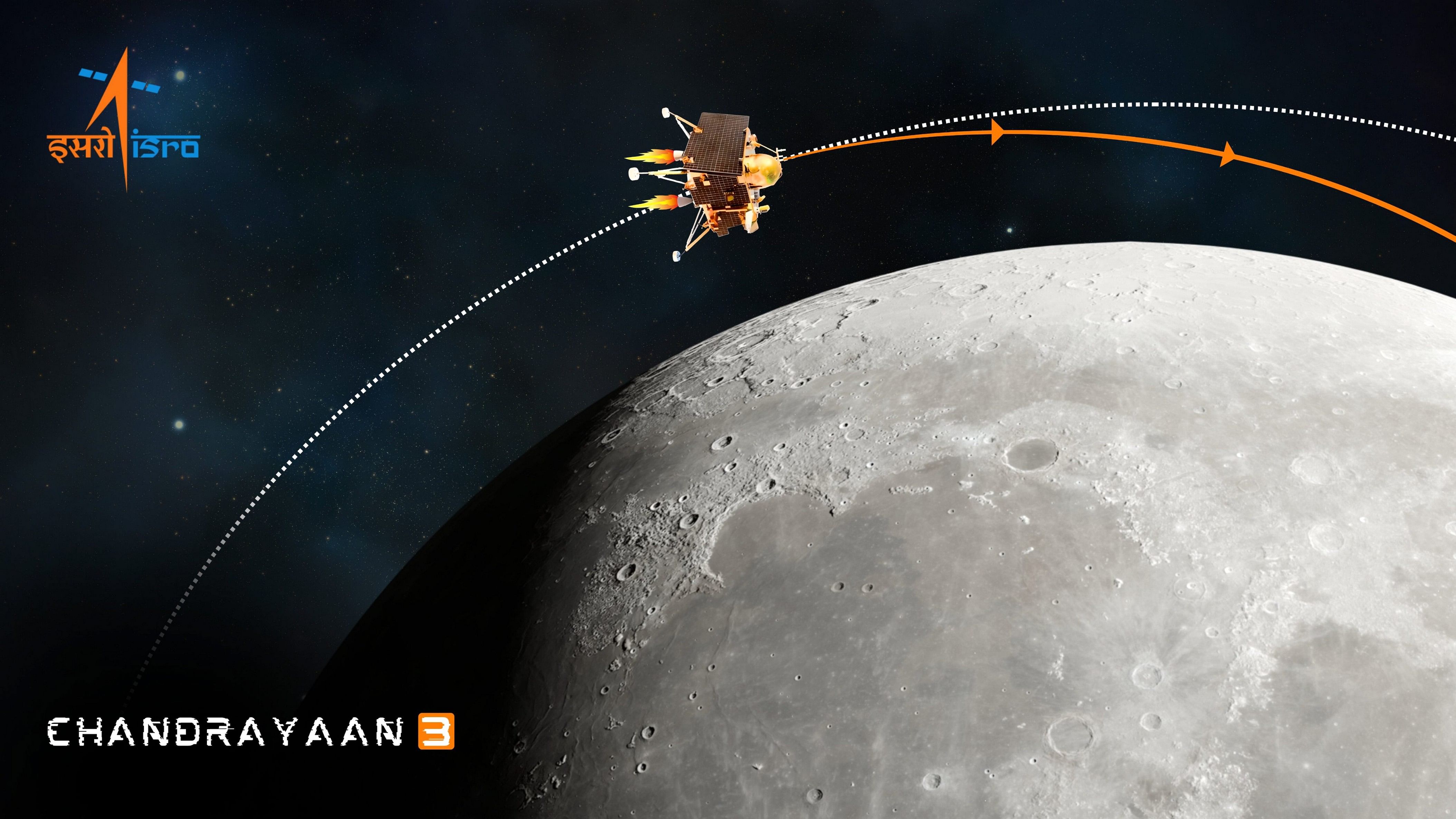

An illustration showing ISRO's 'Chandrayaan-3' after the orbit of Landing Module (LM) was successfully reduced to 25 km x 134 km.

Credit: PTI Photo

Chandrayaan-3, the latest iteration of ISRO's flagship lunar exploration mission, lifted off for the moon on July 14, and is slated to make its descent to our celestial neighbour on the evening of August 23.

