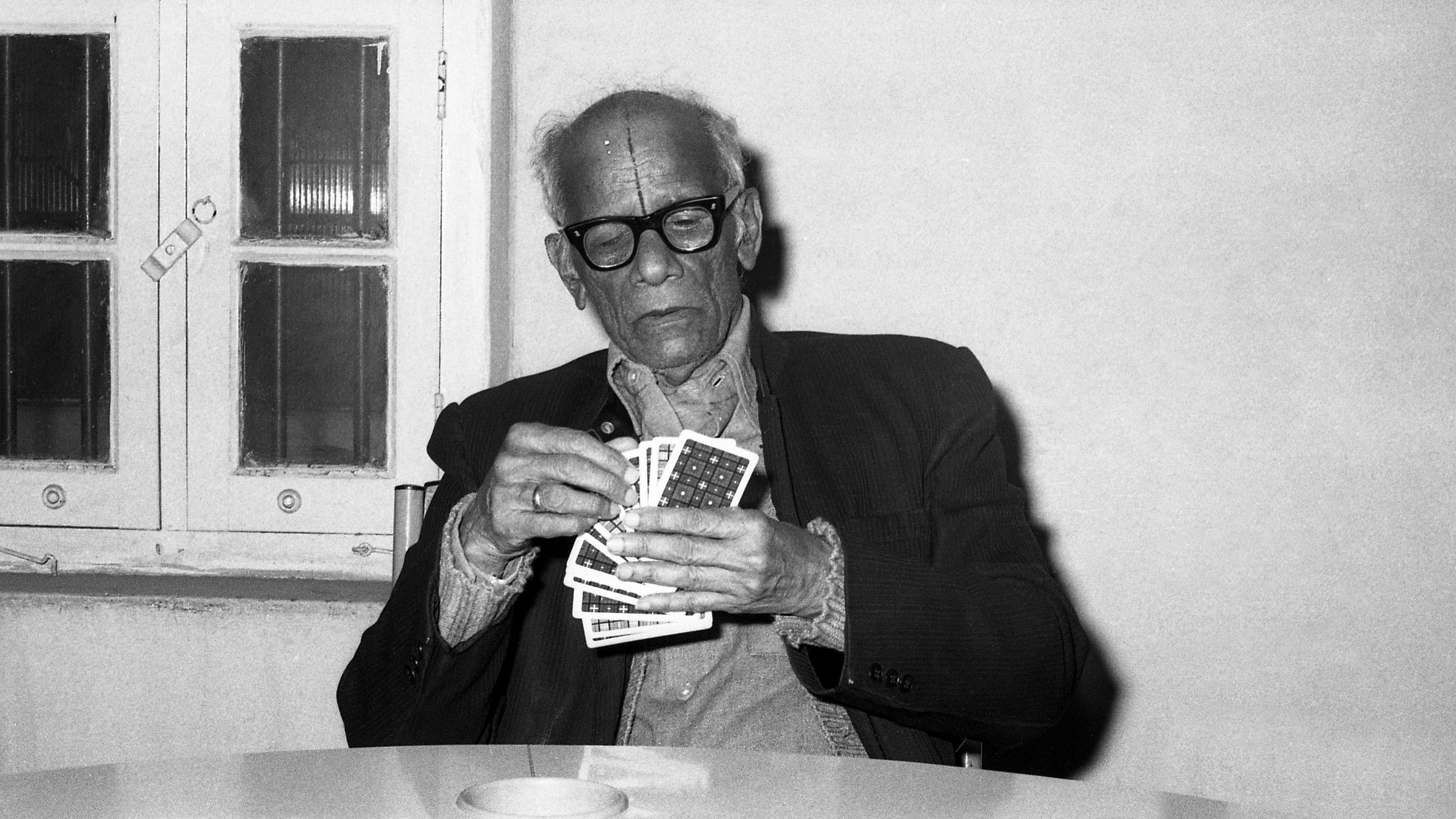

Masti Venkatesha Iyengar, (1891-1986), the towering Kannada writer popularly known as ‘Masti’, has left a prodigious body of work spanning short stories, novels, plays, poetry, philosophical meditations, essays, biographies and an autobiography in four volumes, an admirable chronicle of his times that captures the full and rich life he lived.

