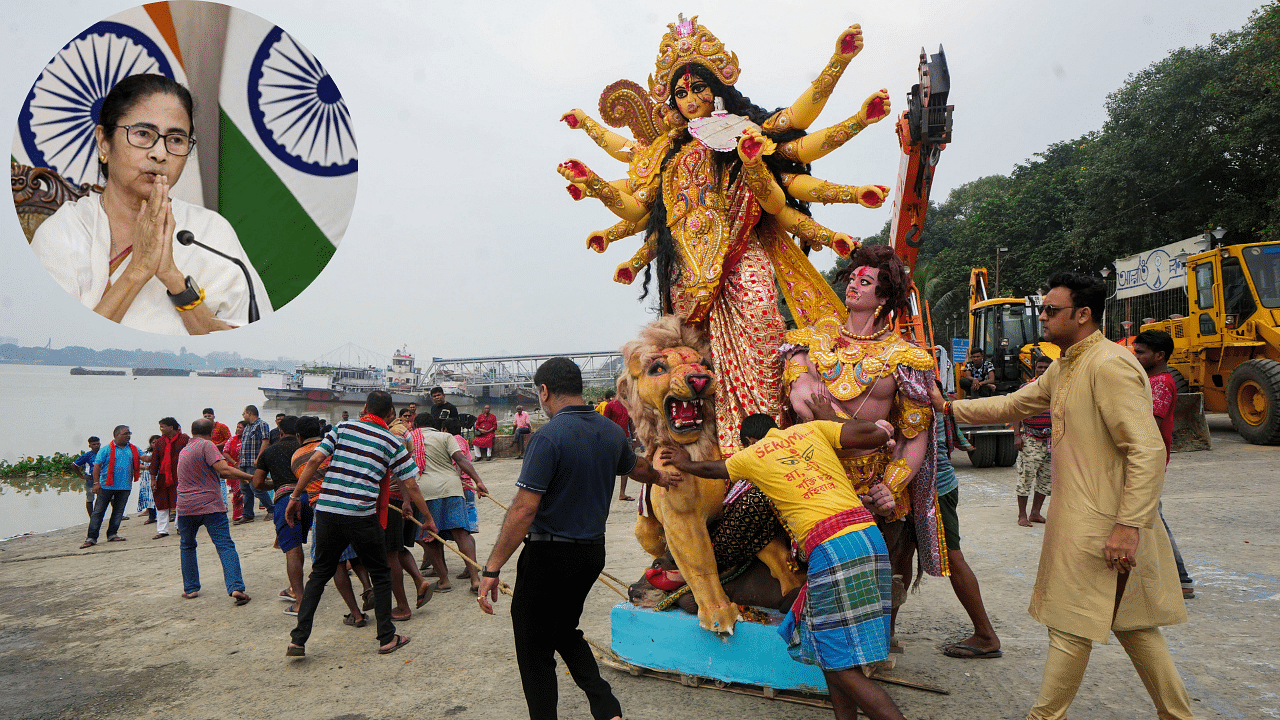

A Durga idol being taken for immersion. (Inset: West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee)

Credit: PTI Photos

Durga puja, a joyous exuberance with immense cultural, socio-political, and economic significance for Bengalis, was not the same this year. The pandals and the processions notwithstanding, a rebellious spirit set the predominant mood for this pujo.

Kolkata witnessed two contrasting ‘carnival’ scenes on October 15, barely three kilometres apart. A human chain of the protesters on one side, barricades erected by the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) government on the other. A display of exasperation versus power-blind arrogance — a figuratively and literally poignant moment as a rebellious carnival of protesters juxtaposed a stark reality against the grand star-studded puja procession by the West Bengal government.

The narrative began with the Nero-esque call to ‘return to festivities’ that followed the initial movement by Kolkata’s junior doctors protesting the rape and murder of the trainee doctor at R G Kar Medical College and Hospital. The festivities did go on. More importantly, so did the ‘fight’ for resurrecting the state’s dwindling healthcare infrastructure and gender justice.

On October 5, the junior doctors began an indefinite hunger strike — those continuing, are battling permanent organ damage.

On the other hand, aggressive reactions from the government, its police, and TMC politicians played out. MP Kalyan Banerjee mocked the doctors, saying it was not a hunger strike ‘unto death’ since the doctors were hospitalised much before they faced ‘death’. This deliberate use of the word ‘death’ could turn ominous and herald the death knell for the TMC government.

After the rape and murder of a 9-year-old from the state’s Jayanagar area, on October 7, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee instructed the police from the festival stages to be strict in handling the protesters. On October 9, a ‘cautious’ police slapped non-bailable sections and arrested nine protestors near a pandal for shouting ‘We want justice’—later, revoked by the Calcutta High Court.

The movement was also replete with symbolism — the junior doctors presented the then Kolkata Commissioner of Police, Vineet Goyal, with a medical replica of the spinal structure, hinting at the lack of it in the ruling administration. On October 15, the police imposed prohibitory orders under Section 163 of the BNS to impede the ‘Carnival of Rebellion’.

The apathy of the government toward this layered movement is glaring. Even its recent damage control attempts fail to invoke trust; forget hope. The TMC has swerved far from its Maa, Maati, Manush (Mother, Soil, and People) rhetoric, forgetting the people’s mandate.

In West Bengal, the height of such power-blind arrogance was last seen between 2006 and 2011, during the Left Front rule. Electoral politics follows a Macbethian narrative: nothing is permanent, and no power is invincible. Banerjee seems to have forgotten this.

Once a much-celebrated fiery daughter of West Bengal, today Banerjee has become the very ‘ruler’ she detested. Once a beacon of ‘change’ in West Bengal, she is now the epitome of autocracy.

Enter anti-incumbency which is possibly at its peak now. Even though the TMC managed to grab 29 Lok Sabha seats in the 2024 general elections, the urban popular opinion swayed significantly.

Welfare policies like Lakshmir Bhandar or Kanyashree, which provide financial assistance to disadvantaged women and girls in West Bengal, could have laid the foundation for solid support for the TMC government. While such policies are welcome, populism will not garner people’s trust.

In fact, these policies magnify the irony — the women population these are meant for are themselves ‘unsafe’. In October, West Bengal witnessed at least seven major reported cases of crimes against women and girls. The state which is fraught with a disparaging threat culture from the party-supported goons, falling employment opportunities, corruption, and political violence, is bound to experience a deteriorating law and order situation, leading to an increase in gender-based violence.

Assembly elections are slated for 2026. It is time to revisit the ‘lesser evil’ argument while voting for the TMC. The relativity of this ‘lesser evil’ paradigm has long muddled the state’s political imagination — an unfortunate trajectory of responding conservatively to anti-incumbency. ‘Evil’, let us not forget, looms on the other side too — the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s communal politics. We are also aware of how the BJP deals with protests.

The TMC’s undemocratic fervour is not new. Prominent past instances include the arrest of Ambikesh Mohapatra for sharing a meme on Banerjee in 2012, and the party chief walking out from a live TV show after being questioned on the party’s hooligan culture. The high defection rate from the TMC to the BJP indicates that the politicians share a comparable ideological grounding, replete with opportunism.

The highhandedness of the TMC government will smoothen the BJP’s path. Parties notwithstanding, the greatest ‘evil’ is the authoritarian State itself, and it is this authoritarianism that must be fought. That’s what Durga puja stands for — destroying ‘evil’.

(Debangana Chatterjee is Assistant Professor, National Law School of India University, Bangalore.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.