomb blasts, but those who’d laid the ground for the blasts by targeting Muslims in the post-Babri Masjid demolition riots, roamed free. This anger forced the Maharashtra government to set up two special courts exclusively for riot cases. The magistrates gave these cases the attention they deserved and handed down seven convictions in five months – a record.

One-sided justice has helped Anurag Thakur and his ilk flourish. Where’s the public pressure enough to reverse this?

(Jyoti Punwani is a journalist)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.