For nearly a century, astronomers have puzzled over the curious variability of young stars residing in the Taurus-Auriga constellation some 450 light years from Earth. One star, in particular, has drawn astronomers’ attention.

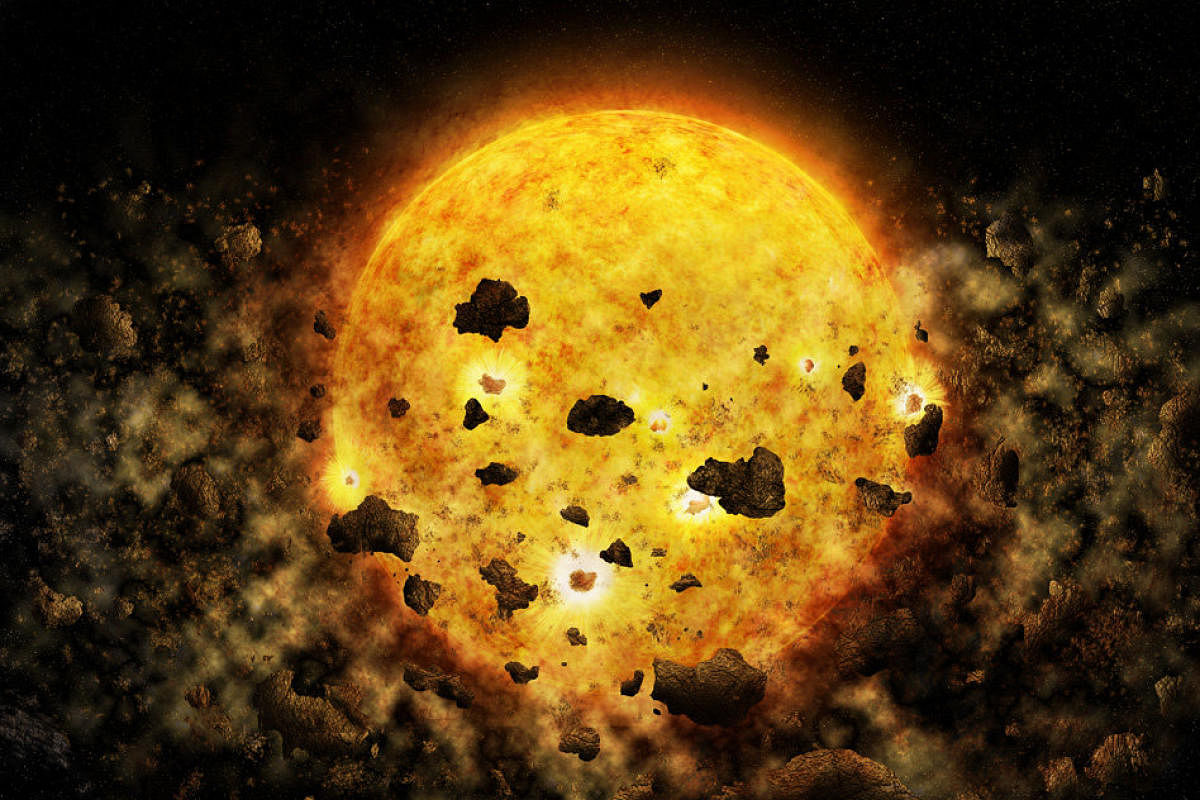

Now, physicists from MIT and elsewhere have observed the star, named RW Aur A, using Nasa’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory. They’ve found evidence for what may have caused its most recent dimming event: a collision of two infant planetary bodies, which produced in its aftermath a dense cloud of gas and dust. As this planetary debris fell into the star, it generated a thick veil, temporarily obscuring the star’s light.

“Computer simulations have long predicted that planets can fall into a young star, but we have never before observed that,” says Hans Moritz Guenther, a research scientist in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “If our interpretation of the data is correct, this would be the first time that we directly observe a young star devouring a planet or planets.”

Scientists who study the early development of stars often look to the Taurus-Auriga Dark Clouds. Young stars form from the gravitational collapse of gas and dust within these clouds. Very young stars, unlike our comparatively mature sun, are still surrounded by a rotating disk of debris, including gas, dust, and clumps of material ranging in size from small dust grains to pebbles, and possibly to fledgeling planets.

In January 2017, RW Aur A dimmed again, and the team used Nasa’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory to record 50 kiloseconds or almost 14 hours of X-ray data. An analysis revealed to researchers several surprising revelations: the star’s disk hosts a large amount of material; the star is much hotter than expected; and the disk contains much more iron than expected— not as much iron as is found in the Earth, but more than, say, a typical moon in our solar system.