At a time when technology is spawning smart solutions to combat Covid-19 worldwide, India’s digital response to the pandemic has stoked concerns that surveillance could pose threats to the privacy of the personal data collected. Be it apps or drones, there is widespread criticism that digital tools are being misused to share information without knowledge or consent. At the other end of the spectrum, the great urban-rural digital divide is hampering the already sluggish vaccination drive, exposing vulnerable populations to a fast-mutating virus.

Last year, the Centre, states and municipal corporations launched more than 70 apps relating to Covid-19, demonstrating the country’s digital-driven approach to handling the pandemic. Chief among these was the central government’s contact tracing app Aarogya Setu. Launched under the Digital India programme, the app quickly came under scrutiny over data privacy.

As per its privacy policy, Aarogya Setu collects personal details such as name, age, sex, profession and location. As there is no underlying legislation forming its basis, and in the absence of a personal data protection bill, serious privacy concerns regarding the collection, storage and use of personal data have been raised.

The government has attempted to mitigate these concerns with reassurances that the data will be used solely in tracing the spread of the virus. However, recent reports from the Kulgam district of Jammu and Kashmir point to the sharing of application data with police. This demonstrates how easy it is to use personal data for purposes other than which it was collected, and presents a serious threat to citizen privacy.

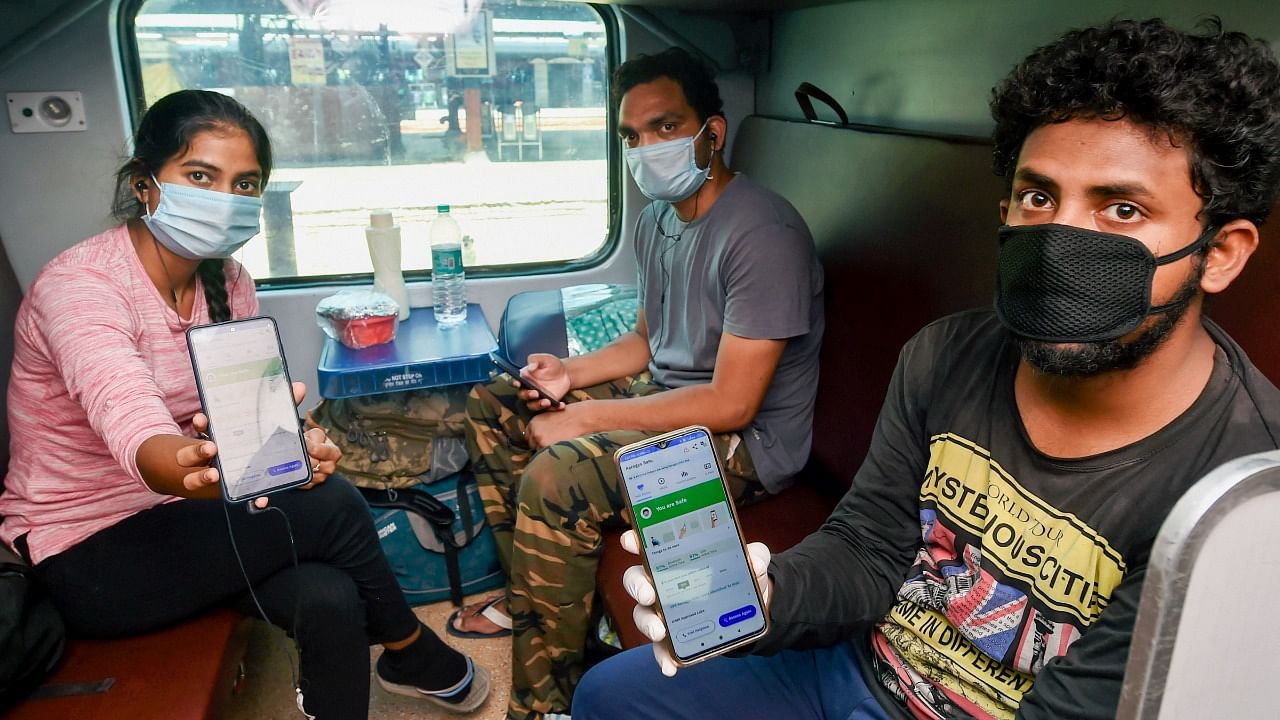

Though Aarogya Setu was initially launched as ‘consensual’ and ‘voluntary’, it soon became mandatory for individuals to download the app for various purposes such as air and rail travel (this order was subsequently withdrawn) and for government officials. Initially it was also mandatory for the private sector, but this was later watered down to state that employers should, on a ‘best effort basis’, ensure that the app is downloaded by all employees having compatible phones. However, the ‘best effort basis’ soon translated into mandatory imposition for certain individuals, especially those working in the ‘gig economy’.