The culmination of years of scientific research, and a demonstration of India's growing prowess as a space power, Chandrayaan-3 is expected to succeed where its predecessor failed—to achieve a soft landing on the moon.

With a day to go for what could be a historic moment for India, we take a look at the genesis of the programme and two decades of scientific research that brought India—and ISRO—to this pivotal moment.

A small step for science, a giant leap for India

The origins of the Chandrayaan series of missions goes back over two decades. While the idea for an Indian scientific mission to the moon was floated in the late 1990s, the mission was formally announced by then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee during his Independence Day speech in 2003.

Subsequently, work began on the first phase of the mission—known as Chandrayaan-1—and was completed after five years.

Chandrayaan-1, comprising a lunar orbiter and impactor, was launched on October 22, 2008, and was a massive success.

With a relatively low cost of Rs 386 crore ($48 million), Chandrayaan-1 not only achieved its scientific objectives, but in doing so, also catapulted India into a space power, making the country the fourth in the world to put its insignia on the lunar surface.

Despite being more than 30 years late to the space race, India made its mark.

On the cusp of a breakthrough

Even before the Chandrayaan-1 mission reached the moon, ISRO, along with Russia's space agency Roscosmos, decided to work on the follow-up mission, Chandrayaan-2, which, unlike its predecessor, set a lofty goal of landing on the moon and exploring the lunar surface using a rover.

However, after repeated failures by Roscosmos to provide a lander on time for the mission, ISRO decided to go ahead with the development indepenently.

Consequently, the mission was pushed to 2019.

Even then, technical glitches led to multiple instances of rescheduling, and Chandrayaan-2 was finally launched July 22, 2019.

On September 6, 2019, the Chandrayaan-2 lander malfunctioned due to a software glitch, resulting in ISRO losing communication with it.

Later, then ISRO chief K Sivan confirmed that the lander had a "hard landing", suggesting that it had crashed.

While both the lander and the rover were lost to the unfortunate malfunction, the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter still remains in orbit around the moon, sending back valuable data on our celestial neighbour.

Third time lucky?

The malfunction of Chandrayaan-2 lander led to the development of a third phase—Chandrayaan-3—which sought to achieve the elusive goal of managing a soft landing on the moon.

With the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter still functioning, Chandrayaan-3 was developed with the sole purpose of landing on the moon and exploring the surface.

To that end, the Chandrayaan-3 is carrying only lander and rover payloads, with the lander facilitating the deployment of the rover on the lunar surface.

The chosen site for the landing, the moon's south pole, is significant too: all previous lunar missions, including Chang'e 4 which became the first to land on the unexplored far side of the moon, touched down near the equatorial region, partly because of the relative ease with which such landings can be achieved.

Unlike the lunar poles, the equatorial regions of the moon are more hospitable, offering smoother terrain for landings and temperatures that are conducive for the sustained operation of scientific instruments.

The lunar poles, in contrast, have rugged terrain, and many parts lie obscured in darkness as sunlight never reaches there.

With temperatures reaching as low as minus 230 degrees Celsius and craters stretching for thousands of kilometres, carrying out experiments in these regions is a challenge indeed.

Yet, with challenge comes opportunity, and scientists believe that the lunar poles could contain ice molecules in substantial amounts in craters. Further, the frigid temperatures mean that anything trapped near the poles would remain frozen in time, and rock and soil samples collected from the poles could provide invaluable insights into the conditions of the early Solar System.

Of course, while the prospect of gathering a treasure trove of scientific data is appealing, it all boils down to whether Chandrayaan-3 can succeed where its predecessor failed.

But, there's not long to wait: the probe is slated to touch down on the lunar surface at 6.04 pm on August 23.

To the moon and beyond

Chandrayaan-3 is unlikely to end ISRO's series of missions to the moon, and perhaps more significantly, is expected to serve as a bridge to future missions to our planetary neighbours.

ISRO, in its mission statement, said that Chandrayaan-3 has an "objective of developing and demonstrating new technologies required for inter planetary missions," and already, there are plans in place to launch another mission to the moon in partnership with JAXA, Japan's Space Agency, with the sole purpose of exploring the lunar poles.