It had a reputation for unreadability. As its author walked by, a student at the University of Cambridge in England was said to have remarked: “There goes the man that writt a book that neither he nor anybody else understands.” Its hundreds of equations, diagrams and obscure references didn’t help, nor that it was written in Latin, the scholarly language of the day.

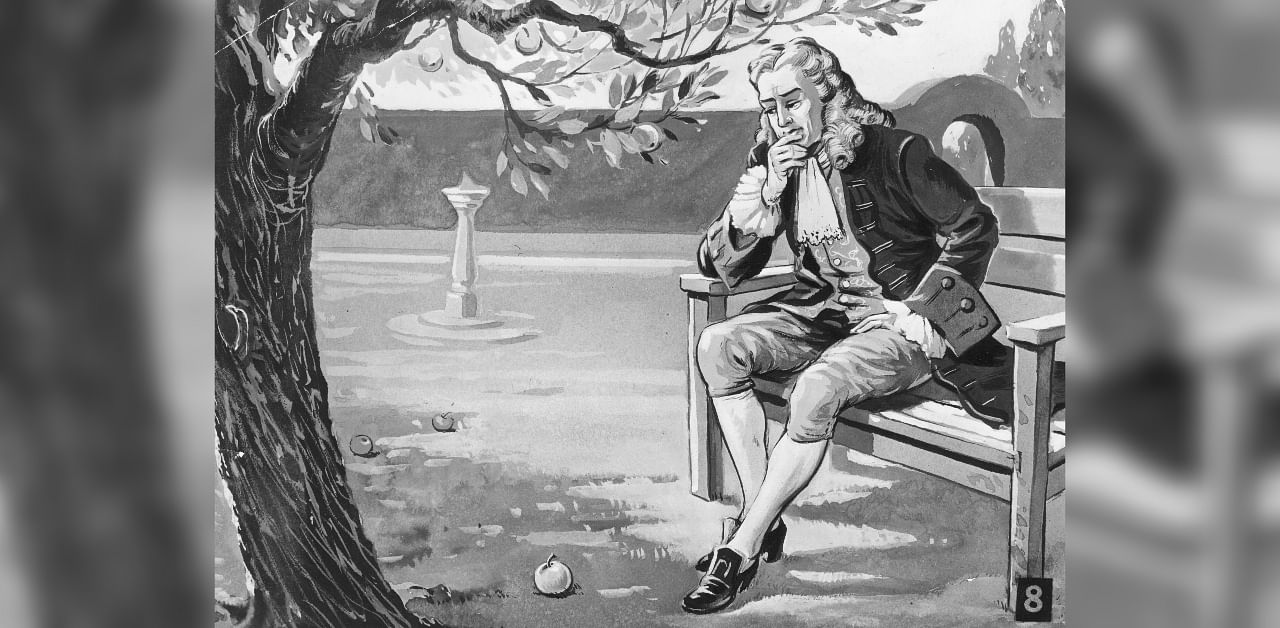

Isaac Newton’s “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica,” or Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, published in London in 1687, nonetheless went on to become a scientific colossus. It unlocked the universe with its discovery of gravity and laws of planetary motion, and laid out a method of inquiry that became the gold standard. It was known as simply the Principia, the Principles.

Now, historians have discovered that the first, limited edition of the seemingly incomprehensible book in fact achieved a surprisingly wide distribution throughout the educated world.

An earlier census of the book, published in 1953, identified 189 copies worldwide. But a new survey by two scholars has found nearly 200 more — 386 copies in all, including ones far beyond England, in Budapest, Hungary; Oslo, Norway; Prague; Zagreb, Croatia; the Vatican; and Gdansk, Poland.

Mordechai Feingold and Andrej Svorencík, writing in the current issue of Annals of Science, a quarterly journal, said the unexpected total suggested the book had “a much larger print run than commonly assumed” as well as “a wider, and competent, readership.”

Feingold is a professor of the history of science and the humanities at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, and Svorencík, his former student, is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Mannheim in Germany.

The two scholars, by analyzing ownership marks and notes scribbled in some of the books, as well as related letters and documents, found evidence contradicting the common idea that the first edition interested only a select group of expert mathematicians.

They said the finding also implies that current historians have underplayed the early impact of Newton’s ideas. It necessitates, they write, “a major refinement of our understanding of the contribution of Newtonianism to Enlightenment science.”

How do the scholars know where the volumes were during the Enlightenment? Couldn’t the books have subsequently found their way centuries later to such places as Gdansk or Zagreb? The answer, they said, was finding clues in the books themselves, as well as library records that helped establish their provenance and later movements. Their paper in the Annals of Science, nearly 100 pages long, sketches out the known travels for each of the 386 books over the ages.

In a Caltech report on the discovery, Svorencík said the hunt had its origin in a paper he wrote for Feingold. The student received a master’s degree from Caltech in 2008.

Svorencík grew up in Slovakia and wrote in his Caltech paper about the Principia’s distribution in Central Europe — in particular, the Habsburg Empire. His main question was whether first editions could be traced to his native country. “The census done in the 1950s did not list any copies from Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland or Hungary,” he recalled. “This is understandable as the census was done after the Iron Curtain descended, which made tracing copies very difficult.”

To Svorencík’s surprise, he found many copies. Feingold then suggested they turn his project into a systematic search for first editions. Over a dozen years, their endeavor turned up some 200 previously unidentified copies in 27 countries, including 35 in Central Europe.

The scholars also found lost books. A bookseller in Italy was discovered to possess a copy stolen from a library in Germany half a century earlier.

In an interview, Svorencík said a big surprise came early in the hunt during his sweep through Germany. “The previous census reported only three German copies, but I found nearly 20,” he said. The finding pointed to “substantial gaps in the existing record.”

The hardest part of the search, he added, was gaining access to privately owned copies, as well as obtaining financial support that let the scholars travel to libraries and places where they could personally examine the first editions and extract vital information.

Even so, Svorencík said, the long hunt gave him the opportunity to personally inspect a number of the extremely rare books. “Each copy that I have examined is unique,” he reported. “Copies differ in their binding, condition, size, annotations, printing differences and even scent.”

The scholars hope that their search, which they call preliminary, will produce new clues about other copies tucked away in libraries, as well as with book dealers and private owners.

“We decided to publish our census as a means to reinvigorate the project,” Svorencík said in the interview. The goal now, he added, is to “alert librarians and private owners to the census in hope to receive information regarding other unknown copies.”

First editions of the Principia, the scholars say, today sell for between $300,000 and $3 million on the black market and at auction houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s. They estimate that the book’s first edition consisted of some 600 and possibly as many as 750 copies — hundreds more than the 250 or so that historians had previously assumed.

“We are still searching for copies,” Feingold said in an email. He called the hunt “exciting and laborious” and, like Svorencík, said he hoped news of their discovery would help generate new information about extant copies of the scientific masterpiece.