Almost lost in the expansive archives of the Tuebingen University Library in Germany, a nugget of history and culture of Tulu Nadu was rediscovered by professor B A Viveka Rai in 1989. Mistakenly filed along with Malayalam manuscripts, written in Kannada script, this Tulu text contained a few paddana songs, as documented in the 1850s by Hermann Moegling, the editor of the first Kannada newspaper ‘Mangalura Samachara’.

Fifteen years later, when ‘The Siri Epic’, a major Tulu folk anthology comprising the original text and English transliteration of the paddana of Siri daiva — a deity of Tulu Nadu — was published, it gathered the attention of folklore enthusiasts and researchers around the world. The anthology was documented as sung by Gopala Naika, a paddana singer from Machar village near Ujire in Belthangady taluk of Dakshina Kannada, who recollected the epic from memory like other singers. The work brought this form of folklore and the artiste to the fore.

Documentation efforts

In terms of volume, the anthology was almost equivalent to Homer’s Greek epic Iliad and it soon received acclaim because such documentation efforts were few and far between.

The paddanas are important epics in Tulu language. These songs narrate the origin, and adventures of ‘Jarandaya’, ‘Panjurli’ and ‘Kallurti’ and other deities of Tulu Nadu and propagate social ideals. Paddanas are also dedicated to the cultural heroes of Tulu Nadu like Koti and Chennayya. In Siri paddana for example, there is an emphasis on women’s identity and in Koti-Chennaya paddana, we see the significance of equality.

The songs are mainly sung on the occasion of the famed Tulu Nadu traditions of daivaradhane or bhootaradhane (demi-god worship). The singing of the paddana songs, comprising myths and stories is a living tradition as they are centered around the artist and are subject to regional variations. Artistes have the liberty and the ability to construct and reconstruct paddana around the storyline. This makes each paddana special.

Explaining what makes these folk songs dynamic in nature, Rai says, “There are a number of variants to each of them. For example, there are more than five versions of the Panjurli epic.” Folk researchers emphasise that the inclusion of several versions and the recognition of their validity is one of the special features of folklore in every part of the world.

These days, the folk performers may have other professions. However, they are from the oppressed classes and hence paddana also acts as a medium through which they reflect their agony through the songs.

On several occasions, the daiva performance is given more importance than the singing padanna. However, the paddana has an equal relevance as its main function is to mentally prepare the performer for his role, making them inseparable.

“The paddana not contains details on what the rituals, make-up and ornamentations of the particular daiva during the daivaradhane should be. Hence it is an explanation of the ritual performance as well,” Dr K Chinnappa Gowda, folklore scholar and former Vice Chancellor of Folklore University, Haveri. Normally, excerpts of a paddana are sung during daivaradhane as well.

