Politicians are not famed for saying anything original or entirely honest. However, there are two speeches which remain some of the finest words spoken in a nation’s history.

'Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.’ So begins Abraham Lincoln’s great address on the battlefield in Gettysburg in the midst of the American Civil War. The other speech was made by India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Nehru, moments before India became independent: 'Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem that pledge… On the stroke of the midnight hour when the world sleeps India will awake to life and freedom.'

Unforgettable words, almost Biblical in their simplicity and power, embracing the nations’ past, as well as cradling a vision for their future.

I was 10 when India became independent. Just old enough to rejoice since everyone did. And because our father believed we should share this great experience, we watched the British flag come down at midnight and saw the tricolour flutter in its place. Memory is vague and disjointed, but I can remember the joyousness everywhere, the sense of being in a new world. Patriotism was a part of this world, of our lives. It did not have to be enforced, it was in the very air around us; we inhaled it with every breath. Nor did patriotism stand alone; it was clubbed with sacrifice, with non-violence, austerity and the truth. And with 'wiping every tear from every eye.'

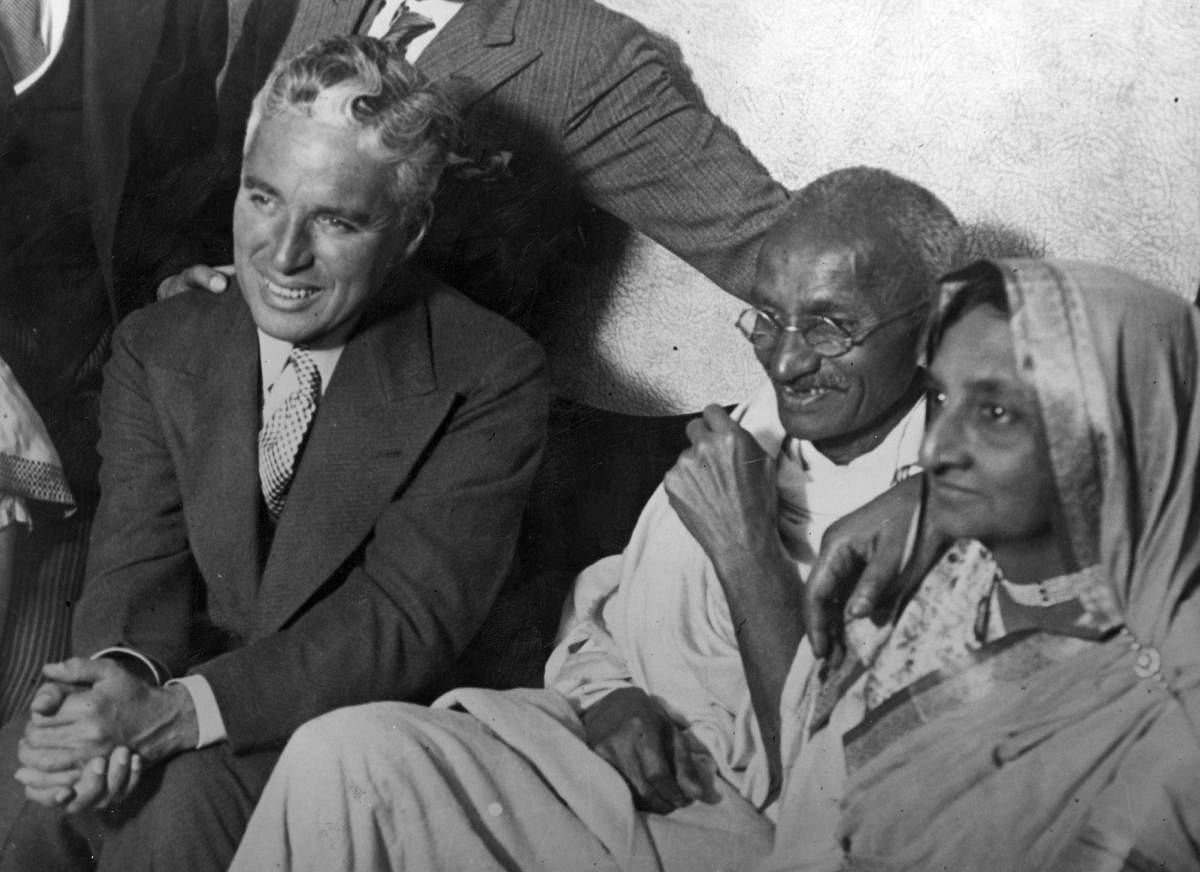

It was with these weapons that Gandhiji and his followers scripted a unique story of a non-violent struggle for freedom. Some magic in the man and his beliefs drew a great many people into the movement. I heard that when Gandhiji came to our town Dharwad and asked people to donate to the freedom movement, women gladly gave their gold bangles, perhaps the only little bit of gold they had. It was a lived idealism, not a theoretical one.

Then came the terrible times. Partition riots, killings, rapes, huge masses of homeless refugees, Kashmir, Hyderabad — all these and more had to be confronted. Above all, there was the assassination of Gandhi. What would we do without him? The doomsayers said Indians would never be able to govern themselves. But we did. We got ourselves a Constitution (a difficult task for such a large and complex country), we held elections, and institutions and systems were put in place. But it was soon clear that something was wrong.

My father, the dramatist Shriranga, wrote a play, Shokachakra, after Gandhiji’s death. It was about a committed Gandhian who had led his town during the freedom struggle. But once freedom came and men smelt power, they got rid of the man who had become a liability with his insistence on Gandhian principles. To watch the tragedy of this man was like seeing the death of Gandhi all over again. There was pin drop silence when the curtain fell.

A writer myself, I wonder now at the dramatist’s prescience. 'Just for a handful of silver, he left us/ Just for a riband to stick in his coat." Lines from Robert Browning’s The Lost Leader, lamenting a leader who reneged on his liberal idealism, accepting a pension and the position of Poet Laureate from the government.

The renegade poet was Wordsworth. One turncoat. How many turncoats do we have among us now, men who, for that handful of silver, are willing to do anything? Multitudes, who turn their backs on the people who voted for them, multitudes who no longer hear the voices of the people they represent. Worse, there is no sense of wrongdoing in them. And Gandhi has become only a sketch of an old man with a stick, a man whose name we may remember, but whose teachings we have forgotten. It is but right that each age should have its own dreams, its ideals. But when I think of what our earlier ideals have been replaced with, I come up with a blank.

Ursula le Guin, an American writer, in an essay titled Freedom wrote: 'Hard times are coming when we’ll be wanting the voice of the writer. We will need writers who can remember freedom.' And added, 'We who live by writing and publishing want and should demand our share of the proceeds; but the name of the beautiful reward isn’t profit. The name is freedom.’

Through the ages, women and men, writers and others have fought for this beautiful reward of freedom. It is a fight that will never cease.

(The author is a well-known novelist.)