Without being rhetorical and plagiaristic we can say that three score and fifteen years ago our fathers brought forth in this country a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Just as President Lincoln wondered in his speech at Gettysburg, made many years after the founding of the American nation, we also need to ponder whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. At the stroke of midnight, when India awoke to freedom, there were ringing words about its tryst with destiny and how the time had come to redeem that pledge by being free and ensuring that, whatever religion we may belong to, we are equally the children of India, with equal rights, privileges and obligations. After 75 years, we need to see if the covenant that was made at the time of freedom has endured, with the ideas which were part of that covenant.

August 15, 1947, was about freedom, the freedom of the nation and, as importantly, the freedom of the individuals who make up the nation. These freedoms were defined, codified, and declared as the right of all citizens of the republic that was founded over two years later on January 26, 1950. Those freedoms have diminished over the years. Every citizen surrenders a part of their freedom to the State in exchange for the protection of all citizens’ rights. But the State has grown more powerful than it should be, eating into the rights of citizens and slashing the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. The right to speak, the right to eat what we want, the right to dress the way one wants, and other rights, are under stress. The threats come not just from the State but also from others in society. This is not what August 15 promised to the people.

The idea of equality of all citizens has been undermined by the rise of majoritarianism and the adoption and implementation of unequal policies by governments. While Pakistan came into being as the homeland of Muslims, India promised equal treatment for all citizens, irrespective of religion, race, language, and other divisions. That promise has frayed now. From laws like those that criminalised triple talaq and gave a religious dimension to citizenship to restrictive policies that affect the lives of minorities to lawless actions like the bulldozing of homes, the campaign against the minorities has grown over the years. The minorities are being othered and marginalised. This is not what August 15 promised them.

When the country gained independence, it was a collection of princely states and former British presidencies. They merged into a Union of states that developed their own identities and were given substantial powers in their own territories by the Constitution. What was envisaged was a well-balanced federal system where the Union and the states complemented each other and had enough room to absorb and solve the conflicts that might arise. This was the best political arrangement for a country of such wide diversities as ours. This arrangement is being disrupted now with the Union gaining ascendency and dominating the states. There is a push for homogenisation in most areas of life and even in how the past should be viewed and the future should be envisaged. We have too many “one nation, one this” and “one nation, one that” mandates. That is not what was promised on August 15, 1947.

The biggest promise of 1947 was the practice of democracy as the idiom of governance. It was an audacious experiment, inspired by liberal and egalitarian values, to work the world’s largest democracy, with most people poor and illiterate. That experiment worked, and democracy broadened and deepened. Though it was faulty at times and suffered setbacks at other times, the country remained essentially democratic. But that is under threat now. Democratic institutions are under stress, electoral verdicts are upturned, Opposition leaders are arrested and jailed, and their parties broken up and cannibalised. The legislature, which should be paramount in a parliamentary democracy, has been weakened, and the executive dominates it. Doubts have been raised about the judiciary’s independence and ability to protect fundamental rights, especially in the light of some judgements that have caused disquiet and the many issues of constitutional import pending before it for long. Tolerance is the ruling creed of a democracy, but intolerance rules in politics and society now. Majoritarianism rules.

The State is by nature repressive. It is to ensure that the State does not trample upon the citizen’s rights that the Constitution placed fundamental rights at its core and sought to protect the citizen’s civil and human rights with a democratic system of governance. In that system, rule of law prevails over arbitrariness, separation of powers balances the organs of the State, and institutional safeguards check excesses of power. This system is unravelling now: the State can ride roughshod over the individual citizen, duties can get the better of rights, and an extreme nationalism is fizzed up and legitimised. That is not the idea of nation that was born in 1947. It was a humane, accommodative and inclusive vision of India that inspired the freedom struggle and took shape when the country came into its own.

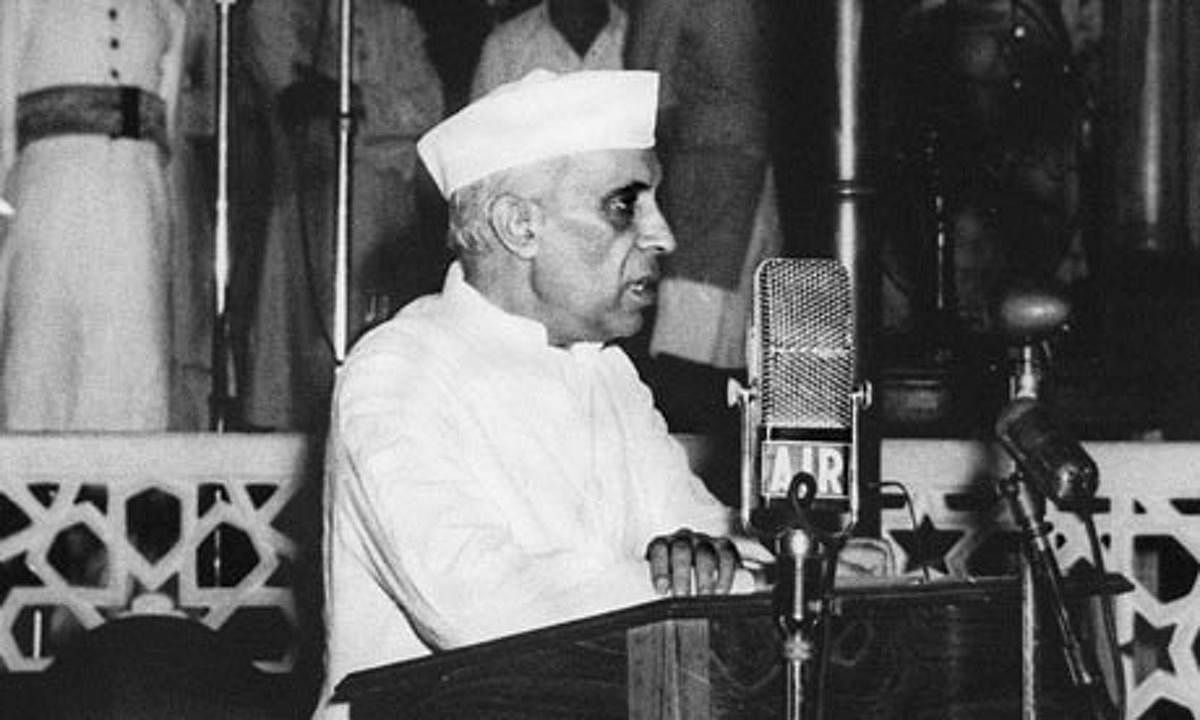

That idea started shifting soon after 1947. Jawaharlal Nehru, who had evocatively put forth the idea at the dawn of the nation, moved the First Amendment to the Constitution in 1951 which restricted fundamental rights, including the freedom of expression, and used Article 356 to dismiss an elected state government (in Kerala) in 1959. Indira Gandhi declared Emergency and suspended the Constitution some years later. Rajiv Gandhi appeased both majority and minority sentiments. The despoiling of the 1947 vision has continued through parties and Prime Ministers, and the decline has become quicker and more decisive in recent years. We are being turned into a confrontationist, exclusivist, majoritarian India.

The country has made many great achievements in its 75-year journey from 1947. Its arrival on the world stage was itself a great event. It has withstood many challenges, lifted millions of people out of poverty and illiteracy, and made strides in all fields of life. It has aspirations to be a superpower. British Prime Minister and colonialist Winston Churchill had said, “India is merely a geographical expression. It is no more a country than the Equator”. But India has proved itself to be a country and a nation and has survived. It still has got more to prove. The jubilee is the time to reignite the hope that was born in the midnight moment of the birth of the nation and to dedicate ourselves to the values that underlay the idea. Let that hope, diamond-bright, sustain and endure.

To return to Gettysburg: In his seminal address, Lincoln described democracy as government of the people, by the people, for the people and hoped that the nation’s life in freedom would ensure that it would not perish. What Lincoln meant was government of all people, by all people, for all people. It was the same sentiment that Jawaharlal Nehru expressed when he asked “Who lives if India dies and who dies if India lives?” If that sentiment should come true, the idea of nation should have freedom at its heart, and the Idea of India as it was conceived in 1947 should be retrieved, restated, and fleshed out again.

(The writer is a former Associate Editor and Editorial Adviser of Deccan Herald)