But he is most renowned for his masterly short stories and is regarded as the father of Kannada short stories.

Kannada literary works can be traced back more than a thousand years and their grandeur lay in poetic forms of epics influenced by Sanskrit that were monumental in scale. Other literary forms — grammar, prosody, the incomparable vachanas, devotional literature, etc., also flowered in splendorous varieties. However, the genre of modern short stories and the modern novel, termed Navodaya Sahitya, which evolved into a fine literary form in European languages, especially English, French and Russian by the early 18th century, found its full expression in Kannada only a hundred years later.

Impish and earthy

The first modern Kannada short story Rangana Maduve (Ranga’s Marriage), a delightful tale sparkling with impish humour and earthy style that captures the emotions of budding love, bracing like the first monsoon breeze of the season, was published by Masti in 1910. Following this, a steady stream of 300 stories, like a perennial mountain spring, gushed out from the fount of his heart and his luminous mind for the next 75 years. His last story Maatugara Ramanna (Talkative Ramanna) saw print in 1985 a year before he died in 1986.

In these 300 stories, he dived into the very depths of the human soul and illumined every facet of human character and behaviour — conjugal life, lust, coveting a neighbour’s wife, cohabiting outside marriage, adultery, incest, deceit and the hypocrisies of saints and godmen.

He stands alongside the same pantheon as the two other incomparable short story writers — the French fiction writer Guy de Maupassant and the British novelist William Somerset Maugham, whose influence is visible in Masti’s stories. Masti, a gold medallist in English literature from Madras University, had a scholarly knowledge of that language, was well-read in Sanskrit and Tamil, and had an oceanic sweep and grasp of ancient Kannada literature.

Accident of birth

In a very deeply touching story, Beediyalli Hoguva Naari (The Lady Walking On A Street), Masti delicately crafts a fine story that anchors around a prostitute. Srinivasaiah, a well-to-do landlord, gets invited to the house of a very attractive lady, Nagaseni. Unaware she is a courtesan, while boarding a train, he happens to rescue her from some ruffians hovering around her. As he eases into a conversation with her when he visits her well-appointed house, he cannot escape her self-possession and dignified demeanour. Observing her makeup and body language, a few doubts creep into his naive mind.

She is cultured, considerate and generous in her disposition. She offers her services and the hospitality of her place in reciprocation and as a token of gratitude for his help and for showing concern for her at the train station. Srinivasaiah politely declines even as he looks at her keenly. Thinking he rejected her because of her age, she offers the services of her daughter. He recoils, and says, it was not her age and he did not come seeking pleasure. Then, when he is about to take leave, she requests him to wait and goes inside and comes back holding a photograph of a man with aristocratic looks. The lady tells him the man in the photograph was her patron and fondly remembers him, saying he always respected her. Srinivasaiah is taken aback. It is his father. She says, “He took care of my mother. Please allow me to serve you and take care of you.” She then falls at his feet. Srinivasaiah raises her gently, plants a kiss on her forehead and reveals to Nagaseni that she is his sister. He thanks her and bids goodbye, leaving her in tears and a state of shock.

As he walks out of the house, he sees peeping out of the window the stunningly beautiful daughter of Nagaseni, enchanting like the full moon. And his daughter Kamalu’s face flits past his inner eye. His mind is in a tumult, stunned by the revelation. He reflects on the high ethics and gratitude of the lady who wanted to repay an act of goodwill. How an accident of birth is like a dice rolled by the creator and can be so unjust. She also serves the needs of a section of society just as a doctor, engineer or teacher. The same society casts aspersions on her and is judgemental. She is a mother, a daughter and a sister if she is born in your house. But if fate decreed otherwise and she is born in a brothel to your father, she becomes a prostitute. A prostitute is his sister. She shares his blood. He could have been born in that house. How is Srinivasaiah any superior? As these thoughts consume him in the darkness, Srinivasaiah reaches his home.