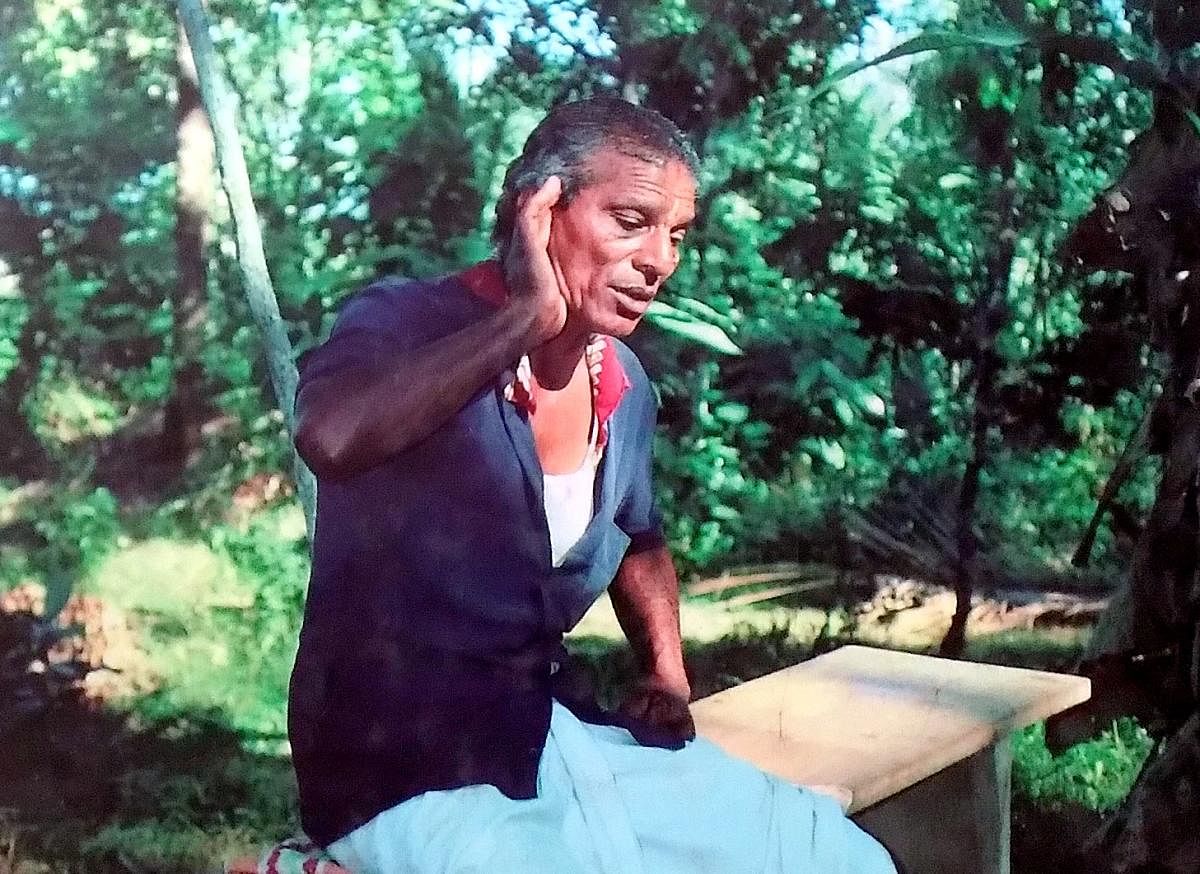

Since the epic relies so heavily on singers to pass down through the generations, daiva artistes are the true owners of the tradition, Gowda explains. “The daiva performer is expected to be acquainted with the paddana which is nothing but the history of the daiva he is representing. However, during the performance, he will not be able to sing along and therefore, another artiste, most probably his wife or mother will accompany him by singing the paddana, along with playing a ‘dudi’ (a small, handheld percussion instrument),” he adds.

Ananda Nalike from Aduru, Kasargod, says that his family has been in the profession of daivaradhane for generations. “The paddana songs were handed down to me by my father. Now, my children are observing the rituals and learning paddanas,” he adds.

“Paddana singers orally interpret the story of a daiva, recollecting the entire story from their memory,” says Viveka Rai, folklore scholar and former Vice Chancellor of Kannada University, Hampi.

These songs are mostly confined to ‘Kola’ and ‘Nema’, forms of daivaradhane in Tulu Nadu.

In the early 70s, several Yakshagana plays were based on paddana, including ‘Koti-Chennaya’, ‘Karnikada Kordabbu’ and ‘Satyanapurata Siri’. Yakshagana artistes like Mijar Annappa, Alake Rama Rai, Christian Babu and Malpe Ramadasa Samaga popularised these plays. However, paddana-based Yakshagana plays are less common today.

Diminishing culture

Other occasions during which the paddanas are sung include paddy transplantation and harvest. These forms of paddanas are called ‘kabitha’ songs. Kabitha songs consist of short lines and are generally written in praise of deities. They talk about the significance of agricultural activities. When a female worker starts singing the kabitha, the others repeat and sing along. ‘O bele’ and ‘O Manjotti Gona’ are some of the popular paddy folk songs.

Today, the tradition is diminishing, as there are few people who sing these songs. As it is largely an oral tradition, the disappearing singers mean that 40% of paadana texts have been lost, explains former Chairman of Karnataka Tulu Sahitya Academy, Dayananda Kattalsar.

“The paddana culture is diminishing due to fragmentation of agricultural lands. These lands end up being used for commercial purposes over a period of time,” says a person who is in service of a daiva. Coupled with mechanisation in the field, singing paddana in fields has become more of a rare occurrence over the years, he says.

Noting that there may be around 200 to 300 paddana artists in Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts, Kattalsar highlights the need for documentation. “The government must set up a separate study centre for the documentation of Tulu folklore,” says Kattalsar. He added that the documentation should be supervised by those who are directly involved in the field of daivaradhane.

Along with the documentation of paddana, documenting the dialogue with the singer is also important, Rai says. “Telling the oral epic through a digital platform is the need of the hour,” he says. This could serve as an effective method to aid the learning of the oral tradition as well.

(‘The Siri Epic’ was the fruit of the work of Lauri Honko, Anneli Honko, K Chinnappa Gowda and B A Viveka Rai)