In post-independence India, Panchayati Raj came to be regarded as the solution to local-level issues faced by villagers. And West Bengal is usually considered one of the states where the system has been better implemented. But what is the truth?

By now, widespread corruption in the allocation of Awas Yojana housing for poor villagers in Bengal, the prevalence of ‘cut money’ in the allocation of construction contracts and monetary benefits under various government schemes, and the payment of hefty bribes in exchange for government jobs are all well documented. All these are on top of scams involving crores of rupees of bribes passing hands at different levels in appointing teachers, paramedical staff, and municipal workers by falsifying records, jumping queues, and violating due processes. It is quite possible that these cases are being probed and unearthed by central agencies in Bengal because Bengal has been a non-BJP-ruled state for several terms. If so, it is highly likely that similar instances of scams and corrupt practices are prevalent, though not yet widely publicised, in many other parts of India as well.

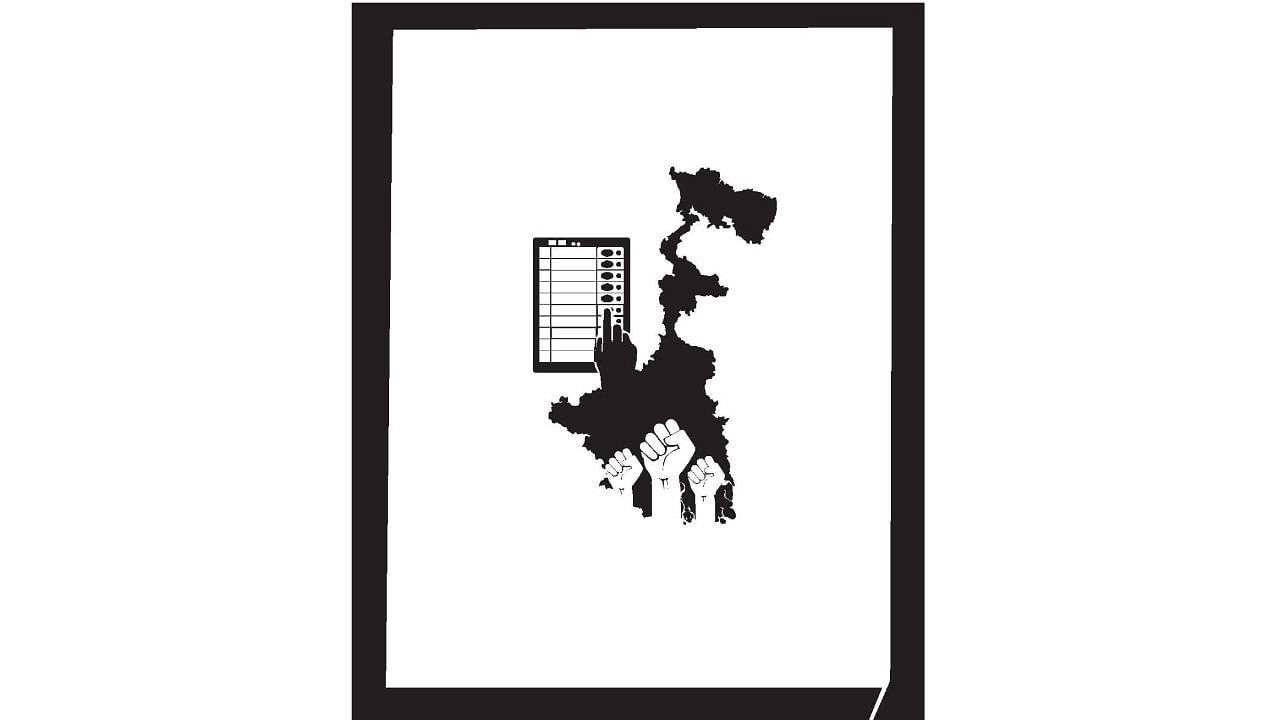

Given the well-publicised probes and instances of corruption unearthed by court-monitored investigations, the ruling party TMC in Bengal is currently in a tight spot in the forthcoming panchayat elections to be held on July 8. In earlier elections, a large number (in some districts, even 100 per cent) of panchayat seats were won by TMC candidates unopposed, as no opposition party even dared field candidates under threat of violence by the ruling party. This time, the situation has somewhat improved for the opposition parties, as their support base has increased because of discontent with the sitting TMC candidates. This is primarily due to the corruption and scams mentioned above and because many people who got jobs by paying lakhs of rupees in bribes (sometimes by taking loans or selling their land and jewellery) to TMC politicians have now lost their jobs because of court orders.

