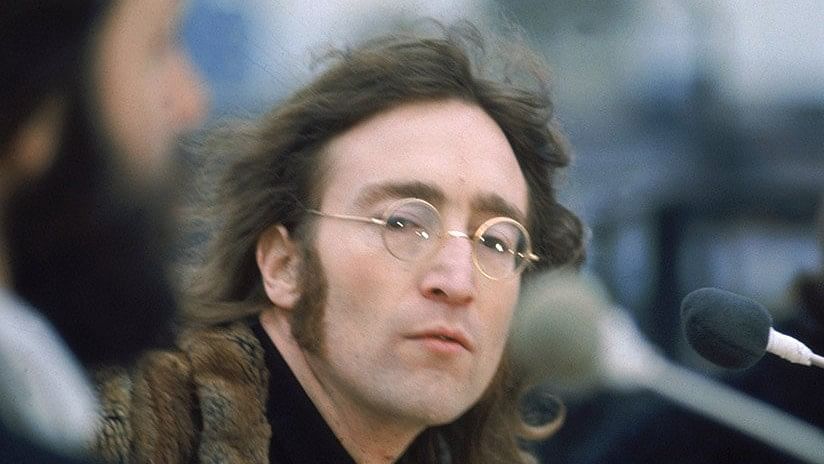

John Lennon of The Beatles

Credit: X/@thebeatles

By Steve Vincent for The Conversation

Queensland: When you think of John Lennon from The Beatles, you’re likely to picture him with his circular, wire-rimmed glasses.

But at times, he wore contact lenses, or at least he tried to. They kept pinging out of his eyes.

Why and what Lennon did to help his contacts stick is part history and part vision science.

As I propose in my paper, it also involved smoking a lot of pot.

Lennon didn’t like wearing glasses

Before 1967, Lennon was rarely seen in public wearing glasses. His reluctance to wear them started in childhood when he was found to be shortsighted at about the age of seven.

Nigel Walley was Lennon’s childhood friend and manager of The Quarrymen, the forerunner to The Beatles. Walley told the BBC,"He was as blind as a bat – he had glasses but he would never wear them. He was very vain about that."

In 1980, Lennon told Rolling Stone magazine,"I spent the whole of my childhood with […] me glasses off because glasses were sissy."

Even during extensive touring during Beatlemania (1963–66), Lennon never wore glasses during live performances, unlike his hero Buddy Holly.

Then Lennon tried contacts … ping!

Roy Orbison’s guitarist Bobby Goldsboro introduced Lennon to contact lenses in 1963.

But Lennon’s foray into contact lenses was relatively short-lived. They kept on falling out – including while filming a comedy sketch, on stage (when a fan threw a jelly baby on stage that hit him in the eye) and in the pool.

Why? That’s likely a combination of the lenses available at the time and the shape of Lennon’s eye.

The soft, flexible contact lenses worn by millions today were not commercially available until 1971. In the 60s, there were only inflexible (rigid) contact lenses, of which there were two types.

Large “scleral” lenses rested on the white of the eye (the sclera). These were partially covered by the eyelids and were rarely dislodged.

But smaller “corneal” lenses rested on the front surface of the cornea (the outermost clear layer of the eye). These were the type more likely to dislodge and the ones Lennon likely wore.

Why did Lennon’s contact lenses regularly fall out? Based on the prescription for glasses he wore in 1971, Lennon was not only shortsighted, but had a moderate amount of astigmatism.

Astigmatism is an imperfection in the curvature of the cornea, in Lennon’s case like the curve of a rugby ball lying on its side. And it was Lennon’s astigmatism that most likely led to his frequent loss of contact lenses.

At the time, manufacturers did not typically modify the shape of the back surface of a contact lens to accommodate the shape of a cornea with astigmatism.

So when a standard rigid lens is fitted to a cornea like Lennon’s, the lens is unstable and slides down when someone raises their upper eyelid. That’s when it can ping from the eye.

What’s pot got to do with it?

Lennon realised he could do one thing to keep his contact lenses in. According to an interview with his optometrist, Lennon said,"I tried to wear them, but the only way I could keep them in my bloody eyes was to get bloody stoned first."

So how could smoking pot help with his contact lenses?

This likely led his upper eyelids to droop (known as ptosis). We don’t know how exactly cannabis is related to the position of the eyelid. But several animal experiments have reported cannabis-related ptosis. Cannabis may reduce the function of the levator palpebrae superioris, the muscle that raises the upper eyelid.

So while Lennon was stoned, his lowered eyelids would have helped secure the top of the lens in place.

Lennon wore contact lenses from late 1963 to late 1966. This coincides with The Beatles’ peak use of cannabis. For instance, Lennon refers to their 1965 Rubber Soul album as “the pot album”.

Back to glasses

Ultimately, Lennon’s poorly fitting contact lenses led him to abandon wearing them by 1967 and he began wearing glasses in public.

His frustrating experience with contact lenses may have played a role in the genesis of his iconic bespectacled look, which is still instantly recognisable over half a century later.

(Steve Vincent is Professor of Optometry and Vision Science, Queensland University of Technology)