Credit: Special Arrangement

Let me first tell you what epigraphy is. We in India aren’t as excited about this critical field of archaeology as we are about explorations and excavations.

Epigraphy is the study of writings engraved on stone, metal, wood, shell, pottery and other hard surfaces. The writings are called inscriptions or epigraphs. Palaeography is an allied competency — it concerns the study of ancient scripts.

The discovery and decipherment of inscriptions is challenging and expanding our knowledge of history. Thanks to an inscription stone found at a temple in Begur, a village off the Bengaluru-Hosur highway, we now know that a settlement called Bengaluru existed about 1,000 years ago. This pushed Bengaluru’s history further back than the ‘boiled beans’ legend suggests. Many believe Kempegowda I founded the city in the 16th century, but the inscription tells us the city is way older.

My grandfather’s cousin Nelamangala Laxminarayana Rao was a chief epigraphist at the epigraphy branch of Archaeological Survey of India, but I was quite young to bother with his pioneering work.

My foray into epigraphy was unintentional. I went on to take short courses in epigraphy and pursue an MA in Kannada. I wrote a PhD thesis on the temples of the Kalyana Chalukyas based on inscriptions, and taught epigraphy for 16 years. With the support of experts, I have discovered close to 300 inscriptions and studied over a thousand in Karnataka. I am 77 now.

Stepping stone

After completing my diploma in electrical engineering, I joined the Maharashtra State Electricity Board in Amravati as a supervisor. This was in 1966. I lost my job in two years following some departmental decisions. I returned home to Nelamangala, now in the Bengaluru Rural district. To make ends meet, I started a tutorial institute for SSLC and PUC students with my brother and brother-in-law. I also ran a printing press. In my free time, I would turn to my passion for contributing features to newspapers and magazines and writing novels. I was a voracious reader and had devoured the works of Pampa, Ranna, Kumara Vyasa, Kuvempu, Da Ra Bendre, Ta Ra Subbarao, Anakru, Shamba Joshi and other literary and cultural greats from Karnataka.

Research for one of my novels took me to Mulukunte near Tumakuru, a village my mother and wife hail from. The male protagonist hails from there. ‘Parigrahana’ is a love story set against the backdrop of the ‘Down with Hindi’ movement. In the book, the couple talks about a local inscription briefly. In reality too, ‘Epigraphia Carnatica XII (Tumakuru district)’ has recorded an inscription from this place. ‘Epigraphia Carnatica’ is a set of volumes detailing the epigraphy across all the districts of Old Mysore state.

The records said that the inscription was related to the Kakatiyas from the 10th century. I challenged the claim then and I challenge it even to this day. The Kakatiya dynasty ruled between the 12th and 14th centuries. The original copperplate inscription has not been found. Villagers only had on them a paper copy of the ‘inscription’ in Sanskrit, which documented a land given to Brahmins as royal donation. The paper copy was spurious, I thought. A few epigraphists supported me but the villagers were furious as I had challenged their long-held belief. This was in the mid-1970s.

A series of serendipitous incidents followed. Kannada Sahitya Parishat started an epigraphy course and I joined the first batch with other hobbyists and history and language professors. I got a job with the Karnataka Electricity Board (KEB) in Kolar Gold Fields and was later transferred to Bengaluru. I found an inscription in Jalagaradibba around my mother’s village. It had come up during some digging work. My grandfather’s cousin studied it and published the results in The Journal of Epigraphical Society of India. It was an inscription of Sripurusha, a king of the Western Ganga dynasty, who ruled during 750 AD. Later, in the same place, I found an inscription. I believed it belonged to Madhava III of the Ganga dynasty and dated it to 390 AD. I also claimed it was older than the historic Halmidi inscription, which was dated to 450 AD. Prajavani wrote about my ‘discovery’ and senior epigraphists took note of me. But many epigraphists begged to differ. I decided to reassess my claim, and after two years, I accepted that I had erred. I redated it to 650 AD and suggested it belonged to Srivikrama, a ruler of the Western

Ganga dynasty.

