As the Black Lives Matter protests have spread, statues of prominent figures have been defaced or brought down for their racist pasts. It is unfortunate that amidst this, some have also pointed fingers at M K Gandhi.

Here, lawyer-historian Anil Nauriya charts the evolution of Gandhi’s attitude on the race question as well as his views on the African struggle for rights during the latter's stay in South Africa that spanned 21 years.

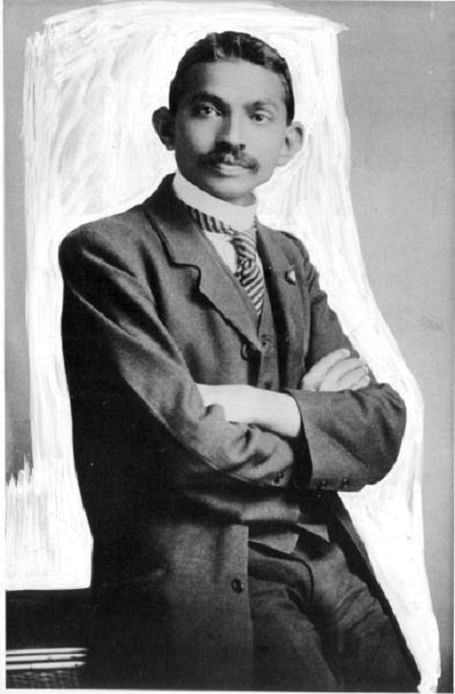

It was in 1893 that M K Gandhi (1869-1948) went from India to Natal in South Africa as a young lawyer, not even 24 years of age. He was not yet 45 when he left in July 1914. Except for a few interludes, mainly in India and England, Gandhi's stay in South Africa spanned 21 years. The widening of Gandhi’s outlook on racial matters goes back to his South Africa years and was not merely a later occurrence as is sometimes erroneously assumed.

The purpose of the struggle against racism is to get people to shed any ethnic or related prejudices they might have. Gandhi is an example of a person who not only shed his earlier ethnocentric ideas but went on to become an inspiration for African struggles and, as stated by the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons on his assassination in 1948, became during his lifetime "the bearer of the torch of liberty of oppressed peoples."

As a subject of the British Empire, as the young Gandhi then saw himself, he sought non-discrimination by the European but resented the reduction in Indian rights whereby educated sections of Indians were clubbed with the ‘raw native’.

But with increased interaction with Africans, Gandhi's concern for African causes became increasingly visible. Though Gandhi’s struggles in South Africa were organised around the Asian causes that more immediately affected Indians, his long-term vision for a non-racial South Africa was by now clear enough, as evidenced by his speech in May 1908, referred to below.

By 1910, Gandhi took voluntarily to third class travel. One of the reasons for this, according to him was that he “shuddered to read the account of the hardships” faced by Africans in the third-class carriages in the Cape. “I wanted to experience the same hardships myself,” he wrote in a letter to M P Fancy, an associate in South Africa, on March 16, 1910. The practice of third-class travel that he would continue in India evidently had this African origin. For such Europeans, as were able to rise above colour prejudice, he usually had a word of praise.

A remarkable change in Gandhi had thus come in South Africa itself. By May 1908, moving beyond expressing his concern merely over Indian issues, Gandhi rejected the policy of segregation and envisioned a South Africa in which the various races “commingle”.

It is in this 1908 speech, made at the YMCA in Johannesburg on May 18, that Gandhi puts forth his vision for future South Africa: “If we look into the future, is it not a heritage we have to leave to posterity, that all the different races commingle and produce a civilisation that perhaps the world has not yet seen?”

The second image depicts a new building that has come up at the same spot.

