The Western Ghats are renowned for their scenic beauty and have been identified as an important global biodiversity hotspot. In this context, the recent viral footage of nearly 500 trekkers thronging to trek up the Kumara Parvatha peak in Karnataka was shocking. The Kumara Parvatha is a challenging trek through the lush, moist, deciduous, and evergreen forests. As one nears the peak, the trail leads through the unique “Shola” forests, or the upper montane evergreen forests, characterised by stunted trees, leading into hilltop grasslands. Once atop the peak, the expansive vistas of the undulating Western Ghats make the long and challenging trek worthwhile.

Many parts of the Western Ghats are protected in the form of sanctuaries, national parks, or tiger reserves. The notion of conservation has multiple core values, and one of them is aesthetics. Walking amidst nature enables us to appreciate the beauty of the bubbling stream, the falling leaf, the rotting log, or the towering tree. Everyone, from philosophers to contemporary mental health experts, says that walking is a good thing. It keeps us healthy and clears our minds. Trekking is an extension of walking; it is coupled with adventure and is often arduous.

However, hordes of people showing up to trek on a fragile forest path are at odds with the value of conservation for aesthetics. The Karnataka Forest Department immediately stepped in and imposed a ban on trekking across Karnataka, albeit temporarily. A ban in one place will redirect people to other fragile areas and will not work. A ban on trekking is, in its essence, in contravention of why we establish conserved or protected areas. There must be a paradigm shift in how civil society values nature and how the administration deals with this persisting problem of large-scale eco-tourism.