Several states had also launched apps for various purposes ranging from contact tracing of suspected Covid patients to monitoring the movement of quarantined patients. As a report by the Centre for Internet and Society observed, given the attention on Aarogya Setu, most of the apps launched by the state governments escaped scrutiny and public attention.

Most of these apps either did not have a privacy policy or the policy was vague and often did not provide important details such as who was collecting the data, the time period for retaining the data and whether personal data could be shared with other departments, most notably, law enforcement.

Apart from contact tracing apps, the pandemic also ushered in a wave of other apps and digital tools by the government. These include systems such as drones to check whether people are following Covid-19 norms and facial recognition cameras to report to the police whether someone has broken quarantine. Similar to Aarogya Setu, these tools have also largely been brought about in the absence of a legal and regulatory framework.

The absence of any legal framework has meant these tools are now being used for purposes beyond managing the pandemic.

The government is now planning to use facial recognition technology along with Aadhaar to authenticate people before giving them vaccine shots.

Aarogya Setu is now linked with the vaccination process. Beneficiaries have been provided an option to register through Aarogya Setu. The pandemic has also provided a means for the government to bring in changes to health policies and introduce the National Health Data Management Policy for the creation of a Unique Health Identity Number for citizens.

Vaccination and digital platforms

The use of digital technology has extended to the vaccination process through the deployment of the Covid Vaccine Intelligence Network (Co-WIN) platform.

During the first phase of inoculation, beneficiaries were required to register on the Co-WIN app while in the subsequent phases, registration was to be done on the Co-WIN website. The beneficiary is required to upload a photo identity proof.

While Aadhaar has been identified as one of the seven documents that can be uploaded for this, the Health Ministry has clarified that Aadhaar is not mandatory for registration either through Co-WIN or through Aarogya Setu. However, as per media reports, certain vaccination centres still seem to insist on Aadhaar identity even though beneficiaries may have used another identity proof to register on the Co-WIN website.

It is also pertinent to note that the website did not have a privacy policy till the Delhi High Court issued directions on June 2, 2021. The privacy policy hyperlinked on the Co-WIN app directed the user to the Health Data Policy of the National Health Data Management Policy, 2020.

The vaccination drive has been used as a means to push the health identity project forward as beneficiaries who have opted to provide Aadhaar identity proof have also been provided with a health identity number on their vaccination certificate. It is interesting to note that Co-WIN’s privacy policy now states that if the beneficiary uses Aadhaar as identity proof, it can ‘opt’ to get a Unique Health Id. However, as a recent report revealed, health identity numbers have already been generated for certain beneficiaries without obtaining consent from them for the purpose.

Have the apps been successful?

One could argue that privacy concerns are a worthwhile tradeoff in order to contain the spread of the pandemic. But it is worth examining how successful these technologies have been. In reality, the use of digital technology at every stage of combating the pandemic has clearly highlighted the extent of our digital divide. As per data from TRAI, there are around 750 million Internet subscribers in India, which is only a little more than half of India’s estimated 1.3 billion citizens — with this gap having a significant impact on the efficacy of the government’s strategies.

Aarogya Setu has fallen far short of its goal, of having near universal adoption. It has limited adoption in much of the country. This has severely limited its efficacy in tracing the spread of the virus. Research from Maulana Azad Medical College has cited socio-economic inequalities, educational barriers and the lack of smartphone penetration as being the key causes behind the app’s limited success, pointing back to the digital divide. Moreover, the app has also brought with it a host of associated problems including lateral surveillance and function creep caused by the addition of new features. All of which, along with the previously mentioned privacy concerns, have served to hamper public trust and adoption.

A similar situation is seen in the case of vaccination and the Centre’s Co-WIN web portal. The need for registration, first on the Co-WIN app and later on the Co-WIN web portal, has disproportionately affected those who either have no or limited digital access. Many of them belong to vulnerable groups such as migrant and informal sector workers (mainly from disadvantaged castes), LGBTQIA+ individuals, sex workers and both urban and rural poor. These issues have also been acknowledged by the Supreme Court, which raised serious concerns about the government being able to achieve its stated object of universal vaccination.

As the inoculation exercise opened up for the 18-45 age group, it increasingly favoured the urban population who possessed the technological and digital literacy to either create or access a host of tools. One need to only look at the wave of automated Co-WIN bots that arose as soon as the vaccination process was expanded to see how these dynamics manifested.

Ultimately, the digital-driven approach that the governments have adopted has resulted in a number of issues — most notably, data privacy and exclusion. Going forward, government strategies must actively account for these factors and ensure that citizen rights are adequately protected.

(Aman Nair is a Policy Officer at the Centre for Internet and Society, Pallavi Bedi is a Senior Policy Officer at the Centre for Internet and Society)