Source: Johannesburg Heritage Foundation

A citizen of the British Empire

Even as a young Indian Gandhi had a nationalist pride. Queen Victoria's proclamation of 1858 (made a year after the Great Indian Rising of 1857) had committed the British Crown:

"We hold ourselves bound to the natives of our Indian territories by the same obligations of duty which bind us to all our other subjects... It is our further will that, so far as may be, our subjects, of whatever race or creed, be freely and impartially admitted to offices in our service, the duties of which they may be qualified by their education, ability, and integrity, duly to discharge."

To appreciate Gandhi's evolution in South Africa it is necessary to understand that he treated this Proclamation as a Magna Carta for India and Indians and for many years this Proclamation and the British Constitution were his points of reference. He expected to be treated in South Africa the same way as he was when he lived in England while studying law. When confronted with the harsh realities of racial discrimination in South Africa, he insisted on legal equality for Indians with Europeans. Laws in South Africa, however, tended repeatedly to deny the equality that Gandhi believed Indians were entitled to under the Proclamation and the British Constitution.

Asserting citizenship of the Empire, he understood this also to carry obligations. This is what led him on two occasions to volunteer nursing and paramedical service to the British side in the South African War of 1900 and the Bambatha Rebellion of 1906. Although Gandhi participated in the latter, he ended up nursing the Zulu victims and also came to see the justice of the African cause.

Positive attitude on expansion of African rights

Racists seek to restrict the rights of other communities or peoples. Gandhi even in his South African years had a positive attitude on the expansion of African rights. As I have shown in my work, The African Element in Gandhi (2006), Gandhi welcomed African franchise rights as early as in 1894. Gandhi and his paper, the Indian Opinion, extolled outstanding African achievements.

Gandhi supported and welcomed industrial training and general educational efforts among the Africans. While in South Africa, Gandhi reached out to African leaders like John Langalibalele Dube (1871-1946) who was later to be the first president-general of the African National Congress. Dube who, like Gandhi, admired the African American educationist, Booker T Washington, ran an industrial school, the Ohlange Institute, in Inanda near Phoenix. Gandhi set up his Phoenix Settlement close to the Ohlange Institute. "There was frequent social contact between the inmates of the Phoenix settlement and the Ohlange Institute," writes E S Reddy in Gandhiji's Vision of a Free South Africa (1995). Reddy writes that John Dube's paper, Ilange lase Natal, an African weekly in English and Zulu, used to be printed in the Indian Opinion press until the Ohlange Institute acquired a press of its own. Gandhi commended Dube's work as he did that of the leading African editor John Tengo Jabavu to set up a college for Africans.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

As early as in 1905, Gandhi had supported Africans’ rights in land. He and his journal welcomed the Transvaal Supreme Court judgement in the case of Edward Tsewu (b. 1866), another future founder of the African National Congress, upholding the Africans’ right to hold land. Gandhi’s paper severely condemned the Natives Land Act, 1913, as an “Act of confiscation” and supported John Dube’s criticism of the Act.

Gandhi’s notions on race benefited from his intellectual exposure to influences such as those of Olive Schreiner and Jean Finot. Soon after Gandhi's release from prison in 1908, an article by the writer Olive Schreiner in 1908 in The Transvaal Leader arguing against racial prejudice and envisaging a non-racist South Africa, was reprinted with some editorial appreciation in Gandhi’s journal. Gandhi would repeatedly refer to her lack of racial prejudice and made a specific reference to it at the session of the Indian National Congress in Kanpur in 1925. She was clearly one of the vital influences that entered into the transformation and broadening of outlook that Gandhi experienced in South Africa on the question of race, particularly from mid-1908.

Similarly, Jean Finot’s work, Race Prejudice, is another formative but unjustly neglected influence on Gandhi from this period. Gandhi referred to Finot’s work a few months before the Universal Races Congress was held in 1911. The Polish-born Finot had become a French citizen in 1897. In France, he founded and edited La Revue des Revues which brought him into contact with writers like Tolstoy. Finot’s work against race prejudice, Les Prejuge des Races, was published in Paris in 1905. The English language translation appeared the following year. It is this work which was noticed and commended in Indian Opinion in September 1907.

