Every city has a significance that becomes evident as soon as one enters it. Firozabad in Uttar Pradesh is no exception. The moment I enter it, I know I am in the city of bangles. I can see long garlands of red, green, yellow, orange, blue, black, white and pink bangles being ferried on cartwheels and motorbikes. It looks like a rainbow of glass bangles everywhere.

Bollywood has romanticised bangles since its earliest days — Achoot Kanya(1937) features the song Chudi main laya anmol re. My friends living in China tell me Mere hathon mein nau nau chudiyan(1989) and Bole chudiyan bole kangana ( 2001) are the most popular songs there. Ekta Kapoor’s TV serials have also made bangles a fashion statement.

My ‘hero’ for the Firozabad trip is 52-year-old Azhar Nafees, a family friend. His extended family owns Firozabad’s largest bangle factories. Azhar bhai, as I call him, has been long unwell. He underwent a kidney transplant a year ago. He becomes breathless and sweats excessively. But he is so passionate about bangle making that in the hot month of June, he takes me around the city on his motorbike while his longtime associate Guddu bhai follows on a scooter.

Azhar’s family gives me VIP treatment. The women usually wear burqas and don’t allow the media to take pictures, but his wife and an elderly woman wear bangles and obligingly pose for my camera.

Also Read | Labour pains

Azhar’s factory, Patel Glass House, stands on a sprawling 15 acres, but has remained shut for a couple of years. Slump in the market, he tells me. So he takes me to his paternal uncle Anwar’s factory, and also to small units on the streets of Shitai Khan Road, where bangles are designed, polished and packed into boxes.

Work in progress

I enter his cousin’s 40,000 sq ft factory, Mahavir Glass House. We walk along a corridor with huge heaps of mud, sand, mica and broken bangles on one side and water pits for industrial use on the other.

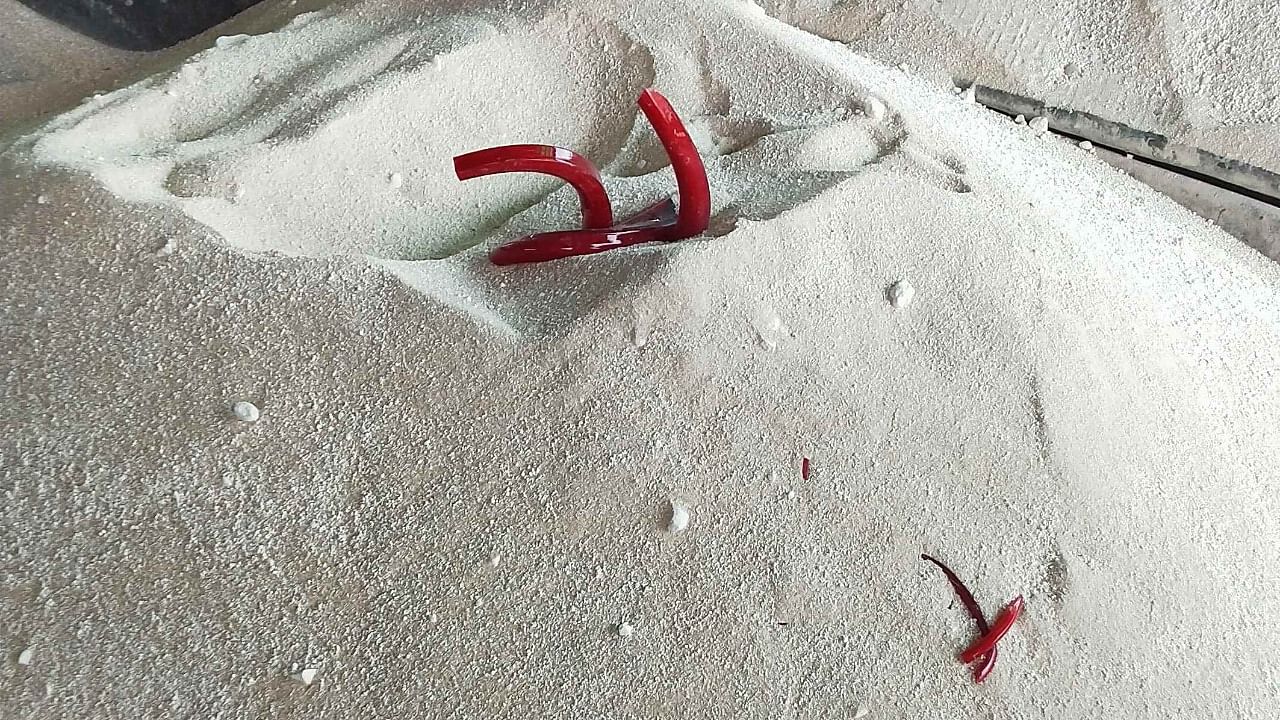

A 50-metre walk leads me to an expansive space. It feels like I have come out of a tunnel to see a bright new world of glass. It is stunning. Red bangles are strewn everywhere. I have to walk carefully. If I step on a red hot mould, I risk burning my feet and also damaging the product.

