Stories have the power to give shape and form to complex realities. Their influence extends beyond our comprehension from the macroworld, to magnitudes as tiny as the nanoscale. The latter is exactly what Pankaj Sekhsaria manifests through his book Nanoscale: Society’s Deep Impact on Science, Technology and Innovation in India. Sekhsaria is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Technology Alternatives for Rural Areas, Indian Institute Technology Bombay.

The book presents four narratives drawn from the nanotechnology ecosystem while engaging the brain with bouts of information. The author unravels the convoluted relationship between science and society in the Indian context and how the world outside the four walls of the laboratory influences the science that happens inside. He manages to maintain the equilibrium between the sociological and scientific dimensions of his narratives, making it an interesting read for both the science, as well as the non-science reader base.

Somewhere inside the world of nanotechnology lie hidden four unique case studies, all eligible candidates for a Bollywood movie, with nanoparticles being the common protagonist.

A romance with ‘Jugaad ’

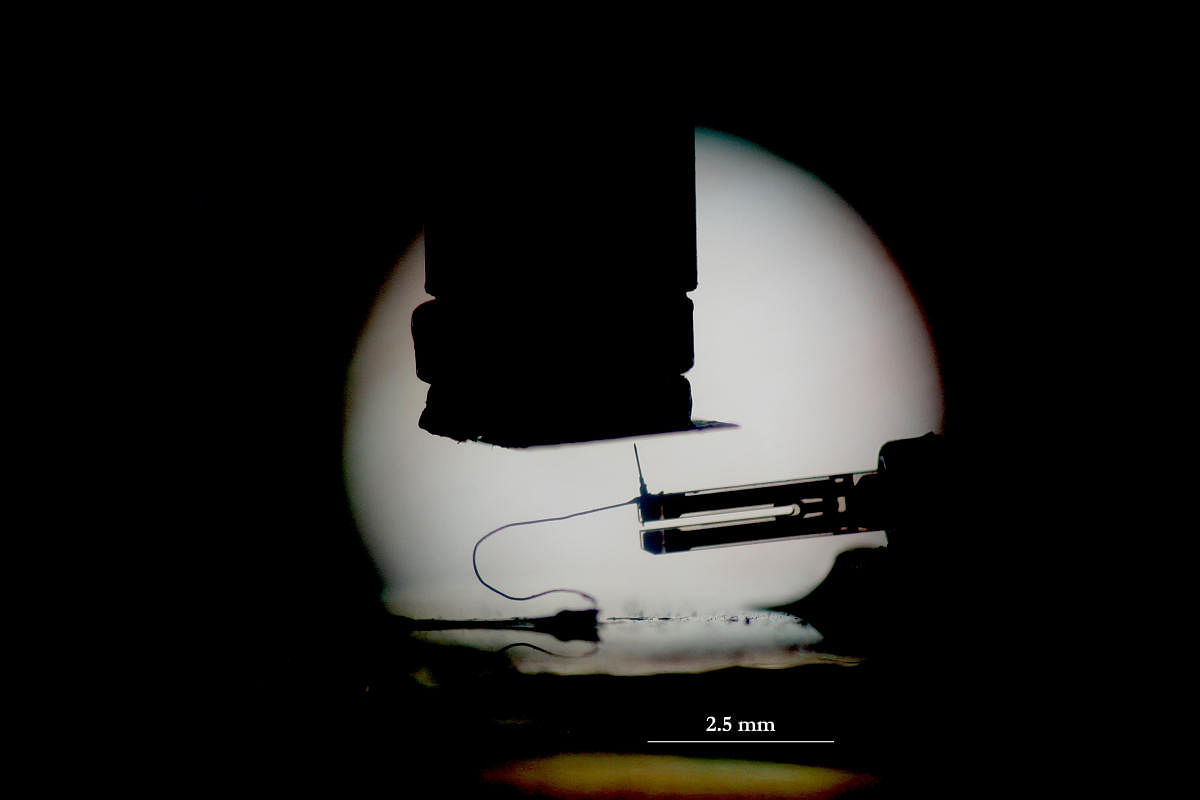

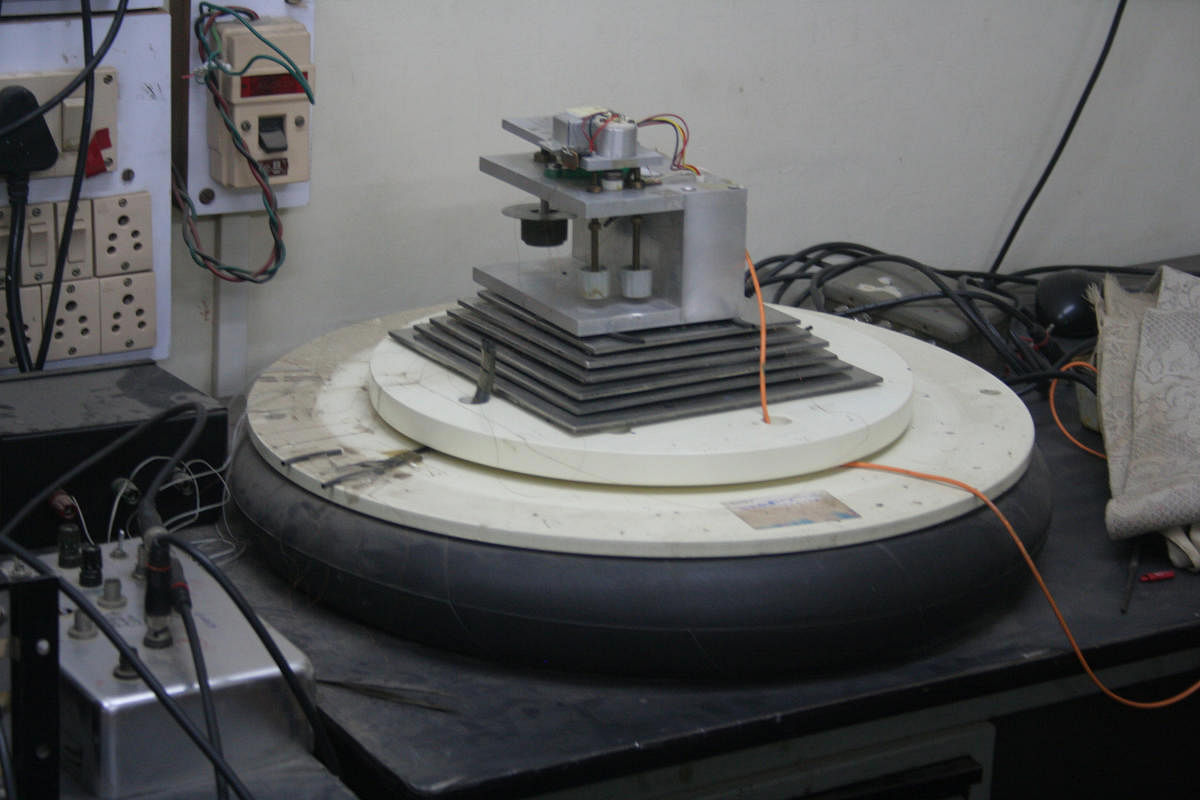

The first story — ‘A Microscope by Jugaad’ narrates in painstaking detail, the making of India’s first scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) by transporting one back in time to 1988. The persistence of Prof C V Dharmadhikari to pursue Mission STM indigenously at Savitribai Phule Pune University amidst severe resource crunch makes for an inspiring storyline.

In this story, Sekhseria also addresses some subsidiary issues that stand as the valley of death for several innovations and hinder the growing culture of commercialising innovations. This, I believe is a point that one needs to ponder on, particularly during the current discussions of ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’, which would help us understand several grassroot problems of the Indian Science, Technology and Innovation ecosystem.

This exciting, inspiring and larger-than-life story sounds perfect for a pickup by the film industry. However, unlike typical Bollywood plots that end happily ever after, this case reveals a sad ending. The mention of the unceremonious dumping of a masterpiece as marvellous as the STM at the end of Prof C V Dharmadhikari’s career for want of precious laboratory space leaves the reader with a lump in the throat.

The book highlights the role of Jugaad in the making of STM and doesn’t shy away from acknowledging its weight in the Indian innovation ecosystem, calling it both an “instinct and inspiration.”

The hero falls

