“What a dénouement”, exclaimed a professor-friend of mine on coming to know of Modi’s move to enthuse upper castes with a 10% quota. This panic move, a failed idea put in cold storage in the 1990s, is another sign of Modi’s mind on his prospects of coming back to power.

Should the prime minister of the country end up with one more ‘jumla’ in the name of quota for upper castes, that too at the fag-end of his tenure? What has happened to his proclamation, ‘sab ka saath, sab ka vikas’? Any credible report card made available on that?

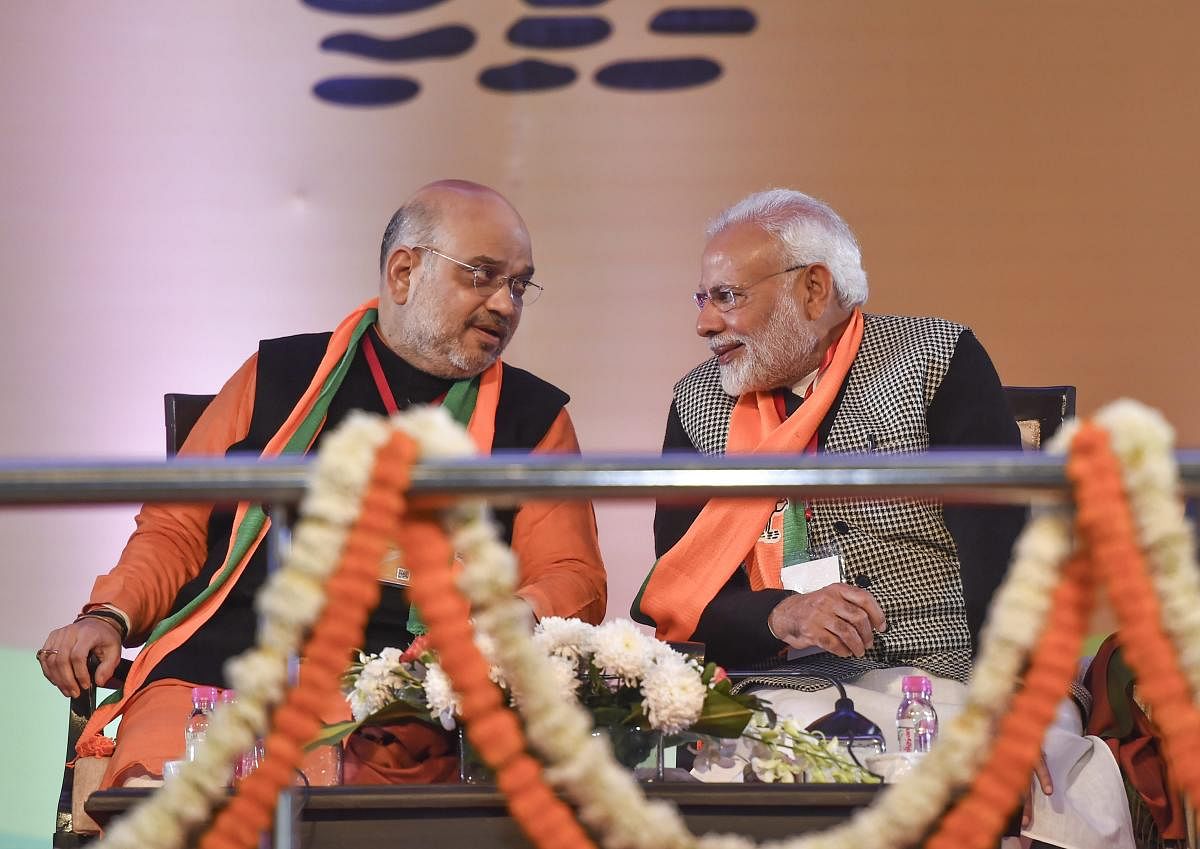

The angst behind these questions are manifold, all pointing to how Modi’s governance has gone astray: the people in general are of the view that but for the media-hyped ‘progress of the country’, manipulated by the Modi-Shah combine, there is no tangible sign anywhere in India that his vision of development has reached the masses on the count of ‘eradicating poverty, Make-in-India, Skill India, job prospects, or Swachh Bharat’. Upward indexing of the country based on sheer material growth, pleasing to the World Bank, or to the Indian diaspora, or to the industrialists, is no guarantee that development benefits trickle down to the masses. The image-building he has personally cultivated, courtesy ‘assenting media’ and its huge costs, cannot be the yardstick to measure the progress of the nation.

