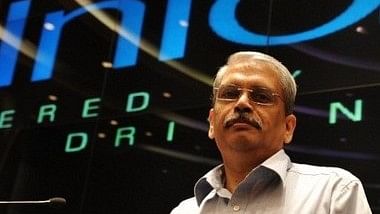

Kris Gopalakrishnan

Credit: DH Photo

The Infosys Science Foundation (ISF) on Wednesday announced winners of the Infosys Prize, across six categories. ISF president Kris Gopalakrishnan notes that the awards, in their 15th year, have grown in stature. In a milestone year, the foundation is evaluating progress and restating two core objectives of the $100,000 prize – recognising scientists doing impactful work and inspiring the youth to pursue careers in science. The ISF head spoke with DH on the prize, the significance of rewarding scientists in a country that does not celebrate them enough, and what makes research here an exciting, challenging prospect. Excerpts from the interview:-

At 15, what does the Infosys Prize signify, in terms of objectives and impact?

The prize was launched to promote important research, support world-class scientists and encourage youth to take up careers in science. It is also a way to show that society appreciates these scientists, by organising their lectures in schools and colleges. Over the years, we have had 92 winners and many of them have gone on to do significant work and win other major awards. The evaluation of where and how we can improve will continue; we want to make sure that our goal of creating icons and recognising impactful science is sustained.

How do you assess the infrastructure for scientific research in India?

In talent, we are second to none. Our researchers are trained in the best of universities. The cost of doing research here is low and access to technology has not been an issue. There is a problem with the money, though. India invests about 0.7% of its GDP in research. I would like to see it at around 3%, with the industry and the government contributing equally. In terms of publications, some of our institutions are doing reasonably well but we are falling short in translating this research, from lab to market. The focus has to be on creating products and technologies we can own and monetise. We need to create more startups and shift to ambitious, mission-mode programmes like the ones taken up by Isro.

Has policy been effective in enabling this shift?

I don’t see this as a policy issue. India is a developing country and its problems are, largely, of a developing country. Our priorities today are primary education, quality healthcare, food, and jobs. These priorities will shift over time, as we progress to become a middle- or high-income country.

What could make scientific research a more rewarding career option?

We need to ensure that the PhD students, post-docs, faculty and researchers are paid well. Today, they feel that they are sacrificing something if they don’t join the industry. They should not feel that they are losing out by choosing a career in science. There is some uncertainty about funding for research. If we have guaranteed funding for a specific number of years, some of this uncertainty can be removed. We need exemplars; we need to celebrate successes like Chandrayaan-3 that can inspire our youth to take up careers in space.

How is India placed in translating scientific research to applications of social significance?

Research only comes up with inventions. Funding is crucial in transforming them into products or technologies society can use. Between the lab and the market, specifically between TRL (technology readiness level) 3 and TRL 7, there is very little funding. The research funding stops at 3 when the paper is published; the VCs do not invest before level 7 or 8. This is where the government, industry and philanthropists can come in (and plug the funding gap).

The National Research Foundation is coming up, with a Rs-50,000 crore budget over five years.

The foundation is a good idea. We need a coordinated effort to encourage research and we need to look at larger programmes. There are programmes that are very strategic to the country, like the National Quantum Mission. Having a deep research capability is both economically and strategically important for the country.

Are our efforts to build scientific temper in conflict with narratives that trace science to traditional knowledge?

India’s knowledge system is experiential and observational. It is amazing that so much wisdom exists in our civilisation but a lot of it is also lost. There is a need to preserve this knowledge – I prefer calling it classical knowledge – for the future. Then, we need to look at ways to place them in the present context. Science is evidence-based; we can use the tools of modern science to understand how it (classical knowledge) works. That will mainstream it and, probably, increase its acceptance.