China is building an ambitious railway line, about 3,500 km in total length, that will connect Chengdu in its east to Hotan in its west, across the Tibetan Plateau. It will run through Aksai Chin, a region we claim is part of India, and close to China's border with India, Bhutan and Nepal.

Two sections of this line have been built and put into operation in the past 10 years. The first section from Lhasa to Shigatse, 253 km, was completed in 2014. The second section to connect Lhasa to Nyingchi, 435 km, was completed in June 2021.

The westward extension from Shigatse to Pakhuktso, to be completed by 2025, should be of great concern to us as that line will pass through Rutog and around Pangong Tso, near where the deadly Galwan Valley clashes took place in June 2020 in which 20 Indian soldiers were killed, on the Chinese side of the LAC.

The eastward extension from Nyingchi to Chengdu in Sichuan province is under construction. The 1629-km eastern part of the line from Chengdu to Lhasa is said to be the most challenging railway project in history.

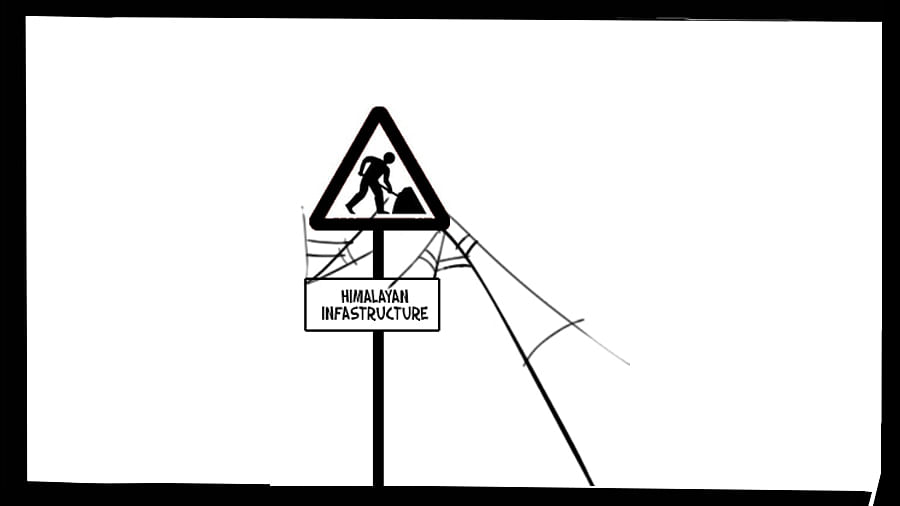

How is India responding to this challenge? The note for the approval of the Kashmir Rail Link was sent to the Cabinet Committee as far back as 2002. Construction began in early 2003 as a project of national importance. Twenty-one years have passed, but the line remains incomplete. In 2008, then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh announced the linking of five north-eastern state capitals by rail by 2015. They are still under construction and unlikely to be completed before 2030.

The main drawback with these projects has been that construction work was kickstarted without proper ground survey and alignment design as the alignments were prepared without factoring in the geological, geotechnical conditions in the extremely challenging terrain through which these lines pass.

The same malaise was recently witnessed in the case of the Silkyara road tunnel, where senior geologists pointed out that something as basic as tectonic fault-lines was not taken into consideration before construction work started on this tunnel.

A retired chief railway engineer, Alok Verma, describes his own experience on the Katra-Banihal rail link and the above mentioned project in the north-east to illustrate where the railways majorly blundered and, when taken to task by the Sreedharan Committee that reviewed their work, refused subsequently to take corrective action.

Verma was brought in to develop a fresh alignment, which he and his team took four years to prepare (2004-8), which was different from the conventional slope-skirting type of alignment that had been prepared earlier.

Work was suspended on the Katra-Banihal line in August 2008, and the Railway Board brought in a committee of external experts to examine Verma’s proposal that construction start afresh as per the new alignment. But as happens in government departments, this plan was scuttled, and Verma was transferred, although 75% of the earlier plan was changed.

A PIL saw the Delhi High Court order the Railway Board to appoint a new expert committee to examine Verma’s proposal. By this time, Rs 5,500 crore had been spent on this construction. Both the CAG and the Public Accounts Committee of Parliament (2012-14) also asked the Railway Board to fix responsibility for the loss incurred by the earlier wrong alignment, but despite this indictment, the Verma proposal was not accepted.

The result of this steam-rolling has been the extremely high cost of construction at Rs 400-700 crore per km of route length, which is about 8-10 times higher than the average cost in other mountainous regions of the country.

Further, the mid-course changes in the alignment in order to deal with geological surprises have resulted in a reduced line capacity, which means just eight to 10 trains per day. This is half the capacity of the existing lines in hilly terrain, such as the Konkan Railways.

The inability to take corrective steps has meant that the railways have had to spend huge sums of money on slope-stabilisation measures of doubtful longevity. This is presently being carried out in a total of around 40 huge bridges and 35 tunnels of 5- to 15-km length in order to glue and stitch together the crushed, fragmented, or rubble-like rock strata. Many 50- to 100-meter-high slope cuttings that are being built will pose a grave risk to the safety, stability, and survivability of each of these lines since major earthquakes and excessive rainfall events are a common feature on the southern face of the Himalayas where these lines are being built.

The other question concerns the stupendously high bridges that are being built close to the international borders. These include the Chenab Bridge, being flaunted as the highest railway bridge in the world, the Anji Bridge on the Kashmir line, and the Noney Bridge on the Manipur line. Security experts warn that these bridges could be easy targets for the enemy in times of war.

Verma says that the new type of alignment that he had suggested for the Kashmir line turns out to be quite similar to the alignments that China has opted for in its challenging mountainous terrain in Tibet, Sichuan, Gansu, and Xinjiang. Relevantly, the Sreedharan committee said in its report that the new type of alignment developed by Verma could serve as a model for other lines in the Himalayas.

In 2017, the Railway Board approved a final location survey for two major projects, namely a 456-km line stretching from Bilaspur in Himachal Pradesh to Leh in Ladakh and the 327-km Char Dham lines linking Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri in Uttarakhand. Both these projects suffered from serious flaws, and many experts have advised the Railway Board to focus on completing their existing Himalayan projects before taking on new ones.

The last three years have, in fact, seen a surge of approvals for the construction of five mega-road tunnels at those very same high altitudes in Ladakh. Nowhere is it clear if the alignment plans for these tunnels have taken into consideration the impact of high altitude.

Our inability to complete infrastructure projects has caused our neighbours to go into China’s arms. These include Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. For Myanmar, China is building a railway line from Muse right up to Kyaukphyu on the Indian Ocean. The Chinese are using infrastructure to extend their influence and mobility, whether it be by constructing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor being built across PoK, or the rail line cutting across Aksai Chin. Where does this leave India and its security concerns? The government needs to answer this question.

(The writer is a Delhi-based senior journalist)