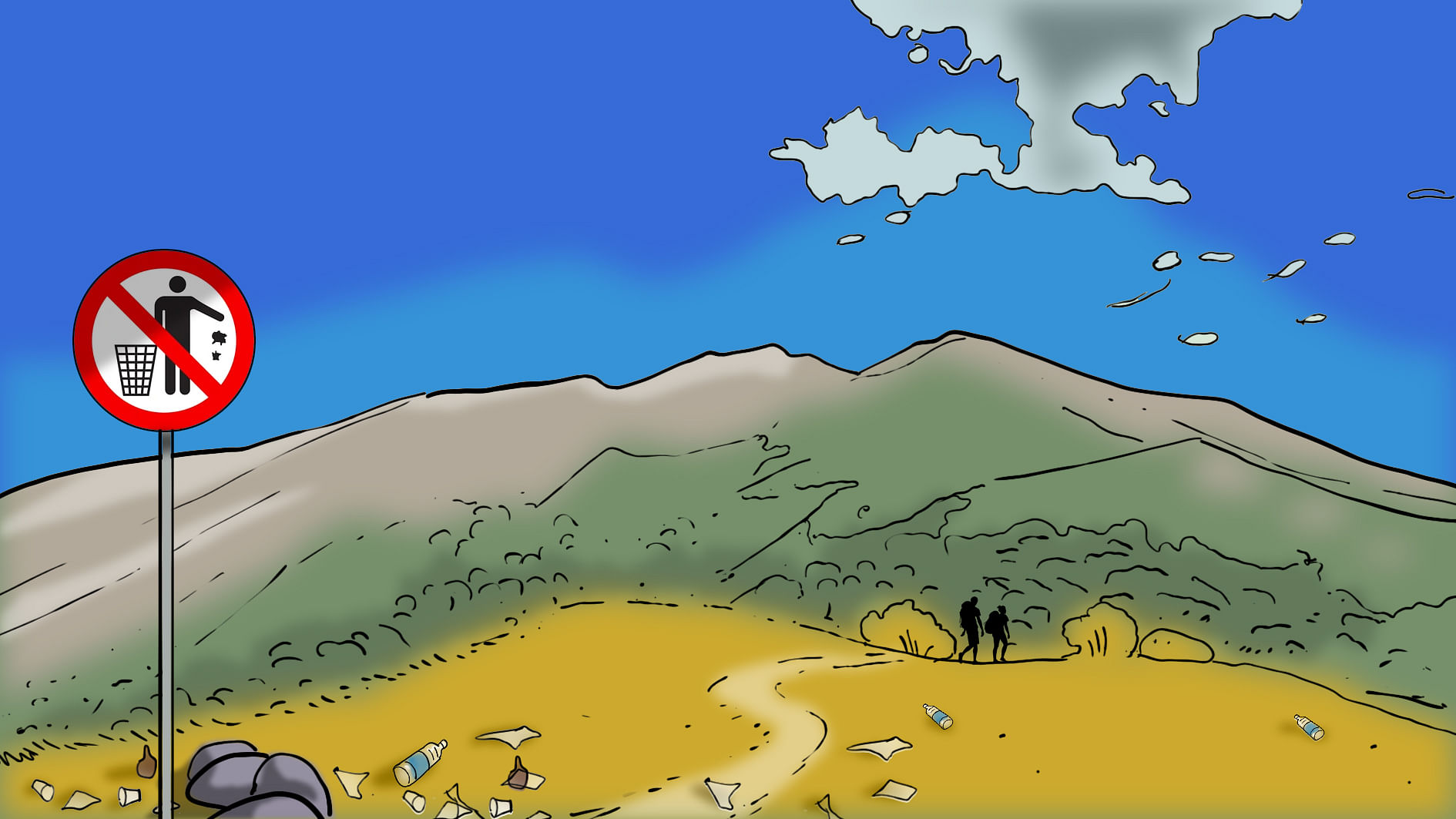

Trekking can have numerous impacts on nature. Most common among them are vandalism or trampling of vegetation along the way. Then there is littering. Most trekking paths across the state are littered with plastic, despite people being made aware of the hazards of plastic use. There is also the risk of forest fires when a lit cigarette butt is flicked into dry forests. Alcohol consumption and littering with glass are also huge problems in most natural areas. Apart from being an eyesore, the shards of broken glass can seriously injure humans and other wildlife who don’t always perceive glass.

People also indulge in seemingly innocuous practices such as stone stacking, which ruins habitats for insects and other invertebrates. Another risk is the spreading of alien exotic plants into forests,

with trekkers inadvertently carrying seeds stuck on clothing or in their shoes and

dispersing them.

There are also active impacts, such as disturbing wildlife. People shouting or playing loud music while trekking are now widespread practices. People also indulge in feeding wildlife, which is bad for the animal and increases the risk of being attacked by the animal. All of this will interfere with the foraging or feeding activities of wildlife, eventually affecting their survival. While impacts on nature are plentiful, they are magnified when a trekker is lost or injured, and search and rescue parties are sent in to comb the area. The lack of route maps or a well-marked trail further confounds these effects.

In an ideal world, people choosing to go on a hike would be a good thing. However, in India, this would mean hundreds, if not thousands, of people. Unfortunately, post-Covid, there has been a drastic increase in the number of people going out into nature, earning the moniker ‘revenge tourism’ as well.

Trekkers have various motivations. They could simply want to exercise or go on a hike because everyone on social media is doing it, or they might just want to step away from mundane city life. Every trekker is different, and while many of them may keenly observe nature, there could be others who do not even realise that they walked past a plant or an animal that is found nowhere else on earth.

What’s an ideal trekking path?

In 2011, I travelled to New Zealand for a conference on conservation biology. Post-conference, I visited the South Island and hiked across the rugged mountains on the famous “Routeburn” track nestled within the iconic Fiordland National Park. At a time when the world was not as connected as today, I recall having booked permits to go on this trek months in advance, sitting in Bengaluru. The trails were extremely well-made, marked, and managed. There were maps at the start of the trail, clean restrooms, and drinking water stations. The trails followed the contour of the mountains and were maintained to keep them stable, with plenty of markers to keep trekkers from venturing off the trails. I began hiking alone, but soon a typhoon kept me company. Yet, the trails were clear of water, and there was no gully erosion created by the flow of water. Midway through, they had a dormitory where one could spend the night and continue the hike. There were board-walks in areas where the trail ventured into fragile forests and multiple stop-over points to relax, slow down, and observe nature.

In each habitat, there were sign boards to keep an eye out for a bird or a plant. They had also taken immense care to ensure no invasive species reached the island nation by sanitising shoes at the airport itself! The Department of Conservation, which manages forests in New Zealand, has published clear guidelines on how tracks and trails should be managed. Many of the guidelines revolve around civil engineering issues with a strong connection to conservation. These could be adapted to our needs and implemented as well.

The road ahead

The administration here in Karnataka should use this opportunity and the ban to revisit some of the values and ways in which we manage trekking in the state. While the permit system is good, there must be conscious steps to make it equitable and accessible. The funds collected from the permits should go into maintaining the paths, ensuring that damage to the forests is minimal, and making the patrolling staff permanent and paid well. The undergraduate training in forestry should make a paradigm shift towards a holistic approach to managing forests, and students should learn about aspects of civil engineering with an explicit focus on trail management. The use of plastic and alcohol could be reined in by strict frisking. Plastic littering can be prevented by making trekkers pay a deposit and marking the plastic items. The deposit can be returned upon bringing back the plastic with them.

A strict cap on the number of trekkers should be based on carrying capacity analyses. Where possible, trekking paths could be co-managed with the local community, so they too can benefit from tourism and gain a sense of ownership.

On a philosophical level, there is also a need to consciously slow down the trekkers from a mindless race to the top and observe the intricate beauty of biodiversity instead. Rao Jodha Park in Rajasthan is an excellent example of how to mindfully curate nature trails to enhance the learning experience. In our state, the Karnataka Forest Department tied up with the Department of Tourism in 2014 to create a pool of “eco-volunteers” who were trained by researchers and naturalists to be able to appreciate nature. This programme should be nurtured by including members of the local community, and the trained volunteers could double up as nature guides or assist the park rangers to manage our fragile forests and ensure the dictum “take nothing but memories and leave nothing but footprints” is followed in word and spirit.

(The writer is a faculty at ATREE. Views personal)