Credit: DH Illustration

Twenty-five-year-old nurse Aruna Shanbaug was sexually assaulted by a male sweeper in Mumbai’s renowned King Edward Memorial Hospital. He choked her with a dog chain and raped her and left her for dead. The assault resulted in brain damage, paralysis, cortical blindness, and cervical cord injury. She was found the next morning, but not dead. This was in 1973.

For the next 41 years she remained in a vegetative state, cared for by the staff of the hospital. They refused to vacate her bed despite pressure from the municipal corporation to move her out of the hospital. She eventually died in the hospital. Many people campaigned for euthanasia for her which was refused by the highest court. Her case led to a landmark legal judgment permitting passive euthanasia in India.

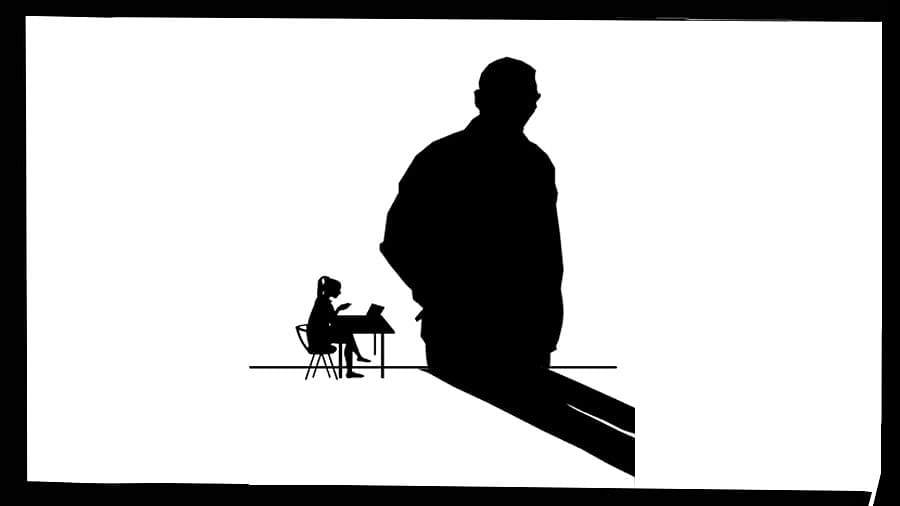

But her ordeal will always remain a blot on society, and a matter of shame. Even after 51 years, as the recent brutal rape and murder of a trainee doctor in a Kolkata hospital tells us, not much has changed. Female doctors and nurses still fear for their safety even inside a hospital. It also strongly highlights the issue of workplace safety for women.

This is one of the contributory factors affecting women’s participation in the workforce. As such, India has had one of the lowest workforce participation rates for females among all G20 countries. It declined from around 30 per cent in 2004 to 20 per cent by 2017. It has improved in the past few years after Covid-19.

The sharp decline is attributed to a variety of supply and demand factors. On the demand side is the reluctance of employers to hire women, either in blue collar manufacturing or in white collar services sector. Work opportunities are not expanding fast enough. Another strange demand side reason is a law which was meant to be women friendly. The national law for compulsory maternity leave, perversely led to less not more recruitment for women.

On the supply side are factors such as social and cultural norms that prevent women from taking up jobs outside home. Or the priority given to household work and caregiving to children and the elderly. Women do nearly 90 per cent of household work, which is unpaid. This ratio is most adverse against women, when seen as male to female sharing of housework across different societies in the world.

In Africa and many Western countries, the share tends to be more equal, but not so in South Asia. Additionally, women workers are much more active in agriculture, where too their work remains hidden and unpaid.

But another important factor is workplace safety. The National Crime Records Bureau reveals that there is a 20 per cent increase in reported gender crimes in the past four years. This is an underestimation because a large number of crimes go unreported — for fear of reprisal, the stigma attached to the victim, and no confidence in police investigation.

The case of the 2001 Kolkata rape from the same hospital proves how investigation was botched, and the perpetrator was not punished. There are the additional factors of the victim blaming syndrome and misogynistic attitudes which deter women from lodging formal complaints.

There was an advisory from Assam’s Silchar Medical College Hospital urging female students and doctors not to venture out at odd hours. This is not an isolated example of societal attitudes whose message is, women be careful, there are rapists out there.

In a 2021 research paper by Tanika Chakraborty and Nafisa Lohawala, the authors estimate the impact of fear of violence on female participation rate in the workforce. They report that ‘For every additional crime per 1,000 women in a district, roughly 32 women are deterred from joining the workforce.’ It is not just the prevalence of crime but the threat of sexual violence that can deter women from taking up formal sector jobs.

This results in a sort of self-censorship, i.e. a supply side factor curtailing participation. The irony is that female enrolment in colleges and higher education is rising, and they often outperform their male colleagues in academics. In most medical schools the incoming female enrolment is more than 50 per cent, but the proportion of practicing female doctors is still less than 15 per cent. This is a national loss, if a woman doctor is lost to society. It is not just for child and family care that she drops out, but it could also be due to workplace safety issue.

After the Nirbhaya case, the laws were tightened against sexual violence. We also have stringent laws against child abuse. Yet the laws have not stopped reported sexual crimes from growing as the NCRB data shows. The issue of rising sexual violence against women is not just a matter of ensuring more safety and getting justice. It also adversely affects India’s economy. India’s low female labour force participation rate is coupled with a gender wage gap. This makes it a double whammy. If both these issues are addressed there will be a big jump in employment, earning and output.

It is as if India is ignoring the immense growth potential of half its human capital. The policy solutions to increasing women in the formal employment are manifold. For instance, in Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe championed ‘womenomics’ of which one major component was starting half a million State funded high quality crèches.

In India too there will be legal, fiscal and social policies to encourage more women to join the workforce. This could also take the form of reservation of certain jobs only for women, or providing them free public transport, or exempting them from income tax. Culturally too the attitudes and language have to reflect granting women more autonomy for their decisions, and acknowledging their identity independent of just being a dear ‘sister’, ‘mother’, ‘wife’ or ‘daughter’, i.e. only defined in relation to males.

Most of all let us not forget that workplace safety will remain a prime concern. If women must constantly worry about the threat of sexual violence at work or in public places, that will always be a negative factor in increasing their participation in the workforce.

(The writer is a Pune-based economist)

(Syndicate: The Billion Press)