Contrary to reports that children are hired for work, I see labourers between 25 and 60 years of age sitting in groups of three to five. With a diamond cutter in hand, they are separating the bangles from a fiery hot mound of glass. Showing the cutter to me, Azhar says, “The edge is so sharp that newcomers often cut their fingers. It takes a month or two to learn how to separate the bangles with the cutter.”

“So, you mean, I can’t make a bangle here for my story?” I ask. The workers burst out laughing. “No way. Unless you give us two months to teach you, we won’t even let you touch anything,” he says.

A bangle undergoes 28 processes before we finally wear it (see box) and I had set aside only two days for this visit! The work titles for these processes go by the names judai, katrai, sadhai, rangai, urayi, pirayi, baghari, etc.

My protective mentors keep me at arm’s length from the furnace. I won’t be able to bear the heat if I go closer, they warn. Sometimes, I am in their way as they shift hot coils to the open area. As I hear heavy screams of hato, hato (move away), a worker runs in with a long pole of molten glass and twirls it in a machine. My guides save me from the pole hitting my head.

I am terrified of getting burnt. I still ask if I can try rotating a pole with the molten glass on it. Guddu says, “Madam, this needs experience and training. It is done in seconds and it is too heavy to hold.” I give up.

Ghee insurance

The workers smile for my camera. One shows his dark, burnt hands. Another has lost half his index finger while working. Some have burns on the face and hands. They are given gloves to hold the hot pole but they don’t use them. “Gloves don’t offer a good grip,” one of them explains.

Bunty (name changed), 30, says, “These gloves used to be a daily sight until we learnt to

manage without them.” Faiz, 45, chips in, “Earlier when we used to make bangles in coal furnaces, we used to have lung problems. We used to cough a lot. With the introduction of gas furnaces, that problem is behind us.”

The high temperature causes extreme dryness. Workers have to drink water, fruit juice or something cold every half hour to stay hydrated.

They say they eat well at home. “We eat lots of gur (jaggery) and ghee, and non-vegetarian food like siri and paya with lots of ghee. That’s why we don’t feel choked,” says Bunty.

Wages and choices

The factory I am in has 250 labourers. They make around 3,500 todas (huge bunches) of bangles a day. The main and the oldest hand earns around Rs 2,500 a day while other

labourers make Rs 450 to 500.

A manager I meet in another factory says about the latter, “These are daily wagers. They don’t want a monthly job. They are happy making Rs 500 a day. This is a well-accepted system in Firozabad.”

I get to see how plain bangles are decorated with real gold dust. The ornamentation is done with qalam, a brush made with the hair of the furry squirrel’s tail. The more the dust, the higher the bangles cost.

“This (category) is the most expensive of all bangles. There was a time when every woman in Firozabad used to wear these bangles but now they prefer cheaper ones,” Azhar says.

I try my luck at separating them three times and fail, much to the amusement of the women in Azhar’s family, who do it like pros. “It will take a week to learn, madam. You are a city person,” says Seema, a teenager, smiling at me.

Filmi names

Bangle-sellers name their products after film stars — from ‘Madhuri Dixit’ to ‘Karishma’ and ‘Sonam’. I am reminded of Raj Kapoor’s character singing ‘O choodi lele, neeli, kali peeli’ from ‘Paapi’ (1953) as he sells bangles named after the legendary Meena Kumari and Geeta Bali.

The ‘most wanted’ colour in bangles is red, and nearly 75 per cent are made in that colour, I learn.

Azhar takes me to a mammoth factory and shop that belongs to his paternal uncle. All around I see bangles, stacked in heaps four feet high. “The bangles are so delicate. Don’t they slip and break?” I ask.

“No,” the young shop assistant says, grinning at my ignorance. “We tie them so tightly that they don’t break unless you separate them by cutting the thread.” On close scrutiny, I find that the bangles are tied in a weaving pattern.

Tough survival

Families in Firozabad have been making bangles for more than 200 years. But spiralling gas prices, demonetisation and pandemic lockdowns have affected the business in recent years.