I spent 8 am to 5 pm working at KEB, and the rest of my time on studying epigraphy. Epigraphy is strenuous and requires time and patience, I would realise. Perhaps why archaeology students don’t like to pursue it full-time.

Field notes

The moment I got a lead about a new inscription stone, I would show up at the site with fellow epigraphists. People on the ground, history enthusiasts, and my mentors were my informants. Often, villagers would report a case hoping it would bring them wealth.

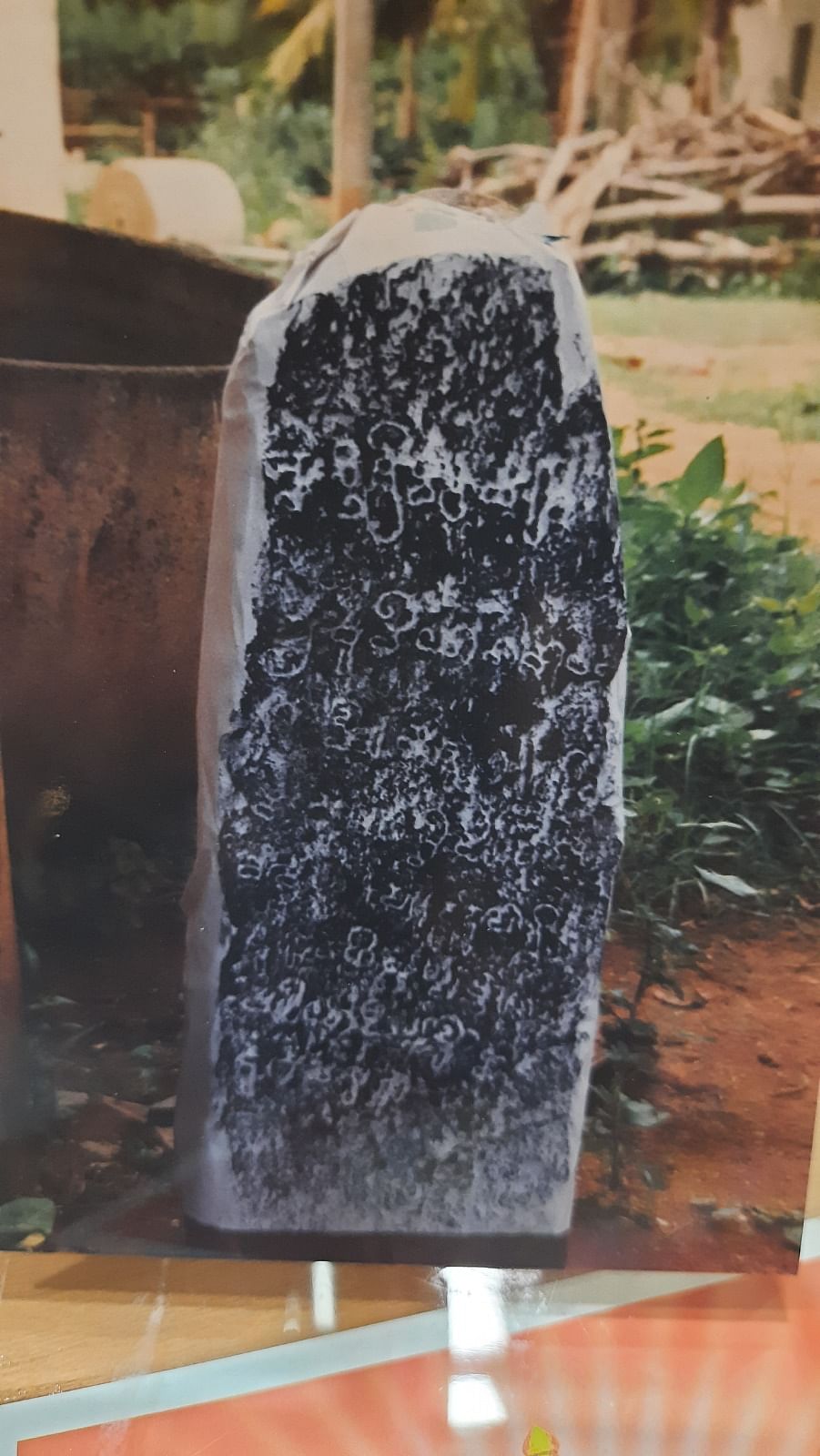

Our task was mostly two-fold — to obtain estampage, an impression of the inscribed text, and then to decipher its meaning

and date.