Gandhi’s criticism of the South African Constitution of 1909-1910 was also based on his vision of non-racial nationhood. Gandhi had vital insights into the emerging South African nation and stressed the need for a non-racial conception of it. Gandhi criticises the 1909-10 Constitution for its racist content.

In 1910, Gandhi criticised the racially-based constitutional set-up in South Africa under which an African leader like Walter Rubusana, a future founder of the ANC, was not considered entitled to contest for Parliament although he could be a member of the Provincial Legislature in the Cape. Earlier, in 1904, Gandhi had endorsed Rubusana’s interrogation of Sir Gordon Sprigg in East London and Rubusana’s criticism of discriminatory pavement regulations in that Eastern Cape city.

Supporting political organisations among Africans

Gandhi supported the growth of political organisations among Africans. Gandhi’s paper, Indian Opinion, welcomed the establishment in January 1912 of the African National Congress (then named the South African Native National Congress) as an “awakening”. Six months before the ANC was formed, Gandhi’s paper carried a report about the likely formation of such an organisation. The report cited Pixley Seme (1881-1951), who would reputedly be the main driving force behind the establishment of the organisation, and would later become its fifth President-General.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

John Dube, the African leader from Natal and Gandhi’s neighbour in Inanda, near Durban, was chosen to be the first President-General of the African National Congress; Walter Rubusana became Vice-President. Gandhi’s paper welcomed the choice of John Dube, “our friend and neighbour” and published in detail the ‘manifesto’ issued by Dube.

At least seven years earlier, in 1905, Gandhi had met John Dube and heard him speak. He had then praised John Dube and wrote in favour of African land rights. In the following year in 1906, Gandhi’s paper praised a ‘manifesto’ issued by John Dube against colonial policies that displayed unfairness towards Africans.

When Gopal Krishna Gokhale visited South Africa at Gandhi's invitation, Gandhi took him to meet John Dube on November 11, 1912, at the Ohlange Institute near Phoenix and discuss “matters of politics”. The historic significance of the meeting is immense. John Dube had been chosen as the first President of the African National Congress at the beginning of the year. Gokhale had been President of the Indian National Congress in 1905. After his return to India, Gandhi too would be President of the Indian National Congress – in 1924.

Dube’s paper, Ilanga lase Natal, reported that Gokhale, accompanied by Gandhi and others “was received by our boys and girls who greeted him with cheers and gave him an exhibition of band and vocal music.” The same issue, dated November 15, 1912, carried an editorial on Gokhale’s visit to South Africa. It observed:

“The reception and attention that are being given by the Government and people of South Africa to the Hon. G. K. Gokhale, and the hearing he has received on all sides when he has touched upon the unsatisfactory relations existing between the European and Indian population of the Union, convey a lesson of importance to the Native population. We have seen and heard a great man whose knowledge and experience is equal to that of the foremost statesmen of our day, and he is a black man….We Natives of South Africa have not been given the opportunity of taking part in the affairs of our fatherland, and consequently cannot boast of such leaders as are Messrs Gokhale and Gandhi…. The Natives have taken the most important step in establishing a representative Congress of their own. They should perfect that organisation and support their Congress and men they have chosen to office by every means in their power. Let them speak as those having authority, and the claims of the Natives to attention will at least always have a hearing.”

Gandhi enjoyed the trust of leading figures in the African National Congress. Selby Msimang consulted Gandhi on legal matters in the absence of Pixley Seme with whom Msimang was associated. Pixley Seme himself had called on Gandhi at Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg in 1911. An account of this has become available from the memoirs of Pauline Podlashuk, a future medical doctor who was active in the suffragette movement in South Africa as secretary of the Women’s Enfranchisement League.