The factories came down from about 200 in 2015 to half the number eight months ago. “Now only 14 are functional. A few try to revive their work on and off,” Azhar gives me an update.

Since the smoke from the coal chimneys was affecting the Taj Mahal in Agra, about 44 km away, the government mandated gas instead of coal six years ago. The gas was provided on a subsidy but within a few years, the rates have doubled. Only 5 per cent of the work in bangle-making involves machines and the rest is done by hand.

In March-April 2022, a kilo of gas cost Rs 11, I learn. Within a few months, it rose to Rs 18, and now, it is Rs 40. A 15-day bill for the gas would earlier range between Rs 7 lakh and Rs 8 lakh. Now it is Rs 22 lakh. A furnace burning for 24 hours calls for 3,000 kg of gas.

The cost of raw material is hurting them equally. “Earlier one sack of raw material, which includes soda, ash, arsenic, sand, mica, zinc, and suhaga (borax) used to cost us Rs 1,100. Now it has gone up to Rs 2,600,” Anwar says.

The complex GST rules and the advent of digital payments have impacted small to medium bangle factories, forcing them to run under loss or shut down. “Without a cash economy, retailers aren’t doing well. This business runs on cash, credit and trust,” he says.

I can sense the slump as Azhar’s son ferries me through the bangle market around 4 pm. Flanked by shops, big and small, the market is never ending but the streets are almost empty. “Earlier, these streets used to be so crowded that every day looked like a festival,” his son tells me.

Communal divide

With the BJP being in power, the bangle manufacturers of Firozabad slowly see a rift developing between Hindus and Muslims, who they say never had any feud professionally. The chemical suppliers, I learn, now avoid Muslim bangle makers and prefer to do business with other communities who make glass items like wine bottles.

Despite the friction, the state’s Ganga Jamuna tehzeeb (syncretic culture) remains. Azhar still calls his factory Patel Glass House as a token of thanks to a Hindu who helped his forefathers set it up decades ago. His cousin’s Mahavir Glass Factory gets a Jain name for a similar reason.

As I head home, filled with the warmth of the people of Firozabad, I worry about how our cottage industries are slowly dying. Bangles have existed for two millennia, predating even

Mohenjo-daro, where a bronze statue of a dancing girl wearing a stack of 25 was discovered.

But glass bangles are way cheaper. I think the buyers will remain. I am one of them.

Origins of the city of bangles

Before Firozabad burst onto the scene, glass bangles used to be made 50 km away, in the district of Aligarh, specifically in the small towns of Hasayan, Purdil Nagar, Jalesar and Akrabad. These towns now come under the Hathras and Etah districts in Uttar Pradesh. However, all the labourers used to come from Firozabad.

Roughly 150 years ago, Rustam Ali, a businessman, decided to start bangle-making in Firozabad, where he hailed from. Experienced labourers were available locally, that’s why. He established factories, generated jobs, and soon, Firozabad became a bangle-making hub. Bangle makers visit and pay obeisance to the shrine of ‘Ustad Rustam’ even to this day. However, the third generation of his family is no longer engaged in the business, Azhar, my host, says.

Even today, 90 per cent of the bangle work in Firozabad is done by locals by hand. The rest of the workforce comes from outside and is engaged in packing and ferrying

How glass bangles are made

1. A mixture of sand, soda and chemicals like selenium (used for colouring) are fed into a furnace running at 1,200° to 1,400° C. The mixture melts in about 24 hours.

2. An experienced labourer scoops out a glob of molten glass with a long pole. As the glob cools down, it is rotated manually and given a conical shape.

3. An artisan draws a thin coil of glass from the conical glob and places it on a rod, rotating it steadily, assisted by a motor. It is the most crucial step and also the last at the main

glass factory.

4. Glass coils and the spindles they are wound around are taken to a side yard. Using diamond cutters, artisans separate bangles from another with bare hands.

5. The bangles are sorted for quality and colour, and clusters of 24 and 12 dozens are made.

6. These bangles are open-ended at this stage, and are joined.

7. Some plain bangles are shipped. Others are dispatched for embellishment.

8. Pakai-bhattiwalas smoothen the sharp edges and make these bangles bright and attractive. Many add real gold dust and semi-precious stones, which raises the price by 25 times.

A bunch of 280 to 365 bangles (a muththa) takes 70 hours from scratch to finish. It is divided into clusters, strung together, packed in cardboard boxes, and shipped to domestic and foreign markets.