We would carry bundles of white papers, lamp black ink (premixed with glue the night before), a bucket to carry water, a brush, a dabber, and a camera to the site. We would wet the paper and spread it over the inscription surface. We would brush the surface to smoothen out wrinkles and then dab the ink on it gently. We had to wait until the paper dried before removing it, or it could tear. Photos of the inscription text on the bare stone before and, later, on the estampage were taken.

These expeditions were often adventures. We had to climb boulders, enter caves, get into groves, and search temple complexes. A renowned scholar, R S Panchamukhi, is said to have been lowered in a cradle with a pulley in order to take an estampage on the cliffs of Badami. A 573 AD inscription he discovered, from the time of Pulakeshin I of the Chalukya dynasty, was carved mid-boulder, 60 feet above the ground.

Landmark finding

Once I had to walk 6 km with a bucket in hand and estampage materials to reach the Sidlaphadi caves near Badami. It was while editing Kannada inscriptions of the 1st millennium when renowned historian S S Shettar suspected that an inscription of Kappe Arabhatta, a Chalukyan warrior of the 8th century, could be lingering in these caves. He requested me and Sheelakant Pattar, an English professor from Badami, to go and check it out. Sidlaphadi is a natural rock bridge, in the middle of a shrub jungle, surrounded by sandstone boulders. With no autos or taxis going there, we walked the mud path by foot. After two hours of looking around, we found the inscription of three lines.

That 750 AD Kappe Arabhatta inscription is the earliest example of the tripadi metre (three-line verse) in Kannada. It loosely means, Kappe Arabhatta was good to the good, bad to the bad, and a terror to enemies who troubled him. My assessment is that Kappe Arabhatta is none other than the great Chalukyan emperor Pulakeshin 2, who defeated Sriharsha of the Vardhana dynasty on the banks of Narmada. Many scholars differ with my conjecture.

In Karnataka, the density of inscriptions is higher in Chitradurga and Davanagere, perhaps because many wars were fought and everybody from the Kalyana Chalukyas to the Hoysalas and the Cholas ruled here.

But my field work spanned Badami, Aihole and Pattadakal in Bagalkot district, Balligavi in Shivamogga district, and Manne in Nelamangala taluk.

I mostly found inscriptions on boulders and slabs, and sometimes on copperplates. They spoke of royal grants, greatness of the kings, construction of temples, and rituals.

Hero stones (veeragallu) were sculptural works and mostly without inscriptions. They depicted stories of heroism during wars, cattle riots, and while protecting women from distress situations. The sati stones (masti kallu) were erected in memory of women who immolated themselves on the passing of their husbands.

While inscriptions praising the kings used poetic language, public announcements were straightforward.

Deciphering secrets

Taking the estampage never took much time but deciphering did because I had a day job. If I managed to crack something in eight hours, another took me over two months. As my credibility grew, I was tasked with updating existing records with new findings and didactic notes for non-Kannada readers. My greatest honour has been to revise and edit one full volume of ‘Epigraphia Carnatica’, first published by the great British epigraphist B L Rice and revised by my PhD guide and epigraphist B R Gopal. The said 25th volume contained inscriptions from six taluks of the Tumakuru district.

A grasp of languages like Kannada, Prakrit, Pali, Sanskrit and Tamil and, among scripts, Brahmi, Kannada and Tamil is essential to decode inscriptions originating in the region. A grip of local and non-regional history is critical to connect the dots. Inscriptions can inform us about Karnataka and neighbouring regions too. For instance, Krishnadevaraya, the Vijayanagara emperor, reigned over most of south India in the 16th century.

Thanks to my reading habit, I was good at old, medieval and modern Kannada and also kavyas, stylised poetry used in the royal courts. For Sanskrit verses, I would sometimes consult scholars. I am not an academic historian but I have been reading books on dynasties, cultures, archaeology and literature since the ’70s. Epigraphical works by British scholars B L Rice, J F Fleet and Walter Elliot and others go as far back as the Ashokan times (258 BC) and are a great resource. Today, my library boasts over 6,000 books.

Despite preparedness, sometimes, these relics don’t ‘speak’ the truth. Often, estampage are of poor quality because inscription surfaces are already defaced by vandals and time. Many times, inscription texts were erroneous. Three people are involved in an inscription work — a poet to compose the verse, somebody to transcribe it, and a blacksmith or a goldsmith to chisel the text. An oversight by the writer or chiseller can change the meaning.

We, epigraphists, make our fair share of mistakes. While deciphering the Jalagaradibba inscriptions, I construed a word as ‘Vikramarajya’ while my mentor B R Gopal concluded it was ‘Vikramarale’. The words have different meanings. ‘Vikramarajya’ means ‘kingdom won by power’ and ‘Vikramarale’ is the reign of Srivikrama.

Inscriptions were meant for public reading and are signs of literate cultures. And they reveal a great deal — about society, politics, economics, administration and the evolution of literature. The Gommata-stuti inscription, eulogising Bahubali, and the Badami inscription of Kappe Arabhatta are literally poems etched on stone.

As said before, with every discovery, every decipherment, we are adding new layers to history. At Manne, once the bustling capital of the Ganga dynasty, I came across a copperplate inscription that was published in ‘Epigraphia Carnatica IX’. It spoke of one officer Srivijaya who had built a Jain basadi (shrine) here. My hypothesis is that he is the same Srivijaya who is believed to have authored ‘Kavirajamarga’, during the reign of Rashtrakuta king Amoghavarsha I. ‘Kavirajamarga’ is the earliest available Kannada work on poetics.

Update textbooks

Life has come full circle. I am back to writing novels, where my epigraphy journey started. I don’t go on expeditions because age is not on my side. But I decipher, study and edit inscriptions when such opportunities are presented to me.

I still wish to research the people’s history of Karnataka through the lens of inscriptions — not of the kings. I am still concerned about the disregard towards old sites on the part of archaeology departments, local residents, and real estate builders. On one visit to Manne, I saw a villager using an ancient stone, bearing an inscription of a Jain lady, as a footpath slab. Locals have also stolen bricks from the temple site there.

I think the efforts of historians, archaeologists and allied experts are futile if we don’t revise history lessons in school textbooks with the latest research findings. Why should political ideologies guide our textbooks?

Epigraphy goes digital

Bengaluru may be on the cusp of disrupting the conventional approach to epigraphy.

Inscription Stones of Bengaluru, a citizen initiative, and Mythic Society, a 114-year old NGO focused on Indic studies, are recording inscriptions using advanced handheld scanners and creating 3D models.

This is in contrast to making estampage and reading scripts manually, a process that hasn’t changed since the 1800s, says P L Udaya Kumar, honorary director, 3D Digital Conservation Project.

The digital intervention was needed because “most senior epigraphists are too old to go on field explorations and we stand to lose their expertise.”

Since 2021, they have scanned 600 inscription stones across Bengaluru Urban, Bengaluru Rural, and Ramanagara districts. “We now have a database of 30,000 Kannada characters, spanning 6th to 16th century. This comprises unique characters but also variations prompted by handwriting and chiselling styles. We plan to make the database open-source (in a bid to engage citizens),” says Udaya.

He rues citizens like him have long been filling in responsibilities that should have been pioneered by the state. “Epigraphy is a rarefied career. The Karnataka archeology department doesn’t have a single epigraphist. Nobody applies, they say,” he claims.

This is unfortunate because inscriptions are regarded as the most reliable source of history. “Since they are carved in stone and displayed in public, you can’t manipulate the text,” he explains.

Epigraphy courses

Kannada Sahitya Parishat and Karnataka Itihasa Academy in Bengaluru, and Kannada University in Hampi, offer courses that range from one to three years.