In the third story, the reader is transported to the film city of India —Hyderabad that also hosts the International Advanced Research Centre for Powder Metallurgy and New Materials. The researchers here successfully developed an economic solution called ‘Puritech’ to ensure affordable water filtration by disinfecting drinking water using ceramic candles impregnated with silver nanoparticles.

Just when it seems that this is an all-happy story, there comes a twist. Although ‘Puritech’ seemed to be an innovation that could be celebrated owing to its low cost, it was not commercialised as it was priced marginally above the already existing ceramic candle filters.

It was easily trampled by big brands who offered cheaper alternatives. This chapter, titled ‘Water purification with the nanosilver edge’ reveals the bitter truth that the technology development cycle remains incomplete without well-outlined business and commercialisation strategies.

A murder story

The plot continues to be set in Hyderabad, at the L V Prasad Eye Institute where nanotechnology finds applications for treating infants suffering from retinoblastoma, a common malignant eye tumour.

The chapter ‘Nanotechnology for the treatment of Retinoblastoma’ brings to the fore the Catch-22 situation that doctors like M Javed Ali and the patient’s family are in.

The doctors here need to take on additional responsibilities — that of a scientist, counsellor and social activist while dealing with parents who value their daughter’s marriage over her life. This story throws light on the dark reality of how societal pressure to get daughters married prevents parents from opting for a lifesaving surgery that requires the removal of an eye. In a society that does not accommodate disability, he aptly highlights the ingrained gender bias that plagues the fabric of society.

These well-documented narrations bring to the forefront several unheeded, yet key issues that affect the lives of Indian nanoscientists, researchers, innovators and technology developers.

Using the Social Construction of Technological Systems approach that is generally used to study the history of technology, Sekhsaria analyses how society percolates into the heart of the laboratory.

He explores various aspects that determine the relationship between the social and scientific tenets, embedded in science research and development.

This unique sociological analysis of nanotechnology points to the need for more emphasis on innovation that can be fostered by venturing beyond the current siloed approach in education. It indicates the need for a multidisciplinary approach that considers societal and cultural issues to address the root of systemic problems.

(Jenice Jean Goveas is a Postdoctoral Policy Fellow, DST-Centre for Policy Research, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru)