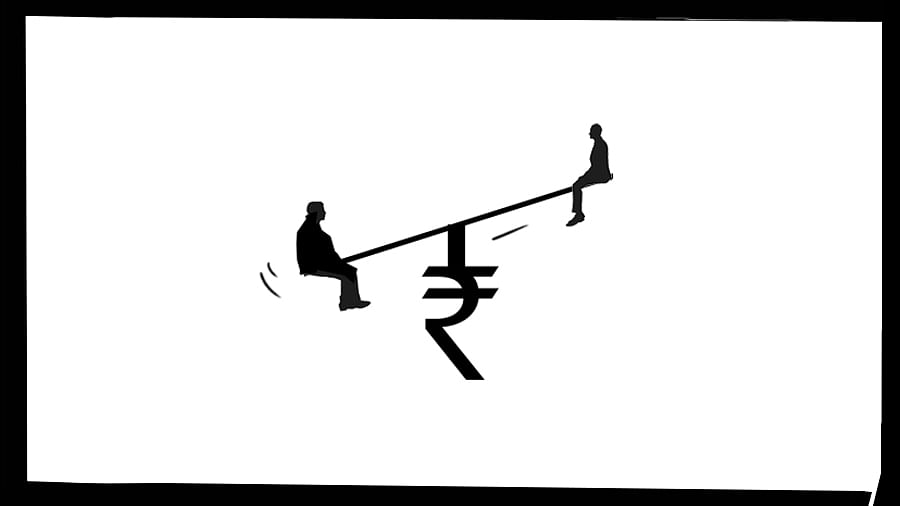

DH Illustration

India has been riddled with inequality for a long time, but it has intensified in recent years, especially during the pandemic. While India ranks fifth in the world based on GDP, and as the fastest growing major economy, this growth has been accompanied by a sharp rise in inequality. According to the recent UNDP report on Asia-Pacific Human Development, in the time that India added nearly 40 billionaires (the count rose from 102 to 143), 46 million other Indians fell below the poverty line.

While India’s per capita income has risen from $442 to $2,389 in the past two decades, that statistic hides the reality that much of the new income and wealth generated has gone to the top 1 per cent and top 10 per cent of the population, while the poor have become poorer. Per capita income growth has also been heavily concentrated in some states – lagging states that accommodate 42 per cent of the total population are home to 62 per cent of those living below the poverty line.

Amidst the GDP growth, therefore, the disparity within the nation has increased both in terms of income and wealth. The highest-earning 10 per cent of the population receive 57 per cent of the country’s total income, with just the top 1 per cent receiving 22 per cent of it, marking one of the most imbalanced income distributions. Likewise, wealth disparities are evident, with the wealthiest 10 per cent of the population possessing over 65 per cent of the nation’s overall wealth. The UNDP report poses an important question: Why has India experienced growing inequality despite notable economic growth in recent decades?

To answer this question, it is important to reflect on India’s planning regime post-Independence, which emphasised on socialism (1950s-1980s), helping to reduce inequality. That approach reduced the concentration of economic power among the rich, and the share of national income that went to the top 1per cent of the population fell from 12 per cent in 1951 to 6 per cent in 1982.

The 1991 reforms brought in liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation of the economy. It led to a series of acts and policies aimed at liberalising the Indian economy to an unprecedented extent. These reforms facilitated an environment for the wealthy to profit from the less-affluent, without repercussions. Data from the World Inequality Database (WID) clearly shows how the share of national income of the top 1 per cent increased steadily, accompanied by a decline in the share of the bottom 50 per cent post-1991.

It has been argued that although the wealthy saw greater financial gains compared to the less-affluent, overall living standards have improved for everyone, suggesting a positive outcome despite unequal wealth accumulation. However, this claim can be disputed using data from the WID on the trend of absolute income of the two income classes. It is seen that post-1991, the absolute income of the top 1 per cent increased drastically, compared to the negligible growth in the absolute income of the bottom 50 per cent.

The assertion that the 1991 reforms were the major drivers of inequality in India gains more support when the Annual Survey of Industries data is examined. In 1981-82, India’s organised sector displayed a net value addition (described as the additional value added in a product during the manufacturing process) of approximately Rs 14,500 crore. Workers received 30.3 per cent of this as wages during this period, while factory owners and shareholders gained 23.4 per cent as profits. The share of wages before liberalisation stayed at or above 30 per cent. However, after liberalisation, there was a noticeable decline in the portion allocated to workers’ wages, even as there was a steady rise in profit shares. By 2019-20, the net value added had risen to Rs 12.1 lakh crore. Remarkably, only 18.9 per cent was directed towards workers’ wages, while profits surged to 38.6 per cent.

A more recent reform that has increased the disparity within India is the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017. Moreover, in the same period, the government reduced the corporate tax rate, ostensibly to encourage businesses within the country to invest. These two factors have contributed to intensifying inequality by increasing the share of indirect taxes and decreasing the share of direct taxes in India’s tax revenue kitty. Indirect tax – tax on goods and services bought/sold -- is paid by every citizen irrespective of their income class. It includes a tax on goods like food and services like accommodation. On the other hand, direct tax is the tax that businesses pay on their profits and citizens pay on their income (above a certain level). Therefore, when the share of indirect taxes in total tax collection is high, it imposes a more equal distribution of the tax burden among unequal citizens. This equal distribution is not equitable since the poor are forced to contribute equally to the tax collected as the wealthy. This drives up inequality, which is just what the introduction of GST has been doing.

The disparity within India has grown to such an extent that minor policies aimed at addressing inequality might prove to be ineffective. Therefore, a more drastic and comprehensive approach must be adopted. Implementing a wealth tax, for instance, could play a significant role in reducing inequality. By taxing the accumulated wealth of the richest individuals, the government could generate additional revenue to invest in social welfare programmes, education, and healthcare, fostering greater economic opportunity for the underprivileged. However, accurately determining the value of assets of the wealthy can be challenging, leading to potential disputes and tax evasion. The wealthy may relocate their assets, or even themselves, to countries with more favourable tax regimes, resulting in capital flight and reduced tax revenue. Therefore, a wealth tax must be carefully crafted to be effective, considering these challenges while striving to strike a balance between reducing inequality and promoting a thriving economy. Further, providing better social security along with aggressive investments in health and education, region-specific investments, particularly in agriculture, skill enhancement and employment generation, is needed to balance the two sides of the coin – growth and inequality.

(Yash Tayal is a student and Dr Subhashree Banerjee is Assistant Professor of Economics, School of Social Sciences, Christ (deemed to be) University, Bengaluru)