In 2010 or thereabouts, I heard from a friend about a place in BTM Layout teaching fitness. I had no clue the school was called a dojo, and tai chi was what it taught. My son, then 10, was hooked to cartoon shows on TV, and was excited about going to a place where he would learn

martial arts.

The motivation, for me, was something else. For six years, I had been battling a severely painful condition that the doctors had diagnosed as diabetic neuropathy. My skin felt like it was on fire round the clock. The many neurologists I visited offered me a dire prognosis, telling me it would progressively get worse. I had to learn to live with the burning sensation. The medical term for such unpleasant sensations is paresthesia. All I was reading then was medical literature. Some doctors said I should prepare for loss of motor functions. In other words, prepare for a future in a wheelchair. Despairing, I was ready to try anything that would make me feel better.

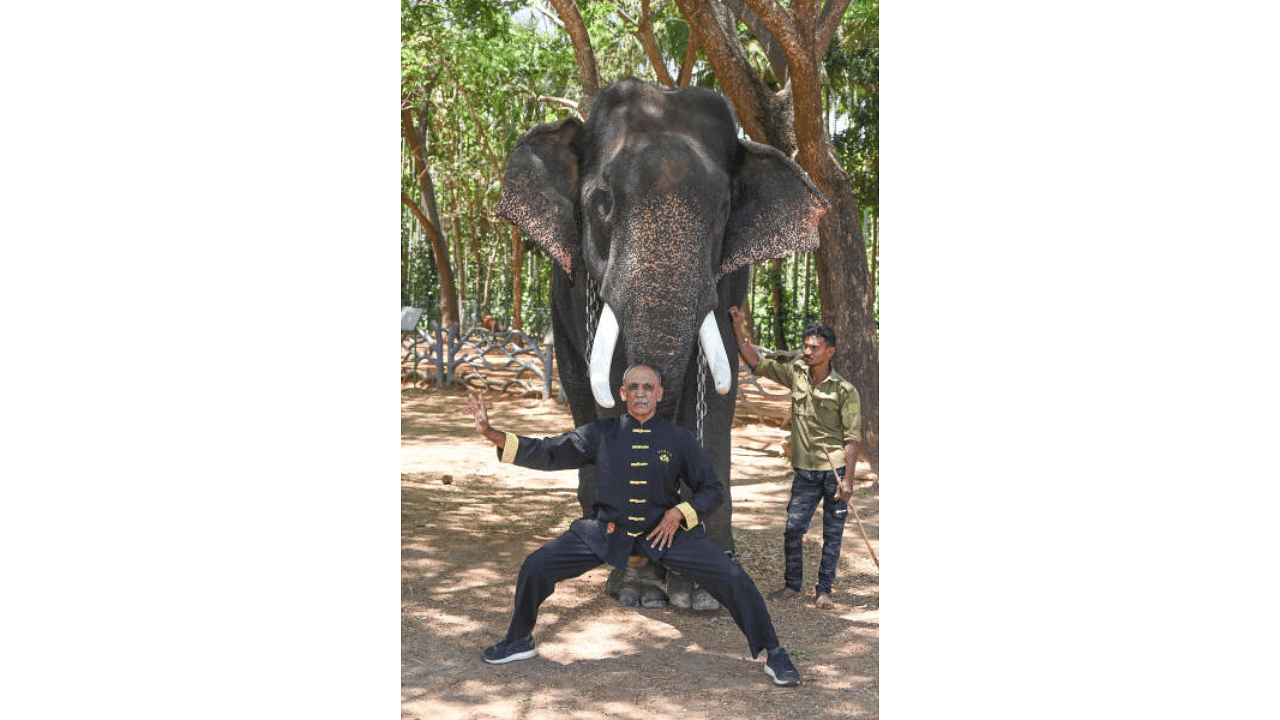

That was when I met Shifu Avinash. I started attending his classes, which then lasted about two hours. In the initial months, I was exhausted and ravenous after each class, and ate twice as much as my normal quantity. I have been a part of the dojo for 12 years. Over the years, I got to know more about Avinash, and his story was right out of an action thriller. It was cinematic, and left us incredulous. It was a long time before I could even discern the many interweaving patterns in his saga, with martial art segueing into spirituality, and discipline

morphing into boisterous fun and love of animals. How I got to recover and feel better is a thread I will pick up later, but first, let us cut to Avinash’s childhood.

Karate beginning

As a schoolboy, Avinash was fascinated by the stunts he saw in films. He remembers jumping around excitedly after watching films such as ‘Superargo Versus Diabolicus’ (1966) and ‘Kiss Kiss Kill Kill’ (1966). His fascination for fight scenes inspired him to write admiring letters to a renowned exponent of martial arts who lived in Chennai.

The master took a liking to him. He was not easy to meet, but Avinash made trips to Chennai, and sometimes, the master visited

Bengaluru. It was the MGR vs Karunanidhi era. The karate master had learnt from distinguished martial artists in Japan, and he was, in turn, teaching thousands of students in India. Under his fond tutelage, Avinash, still in school, picked up some of the most difficult skills characteristic of the Japanese martial art, the flying kick and the round kick being just two of them. He had also learnt that training meant accepting the master’s eccentricities — he could be excessively affectionate or whimsical and unreasonable. One day in Chennai, he sat and knotted yellow ties with polka dots for a whole

film crew.

In the mid-70s, Avinash came in touch with many Japanese masters, and got the opportunity to learn from them. He made trips to Japan, and during his training, got a glimpse of what tai chi practitioners were doing. He had trained in hard martial arts, and was fascinated by what tai chi offered: gentleness and power. He then trained under John Wilson in Canada and Ueda and Masayuki in Japan.

