Awe-inspiring sights of comets and eclipses are etched in the memory of a viewer irrespective of age, sex and circumstances. Thus sculptors wonderstruck at the sight of the eclipsed sun as a black disc in the sky would immortalise their wonder when they have an opportunity later. Artists are no different. There is a well-known example from Europe. A comet decorated the sky in 1301, only to be immortalised into the famous painting called “The adoration of the Magi” two decades later. Four hundred years later Edmond Halley looked back for records of the comet and found that the “star of Bethlehem” was one apparition of the comet. The mission to visit comet Halley in 1986 was named Giotto to honour the artist Giotto di Bondone.

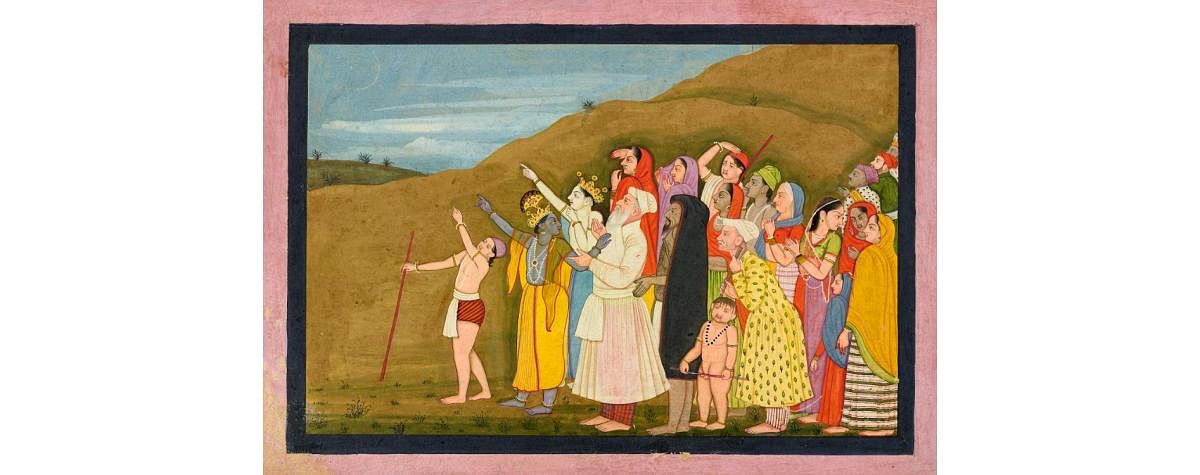

Artists from India predominantly chose mythological themes so popular that one don't need any reference to guess the episodes. The episodes of Ramayana and Mahabharata so also the stories of “Leela” featuring Lord Krishna from Bhagavad Purana. One exception surfaced recently when the Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art released a rare piece of art on its blog. The painting is rooted in mythology, from Bhagavad Purana, and is dated to the late 18th century. The Islamic influence on the costumes is striking and is called Pahari artwork, from Kangra.

The scene depicts Krishna and his family — all pointing to the blue sky, amazed at the sight. The artists at the museum produced the object of attention having zoomed in and touched up the blue sky. It looks like a thin crescent moon. The associated description also narrates the episode — Krishna’s family with Akrura and others went to Kurukshetra for a holy dip on the occasion of a solar eclipse. Therefore the awe-inspiring sight is that of the eclipsed sun.

Chapter 82 of the 10th volume of Bhagavad Purana begins with this description of the journey to Kurukshetra. The uncertainty in the date of the origin of the Bhagavad Purana prevents us from timing the episode accurately using the eclipse; however, another interesting aspect was unveiled which put an end to the criticism on the non-availability of records of a total eclipse from India.

The admiration of the celestial spectacle and possible associated conversations are very emphatically expressed on the faces of all the characters. This leads us to infer that the artist himself would have witnessed this magnificent sight of a totally eclipsed sun and therefore expressed it so efficiently at the right opportunity, though the Purana does not specify that it was a total eclipse.

Narrowing down a date

The artist is Nainsukh. A search by historian Prof Kavita Singh of Jawaharlal Nehru University revealed the identity of Nainsukh’s family. They were well-known for rendering the episodes from Bhagavad Purana; these paintings have been preserved in many museums across India.

The family lived in the second half of the 18th century. This provides the clue to search for the eclipse which the artist would have seen. 'Pahaari’ originates from ‘pahaad’, the hilly slopes of the Himalayas which comprise Himachal Pradesh and parts of Punjab and Kashmir today. Thus we would have to search for possible eclipses with shadow sweeping across this region.

The search leads us to four eclipses between 1730 and 1800. Two of them were visible as partial eclipses. Another, in 1763, was indeed a total eclipse with the near-total phase visible from Kangra. However, that was in the late afternoon. We now can use the elevation of the Sun above the horizon as another key. It was quite low — meaning it was just before sunset or after sunrise. This helps us come to the conclusion that the eclipse was on September 5, 1793. The eclipse occurred late in the evening and they would have seen the setting of the eclipsed sun.

As I gather after witnessing four total eclipses, during totality, the sky gets completely dark, except near the horizon. The charm of the pearl-like dots along the rim called Bailey’s beads and the diamond ring are unforgettable. However, this is not the case with annular eclipses. The sun looks like a bright ring and the sky does not go dark. The scene depicted in the painting thus appears to be one of an annular eclipse rather than a total eclipse. The 1793 eclipse was an annular eclipse.

Thus Nainsukh immortalised his sighting of the eclipse in this beautiful piece of art. This gives us hope that a rigorous search for similar renderings of celestial wonders will fill the lacuna of such artworks from here.

(The author is with Jawaharlal Nehru Planetarium, Bengaluru)