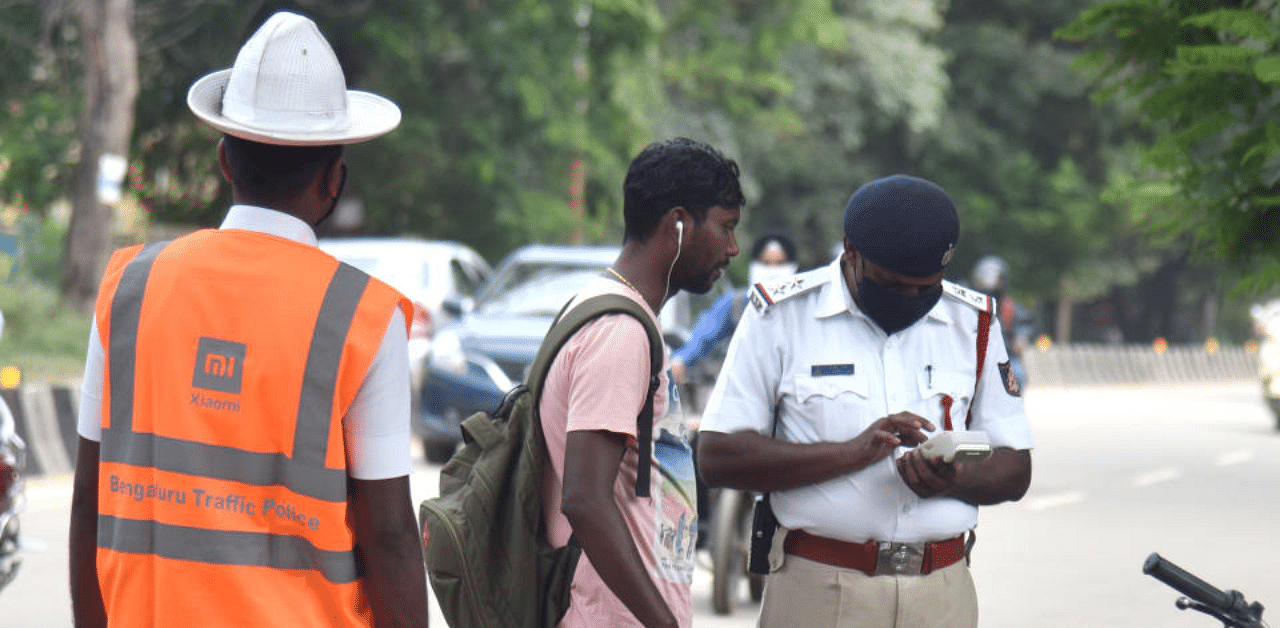

A move by the High Court of Karnataka to set up virtual courts for traffic challans might not just reduce the burden on courts but also lessen Bengaluru’s traffic woes.

Under a new system, inaugurated on August 6, 2020, fines can now be paid online for uncontested minor traffic offences, without having to physically appear before the courts. These offences are drunken driving; alteration of motor vehicles; driving without registering the motor vehicle with the RTO; driving without a permit or violating permit conditions and not exhibiting display cards for motor vehicles with permits.

The move to virtual courts for payment of these fines has been lauded for leading to speedy disposal of such cases and for not clogging the judiciary, which can better spend its time in the adjudication of more serious offences. It can also have a spinoff benefit for the management of vehicular traffic in Bengaluru, a point to which we will come to later.

But first, in order to understand the likely impact of these virtual courts, it is important to analyse how these cases were progressing in regular physical courts before the virtual courts were introduced. An analysis of cases before the six Metropolitan Magistrate Traffic Courts in Bengaluru can help shed light on the likely impact of the virtual court for traffic challans.

An analysis of 33,108 disposed cases, as of November 2019, was taken up from the DAKSH database. Relevant cases were identified based on the Acts and sections to which the cases were tagged. The analysis showed that a large majority (83 per cent) of the cases were regarding drunken driving. While cases pertaining to the relevant section (Sec 185), took an average of 15 days to be disposed, it was found that cases regarding Section 192 (using vehicle without registration) took the most time to be disposed (34 days), and cases regarding Section 192A (using vehicle without permit) took an average of 1 day to be disposed.

Since a large volume of the cases relate to drunken driving, it is interesting to further look at these cases. Contested drunken driving cases took an average of nine days to be disposed, while uncontested drunken driving cases took 50 days to be disposed. A closer look at the uncontested drunken driving cases showed that while 84 per cent of these cases were disposed on the date they were filed, the remaining cases took longer – five per cent of the cases even took over 500 days to be disposed.

A possible reason for uncontested cases taking this long could be due to the non-appearance of the accused. For example, one case which took 614 days to be disposed went through 21 hearings, but was eventually disposed for the continued non-appearance of the accused. It is hoped that the new system will reduce delays of this kind.

Benefits for Bengaluru’s traffic police

Allowing for access to pay fines and clear cases in the virtual court 24/7 will go a long way in making the system easily accessible, reducing the time taken to dispose cases, as well as reducing the workload of courts. Further, if tracking and monitoring of cases before the virtual courts is carried out in a systematic and effective manner, it can also help the Bengaluru’s traffic police understand where most traffic offences seem to be registered.

While one third of these traffic cases have not been tagged to any police station in the court data, the remaining two thirds of cases were tagged to 72 police stations. It was also seen that the top police stations which had the highest number of cases tagged to them were Kumaraswamy Layout Police Station (PS), followed by Yeshwanthpur PS, Basavanagudi PS, and Malleshwaram PS.

Analysis of data and e-filed documents from the virtual court for traffic challans can help the traffic police in identifying patterns in the offences committed in different jurisdictions, adjusting traffic police deployment, easily identifying vehicles with repeated violations and offenders who frequently violate the law. They can also study the reasons for which alleged traffic offences are contested by violators, and refine policing measures to improve adherence to traffic laws.

While the virtual courts for traffic challans have thus far been hailed as a measure to unclog courts and reduce judicial delays, there exists an untapped opportunity for Bengaluru’s traffic police and it is hoped that this will also result in improved policing and reduction in city massive traffic problems.

(Shruthi Naik is a lawyer working at DAKSH Society in Bengaluru, a non-profit organisation working on judicial reforms)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.