On September 6, 2019, a Supreme Court bench comprising of Justice L Nageshwar Rao and Hemant Gupta dismissed a civil appeal filed against forest clearance granted to the Yettinahole water diversion project in Sakaleshpura taluk of Hassan district of Karnataka. The SC stated that in view of the “peculiar facts” of the case, they are not inclined to interfere.

It becomes imperative to understand what is ‘peculiar’ to the case. Do the peculiar facts warrant non-interference by the court?

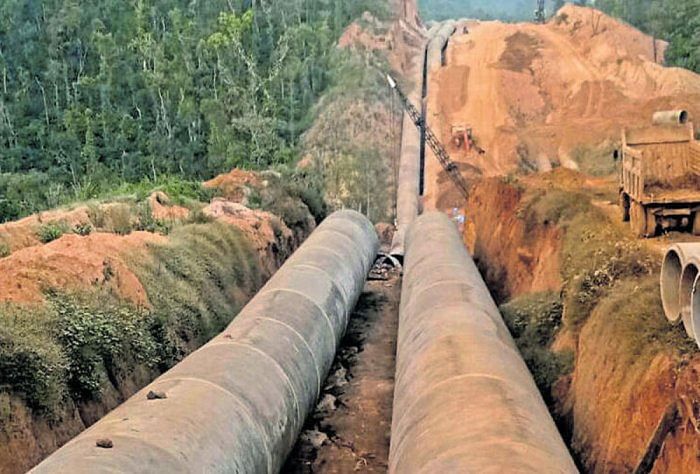

The Yettinahole project involves the transfer of water of the Nethravati river located in Hassan district to the districts of Chikkaballapur, Tumakuru, Ramanagara, Kolar and Bengaluru Rural where water levels are low due to ‘over-exploitation’.

The project required a prior forest clearance from the Centre since it involves diversion of forest land. As per the Karnataka Forest Department (KFD), the area where the project is proposed is “evergreen and semi-evergreen forest of the Western Ghats with unique flora and fauna and rich biological diversity. The area is also an elephant habitat with frequent movement of elephants.”

Despite the KFD admitting that neither did the project undertake an Environmental Impact Assessment and the mandatory cost-benefit analysis (which would show whether the benefits outweigh the environmental costs), nor did it consider alternatives to the project, it was recommended for approval.

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate change (MoEF&CC) also approved the project by stipulating that “a study on the ecological impact of the project on the downstream ecosystem may be initiated through a reputed scientific institution simultaneously so as to make a course correction on the conditions to be imposed in future”.

Absurd as it may sound, the MoEF&CC stipulated that ‘study on ecological impact’ on downstream ‘may’ be initiated. This, in simple terms, would mean that only if the project proponent (Karnataka Neeravari Nigam Ltd) voluntarily wants to do an ecological assessment after the project is completed, it may do so. This is not an ecological assessment but a post-mortem study of ecology.

If the executive, led by KFD and the MoEF&CC had completely disregarded statutory rules and regulations as well as environmental considerations, it is imperative for the judiciary, as an institution to uphold to rule of law, to strike down decisions of the executive which are arbitrary, capricious, whimsical and improper besides being illegal.

The forest clearance granted to Yettinahole satisfied all these grounds, yet the judiciary dealt with all the illegality with only one central idea, that all the wrongs can be overlooked because it is a drinking water project. The manner in which the NGT dealt with this is worth highlighting.

An appeal was filed by Somashekar, a social activist from Uttara Kannada in November 2016. The NGT Act requires that an appeal must be decided within a period of six months of filing. The appeal was heard by a bench headed by Justice Jawad Rahim.

On October 5, 2017, almost a year after the appeal was filed, the NGT, in a short one-line order, stated that there are no merits in the appeal and dismissed it. No reasons were given for the dismissal. The order, however, stated reasons for the same would follow later.

The appellant could not challenge the NGT’s order since detailed judgment with reasons was yet to be delivered. The construction work in the project proceeded in the meantime. After four months, the NGT expressed its inability to give reasons since the expert member who had heard the matter had retired.

The appeal was re-heard by a three-judge bench led by Acting Chairperson Justice Jawad Rahim. The hearing ended in May 2018 and the judgment was reserved. However, the judgment was never pronounced, despite being reserved.

Substantial issues

After a year, the case was again listed for hearing— this time by a bench headed by Justice A K Goel. The entire case was heard and concluded in one day (May 13, 2019) and judgment was pronounced on May 24, 2019. And the NGT failed to consider any of the substantial issues raised and approved the project simply because it is a drinking water project.

The fact that the bulk of the construction work was completed while multiple hearings were going on before different benches, substantially weighed against the petitioners.

The facts of Yettinahole are indeed peculiar. These facts, however, should have been the reason for the judiciary to set aside the legally and ecologically wrong decision of the executive. It failed to do so.

While overemphasising the ‘drinking water’ benefit of the Yettinahole project, the judiciary overlooked the fact that the Western Ghat itself is nature’s own and irreplaceable drinking water project, created over millions of years, supplying water to millions of people and sustaining life.

It amounts to a blatant breach of public trust when both the executive and judiciary fail to protect this unique biodiversity hotspot and attempt to replace nature’s creation with a series of dams and pipelines for short-term human benefit.

(The writer is an environmental lawyer and practises before the NGT)