The emboldened opposition politicians and dissident local leaders of TMC (who have not been able to get a share of the spoils of power) who are either switching sides or filing nominations as independent candidates are making the task tougher for TMC. Left parties that lost power to TMC under Mamata Banerjee’s leadership more than two decades ago have been able to consolidate their support base due to the anti-incumbency factor, and, given the short public memory, many people seem to have forgotten or forgiven the misdeeds of the Left during their four decades of rule in Bengal.

In several places, the Left, Congress, and BJP have forged informal alliances and have fielded a single consensus candidate to fight TMC. Resistance by anti-TMC forces, if necessary, by violent means—especially helped by the alienation of a section of the traditional minority votes from TMC in several places—against the advances of TMC goons has noticeably gone up in many parts of Bengal, resulting in violent clashes, loss of lives, and open use of guns and bombs from all sides. The courts, along with the Governor of the state, have also intervened to allow opposition parties to file nominations where otherwise they were not able to do so.

The corruption of TMC has become the main election issue. TMC, on the other hand, is banking on the personal clean image of the CM (though that has been dented to some extent by corruption charges being probed against people close to her) along with the benefits from the numerous welfare schemes rolled out for the poor in Bengal by the TMC government like Lakshmir Bhandar (monthly monetary dole for all women), Kanyashree (annual scholarship for girl students), Sabujsathi (free bicycles for girl students), Swasthathi (Rs 5 lakh hospitalisation cover), student credit card (Rs 10 lakh bank loans for college and professional education), and ration at the doorstep. TMC is also assuring that this time no corrupt politician will be given tickets and candidates will be selected based on secret polls conducted at the village level, even if he or she may have belonged to another political party. This plan has run into trouble as ballot boxes have been broken by disgruntled local leaders of TMC.

To win elections, TMC is apparently using several models. Where candidates from opposition parties have filed nominations or disgruntled TMC leaders have joined the fray as independent candidates, all kinds of threats against them and their families are being used to force them to withdraw their nominations. Where everything else is failing, the TMC leadership is planning to induce the winning candidates of other political parties to join TMC after the polls.

Lastly, the role of the State Election Commission (SEC) and central paramilitary forces has attracted attention. A retired IAS officer, who has been chosen as the State Election Commissioner, has been trying his best to prevent central paramilitary forces from coming to Bengal to ensure free and fair elections without fear or violence. When the SEC lost the case in the High Court, it moved to the Supreme Court and again lost there. In the process, valuable time was wasted. Only then did the SEC reluctantly agree, but it is still using various dilatory techniques so that the Central government does not get time to send enough forces. The SEC has also rejected the suggestion of conducting polls in several phases (as was the case last time) so that the limited paramilitary forces can be used most effectively without spreading them thin.

The opposition and the people at large have little faith in the local police being unbiased or effective in stopping violence during polls and afterwards. The TMC leadership is boasting that they will win elections hands down, irrespective of the presence or absence of central paramilitary forces.

However, the issue is not who will win elections but whether the polls can be conducted in the prevailing atmosphere in Bengal without fear and violence by relying exclusively on the state police and local administration.

So, altogether, a very unfortunate situation, almost bordering on anarchy, is currently prevailing and is expected to continue in Bengal before, during, and after the panchayat elections. And if this is the reality in Bengal, presumably the situation is no better, if not worse, in some other states.

Surely, the advocates of Panchayati Raj did not foresee this.

(The writer is a former professor of economics at IIM, Calcutta, and Cornell University, USA)