In subsequent years, his curiosity took him to Chenjiagou village in Hunan province, where tai chi is said to have originated. He struck up a close bonding with Chen Zhaosen, grandmaster of the Chen style of tai chi, and direct descendant of the founder of the style Chen Wangting. Over the past decade, Avinash has made frequent visits to the village to learn under the master.

Back in India

Not many in India know of tai chi — it is a somewhat esoteric art. So when people ask students of Shifu Avinash what they are learning, they often say, ‘Chinese yoga’. Tai chi, like yoga, is ancient, and it is a wellness art. Patanjali, who wrote the famous yoga sutras, is said to have lived between the 2nd and 4th centuries, while tai chi is believed to be at least 2,500 years old. Books on tai chi classify it as an internal martial art, and hence useful for health, wellness and healing, as against the harder external arts oriented to self-defence and combat.

Many forms of martial arts, including indigenous ones such as Kalaripayattu, are practised in India, but the most popular are the ones celebrated in Hong Kong and Hollywood films. Bruce Lee is an iconic figure, and after him came Jackie Chan. Avinash has watched their films, and finds some of them inspiring. “In reality, martial arts are not so dramatic, though,” he says, chuckling at some of the more ludicrous representations. Tai chi is subtle and effective, and its movements are economical, he says. His favourite Bruce Lee line is “Be like water”.

Tai chi seeks to work with qi (pronounced ‘chi’), the vital energy in the body. “Qi moves like a wave,” says Avinash. “It draws energy from the universe and delivers it where it is required.” His first encounter with an unassuming tai chi practitioner was in Japan. A skinny, elderly man was sitting in the backyard and chopping firewood with a sword. His strikes were precise and effortless, and the hard wood was cracking without resistance. “It was tai chi at work,” Avinash says.

In many ways, Avinash is a product of the ‘70s. He was witness to the exuberant pop culture of the era, and plunged into the exuberance of the emerging martial arts culture. He soon made a name for his skill, and was called in to choreograph the fights for a Zeenat Aman film. He slowly moved away from it, finding his moorings in the more classicist practice of tai chi.

Over the years, Avinash has trained people in various settings, government and private sector. At his demos, he frequently runs into sceptics, especially among those who have practised boxing and the more aggressive sports. It takes a pushing challenge, where he resists their brute force, to convince them about the gentle power of

tai chi.

Why so slow?

In recent months, Avinash’s students have put out some videos on

YouTube. They feature some stunning feats. The series is called ‘Qi is Key’. In one video, he rides a motorcycle standing, and slices apples and watermelons flung in the air. In another, he glides on sticks placed on the floor as he slices apples flung in the air. He attributes his aiming, balancing and coordination skills to tai chi. “I see everything in slow motion,” he says. Metaphorically speaking, he says, this shows that when life throws multiple things at you, you must learn not to panic. Practise being calm in the storm, he tells students.

Tai chi is often mistaken for a slow, undemanding art practised only by elderly people. Not true, says Avinash. The youngest student at the dojo, Veera Jain, is now 10. She has been around for five years. But is tai chi just a dreamy, dance-like art? No. Fa jin, an integral part of tai chi, is about deploying energy to disarm an opponent. “The extraordinary power of fa jin is the ability of a practitioner to send an opponent sprawling with a sudden application of force using very little overt movement,” writes Jess O’Brien, acquisitions editor, in a foreword to the book ‘The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi’ by Bruce Frantzis.

As in music, where students practise their scales slowly and then graduate to speed, so also in tai chi--slowness prepares students for speed. Milan Kundera, in his novel ‘Slowness’, writes, “There is a secret bond between slowness and memory, between speed and forgetting.” What is learnt slowly stays. “You can say tai chi is age defying because you get better with age, since it is mostly qi and not the muscles we use. Qi becomes stronger with practice, unlike muscles,” says Avinash.

Body wisdom

A student once came up to Avinash and said he was lacking in confidence, and couldn’t match up to his colleagues in his English language skills. He expected Avinash to tell him to sign up for an English speaking course. Avinash told him to take horse-riding lessons, or do something that would make him more outgoing. “The body has its own intelligence, and we should let it do its work without the mind getting in the way,” Avinash later said, explaining how a fitter, more confident body would have transformed his student, whose language skills were good enough.

He combines tai chi with other practices such as liang gong and qi gong. The power of qi, he explains, can be harnessed for anything, including work and play. Among his students are golfers and cricketers, doctors and dancers.

Avinash loved running, and had taken part in extreme sports in his younger days. After he switched to tai chi, he won an international competition despite his severely injured knees. On another occasion, he suffered a high-voltage electric shock, and survived. He attributes the resilience to his consistent practice of tai chi.

Coming back to where we began, I was down and out when I began going to the dojo. My personal life had become deeply traumatic. A Mumbai-based newspaper I had been working for had just folded up. I had seen a dear aunt being run over by a train, and my efforts to take her to hospital had run into the most unbelievable hurdles. The loans I had taken for a pet project weighed on me. For my neuropathy, I continued to consult doctors, traditional and modern. In my desperate search for relief, I stumbled on a report about a surgeon who had taken part in a clinical experiment to alleviate the pain of neuropathy.

I went looking for him from Bengaluru to Mumbai. He was proud to be sought out. He said surgeons were placed low in the medical pecking order, but they were capable of great feats. My hopes went up. When it was time to leave, I asked him if he could perform surgery on my legs, as he had done during his experiment. The pain had engulfed my entire body . “I can do anything. I can cut your left leg and attach it to your right, and cut your right and attach it to your left,” he said. This was a megalomaniac, and he had pushed me to despair again.

The activities at the dojo checked my brooding, and made me physically active during the weekends. It took a couple of years for the gloom to lift. The pain receded slowly. My tai chi skills remain rudimentary, but people who know me will tell you I am more cheerful today than I was a decade ago.