Maugham & Maupassant

This reminds us of Maupassant’s greatest short story ‘Boule de Suif’. In that extraordinary story, Maupassant narrates the events during the Franco-Prussian war when a group of 10 travellers in a small French village board a horse carriage at midnight to escape from the German occupation army. Among them are a plump prostitute Elisabeth, a politician, a bourgeois merchant couple, a wealthy factory owner and his wife, a nobleman and his spouse, and two nuns. They represent a microcosm of French society. Along the way, Elisabeth shares her delicious meats lovingly with her fellow hungry passengers. After long hours of travel, they take lodgings for the night on a wayside inn and realise to their horror that it is under the command of a Prussian officer and become his captives. The officer takes a fancy to Elisabeth and wants to sleep with her. She firmly refuses on the principle of resisting an invader. A couple of days pass. The officer conveys they can travel further only after Elisabeth obliges him. Elisabeth refuses to be conquered by the enemy. Her fellow travellers urge her with cruel comments to make the sacrifice for the rest as it is her job to sleep with men. The pious nuns say they have to rush to the war front to look after the injured soldiers and justify her sleeping with the officer on moral grounds. She finally gives in. Maupassant paints Elisabeth as a fierce and courageous patriot whose resistance grows throughout the story and portrays her as morally admirable, juxtaposing her against the sanctimonious hypocrisy, selfishness, pettiness, craftiness and snobbishness of the other travellers.

In the famous story ‘Rain’ by Somerset Maugham, a ship sailing to Apia, a tiny island in the South Sea Islands, anchors at Pago Pago. There is an outbreak of an epidemic and the ship cannot sail until it is sure no one on board the ship is infected. An American doctor and his wife and a missionary Davidson, who are passengers on the ship, take lodgings on the waterfront. A ‘hooker’, Miss Thomson, from the ship, also takes room there. It rains heavily all day and night. Through the sound of the rain, they hear loud music and laughter and voices of men shuffling around her room.

The missionary, who constantly boasts of his charity work with the doctor — to uplift the lives of tribals which he finds to be immoral — is determined to stop Miss Thomson’s “vile” activities. He meets her often, prays for her and tries to change her into a “better” person. He gets familiar with her. He tells the doctor triumphantly: ‘‘It’s a true rebirth. Her soul, which was black, is now pure and white. All day I pray with her...’’ Two days later, Davidson is found dead on the beach. He had cut his throat with a razor. Miss Thomson’s room is abuzz again with music and men. The Doctor understands everything when she says to him jeeringly, “You men! You filthy dirty pigs! You’re all the same, all of you.”

Not preachy

In the story Venkatigana Hendathi (Venkatiga’s Wife) Masti captures evocatively the searing tale of intense love and forgiveness of a young labourer Venkatiga and his wife who both make a living in a village near Tirupati. A rich upper caste landlord’s eyes fall upon her and he seduces her with expensive gifts. She leaves her husband and moves to the already-married landlord’s house as his mistress. Deeply distressed, Venkatiga leaves his village and moves to a hamlet close to Bengaluru and finds work cutting and selling firewood.

The rich man brings another mistress to the house after about a year. Deceived and distraught but determined, she leaves him. On learning that her husband had left the village, she goes in search of him. One day, she arrives at his hut with a child in her arms. She sees him, goes down and touches her forehead to the ground, places the child on his feet and cries, “Keep me or kill me.” Venkatiga raises her gently, takes the child in his arms and leads her inside.

After a few hours, she points to the child and says, “Look at its nose. It is like yours!” Why should he scrutinise? How does it matter whose child it is? It is God’s gift — Bala Gopala. He says “Yes” — happy that his affirmation gives her comfort.

Masti, like all great novelists, portrays through the story, the lofty character and the nobility of the poor and oppressed while contrasting it with the smug, rich and educated middle class, without ever being didactic and preachy.

Masti’s stories offer a kaleidoscopic view of life. He is empathetic and humane. He doesn’t judge. His writings are an attempt to understand life and its unending mysteries.

(The author is a soldier, farmer and entrepreneur.)