Gandhi’s paper welcomed the African women’s anti-pass struggle in the Orange Free State, South Africa in 1913 with a full front-page article on August 2 emblazoned with the banner heading, “Native Women's Brave Stand" in capital letters. In the 1906 Rising, Gandhi had wanted to do what he saw as his duty by the settlers. By 1913 his sympathies had moved to the Africans so long as the struggle was non-violent. One reason for some misunderstanding of Gandhi's position has been his anxiety that struggles ought to be nonviolent and his reluctance to endorse an amalgamated struggle involving all communities until he had satisfied himself that this condition would be met.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Seeing the justice of the African cause

Racial prejudice would be seen in the fact that Gandhi and other Indians who were imprisoned in the passive resistance campaign resented being classed with Africans, especially those convicted for criminal offences. Various reasons contributed to this and while some of these were of a racial nature, Gandhi was particularly irked by the fact that "...this thoughtless classification has resulted in the Indians being partly starved...." (Indian Opinion, March 7, 1908, in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol 8, p.120)

Yet even this resentment was mixed with some introspection by Gandhi: "It was however as well that we were classed with the Natives. It was a welcome opportunity to study the treatment meted out to Natives, their conditions [of life in gaol] and their habits. Looked at from another point of view, it did not seem right to feel bad about being bracketed with them." (Indian Opinion, March 7, 1908, in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol 8, p.135)

In an interview given to D A Rees after his release from prison, Gandhi remarked: "Asiatic prisoners are classed with Natives. I do not object to this, but I claim that they should be supplied with food according to their customs."

Gandhi also spoke out on public health issues in favour of the African people. He criticised racist policies on public health which had “meant death and destruction to the Native people of this country.” Gandhi spoke out against segregation even in the context of a smallpox outbreak. He supported African civic rights and critiqued the jury system for its bias against Africans.

Although Gandhi offered his nursing and paramedical services to the British in the 1906 Rebellion, he came to see the justice of the African cause. It is on seeing this that Gandhi commended passive resistance as a method to the African people. The methods of struggle envisaged by Gandhi were becoming more intensive and defiant. He had reached the end of the petitioning road. In a note Gandhi sent in Gujarati, for his journal of August 28, 1909, he wrote:

“I see the time drawing nearer everyday when no one, whether black or white, will succeed in obtaining a hearing by merely making petitions. If I am right, then no force in the world can compare with soul force, that is to say, satyagraha. I, therefore, wish that Indians should fill the gaols if, by the time this letter is published, there has been no decision or solution.”

He recommends passive resistance to Africans in June 1909 and to the Coloured People. In line with this, he also supported the protest made by the Coloured community at the time of the Prince of Wales visit to Cape Town in 1910.

Arriving at the interconnectedness of struggles

Gandhi had resented the use of the term "coolie" for Indians, particularly the educated sections. He had, however, regrettably himself used the term "kaffir", then current in South Africa, for the Africans. Gandhi’s own vocabulary improved with time in South Africa itself and not merely upon leaving it. Despite kaffir being an expression that had to some extent entered South African usage, Gandhi discarded using it for the Africans before he left South Africa. Gandhi in South Africa gradually grew out of the tendency to use the word kaffir, taking its usage towards the end of his stay there (1913-14) to a vanishing point.

Kaffir was essentially an Arabic term for non-believers. The term, having acquired a special meaning in South Africa as a dismissive synonym for the Africans, had also entered South African laws of the time. Some of the Christian missions of the time also adopted it. The term was also adopted to connote African language(s) and Lovedale Press published a "Kaffir-English Dictionary" at least as late as in 1915. Many Africans used the term themselves. John Knox Bokwe, wrote a "Kaffir Wedding Song" the second edition of which was published in 1894, a year after Gandhi's arrival in South Africa. In the United States, ‘Negro’ has now been discarded as an expression, but so many African American writers in the early years had used it themselves even in titles of books they wrote.