Flawed thinking and calculated aberrations to arrogate power, as if governance were a one-man-show, seem to have diseased his vision. Despite the enormous political clout Modi enjoys, despite taxes generated through varied measures during his tenure and despite the huge infrastructure at his command, Modi has failed to deliver in terms of his vision of development.

It is moral outrage to see that during his tenure, the fight against poverty and inequality of income -- tackling the growing rich-poor divide -- has seldom been addressed. As the latest Oxfam report demonstrates, the top 1% of India’s population amassed 51.53% of the total national wealth and the bottom 60% struggled with 4.8%. As it comments, “the inequality between the top 10% and the rest of India has widened, fuelling public anger”.

Modi’s aberrations, moving away from his proclaimed vision, reflect his failure on multiple fronts: farmers’ distress, unemployment crisis, growth benefiting chosen ones among rich industrial giants, under-employment among the youth, both employable and unemployable, and minority-baiting in the name of Hindutva have become aggravated during his tenure.

His moves to subvert the autonomous functioning of institutions like RBI, CBI, and Enforcement Directorate, with the sole intention of safeguarding self-interest and indulging in taming political rivals are disturbing. His vituperative language against opposition leaders and parties, wherever and whenever he wills, does not go well with his self-proclaimed credentials as a visionary leader.

This is how the prime minister has facilitated the withering of his vision into a cluster of ‘jumlas’. When emerging India under his leadership continues to struggle with such aberrations — political, procedural, ethical and moral — marking that he and his party are no different from other political leaders and parties in terms of governance, it is inevitable that his leadership for one more term is viewed as a liability rather than an asset.

‘Modi vs Modi’

The subtlety with which he maintains his affinities with crony capitalists, the giants of a few chosen and preferred corporations, the speed with which he got the 10% quota bill passed, the alacrity with which he moved against former CBI chief Alok Verma, the exit of RBI governor Urjit Patel, the haste with which he came up with the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill with religion as its basis, and the readiness with which he travels across continents all stand in sharp contrast to the deadening silence and stinging indifference he has maintained over the plight of farmers, over the predicament caused by unemployment, over the frauds in the banking system, over his government’s imminent spending of Rs 1 lakh crore on pre-election handouts, over the pathetic mismanagement of higher education in the country, over the atrocious right-wing cow vigilantism and the demeaning harangues against minority communities, over the sickening communal polarisation and over the disdain he has for his opponents.

The calculated political game his government and his party play over the rights of Muslim women, in contrast to the rights of Hindu women of a certain age to enter the Sabarimala temple even after the apex court’s judgement, the flawed thinking in announcing demonetisation without anticipating the painful negative impact it has caused, the undue delay in appointing a Lokpal and empowering him to unearth black money and tackle corruption, and the delay in ushering in comprehensive reforms in higher education may be counted as other areas which make the socially conscious citizenry become sceptical of the prime minister’s intentions and leadership.

If only Modi, as prime minister, had listened to intellectuals who are objective and balanced in their views, if only he had extended statesman-like gestures of political sagacity and dialogue towards his political opponents, if only he had interacted with the media who were discerning and courageous enough to criticise his wrong moves, and if only he had gone beyond his trusted kitchen cabinet and his willing lieutenants at the PMO, Modi’s vision would not have turned out to be an empty gong, full of sound and fury with much ado about nothing vis-à-vis the development of the masses, and the disparate opposition parties, flexing their muscles towards a united front, would not have resorted to an agenda of ‘Modi-mukt Bharat’ with such vehemence.

(The writer is a professor of English, formerly with the University of Mysore)