Gandhi understood the interconnectedness of struggles for freedom. In July 1926 Gandhi emphasised a vital axiom about the struggle against racial discrimination which set limits to how far Indian demands could be expected to be met in South Africa without a forward movement in that country as a whole: “I do not conceive the possibility of justice being done to Indians if none is rendered to natives of the soil”. (Young India, July 22, 1926, in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol 31, p. 182)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The same thought recurs here:

“Indians have too much in common with the Africans to think of isolating themselves from them. They cannot exist in South Africa for any length of time without the active sympathy and friendship of the Africans.” (Gandhi in Young India, April 5, 1928, in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol 36, p. 190).

Extending the methods he had adopted in India, in 1926 Gandhi commended worldwide nonviolent non-co-operation against exploitation. Following the economic boycott of foreign cloth that Gandhi had encouraged and sponsored in India, he had been recommending the same course to other Asians and to Africans. He had declared in 1926: “There is however no hope of avoiding the catastrophe” (of increased racial bitterness) “unless the spirit of exploitation that at present dominates the nations of the West is transmuted into that of real helpful service, or unless the Asiatic and African races understand that they cannot be exploited without their co-operation, to a large extent voluntary, and thus understanding, withdraw such co-operation.” (Young India, March 18, 1926, in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol 30, pp. 135-136)

Support to other African leaders

In addition, Gandhi offered his encouragement to African leaders in other parts of Africa, such as Kenya. As early as in 1924 Gandhi had commented on the case of the African leader Harry Thuku, an early organiser of Kenya's African workers. Thuku, who had protested against the flogging to death of some of his countrymen and against forced labour by African unmarried girls on plantations of white settlers, was detained without trial and deported. Gandhi described Thuku as the victim of “lust for power” and wrote that if Thuku “ever saw these lines, he will perhaps find comfort in the thought that even in distant India many will read the story of his deportation and trials with sympathy.”

During his visit to England in 1931, Gandhi had a meeting with Jomo Kenyatta, the future leader of Kenya. Jeremy Murray-Brown, Kenyatta's biographer, writes about the meeting: "Kenyatta met the Indian leader in November 1931, and Gandhi then inscribed Kenyatta’s diary with the words: 'Truth and nonviolence can deliver any nation from bondage'."

As early as in 1931, Gandhi extended support for the independence of the Gold Coast (the later Ghana). With Gandhi already committed to Indian independence, and to full Egyptian independence, his commitment to all of Africa could be no less. While visiting London, Gandhi was asked, on 31 October 1931, a question about the country that the world would later know as Ghana: “For some years Britain would continue certain subject territories like Gold Coast. Would Mr. Gandhi object?” Gandhi replied: “I would certainly object.” When recently the authorities in Ghana decided, under pressure from a university faculty swayed by some recent writings, to remove Gandhi's statue from the campus in Legon, they in fact removed one of the earliest supporters of Ghana's independence.

From Mohandas to Mahatma

In a deeper and more complex way than most, Gandhi understood, as we have seen, the interconnectedness of struggles. Interestingly, so indeed did many of the protagonists who would in the first instance be affected by his struggles, such as the European settlers in Africa. As in Kenya in later years, so in South Africa, there was a general apprehension voiced by the European Press during Gandhi's African years that whatever was conceded to the relatively minuscule community of Indians would sooner or later have to be conceded to the Africans. Hence the stout resistance to conceding Indian civil and political rights.

The Indian struggle was apparently a struggle only on behalf of Indians. Yet it was far wider in its consequences. This was noted for example by the APO, the journal of the Colored people of South Africa, (organised under the banner of the African People’s Organisation) on Gandhi’s departure from South Africa. Much of the evolution in Gandhi's ideas took place while he was yet in South Africa. This is what Nelson Mandela seemed to refer to when he said in effect: “You gave us Mohandas Gandhi, we returned him to you as Mahatma Gandhi"

(Anil Nauriya studied economics and is counsel at the Supreme Court of India. He has been writing since the 1970s and has focused frequently on secularism and the state and on struggles for freedom. His writings in the last two decades include The African Element in Gandhi (2006))