You could think of Jahnavi (name changed) as a spy. The 22-year-old from a north Karnataka district has saved over 20 minor girls from being pushed into marriage and the Devadasi system. And almost no one in her village knows about her brave detective life.

I came to know about her when she was nominated for a state-level honour. She turned down the nomination. Her reason was simple: If the word got out, her work would suffer.

I collected Jahnavi’s number from her mentor and spoke to her over the phone. The first call ended abruptly when she said, “I am at home. Call me later.” The second time, she said, “I am with friends. I can’t speak now.” With each phone call, my curiosity grew. Over a few months, she did speak to me for brief spurts.

Ten months later, in September 2022, I visited her. Her mentor had told me to reach a community centre in a north Karnataka town. We were received by Jahnavi’s sister near a village bus stand. She spoke about Jahnavi’s efforts to encourage education and self-employment. “Her tailoring classes are popular,” the proud sister said, beaming.

We drove down the village’s dusty roads and past green fields to reach the community centre. Temple bells were ringing across the street as we entered the traditional wade (house), now repurposed into a community space and seed bank.

“Nothing to worry about at this temple,” was Jahnavi’s welcome line. She was a soft spoken girl, dressed in a printed churidar. I got a drift of what she was saying. But I wanted to hear it from her. “Why are you assessing this temple?”

“It’s not about deities, but the people who use the temples to initiate young girls into sexual slavery,” Jahnavi said. Over the years, she has witnessed discreet rituals, where girls are ‘dedicated to God’ in the presence of their parents and a priest. After the ritual, the bride is called a Devadasi and is considered married to the deity. As a result, she cannot marry a human.

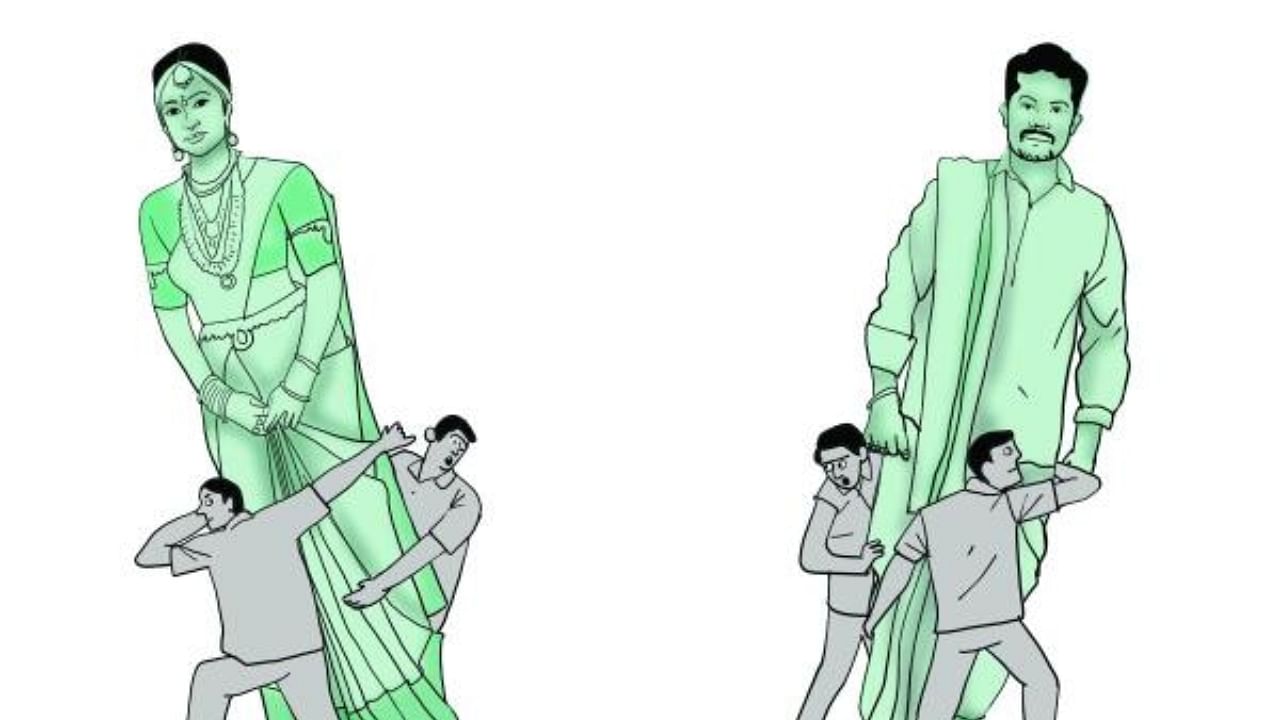

Devadasis are forced into exploitative arrangements. They are forced to have sex with men who don’t even acknowledge the relationship. The men don’t accept children born out of this relationship as their own. What is worse, they walk out as and when they wish. With nothing to cushion her, the girl ends up having relationships with multiple men, one at a time.

“Most men who get into relationships with Devadasis are already married and have children,” said Jahnavi. Though the Devadasi system was banned in Karnataka four decades ago, it still prevails clandestinely in some districts. And that is where Jahnavi’s espionage comes into the picture. The moment she comes to know a girl is being pushed to become a Devadasi, she is out there, working away furiously to stop the ritual.

An ‘escapade’

During the Covid-19 lockdown, Jahnavi came to know about a case. “This 16-year-old school dropout was attending the tailoring class that I had organised. I still don’t know why she chose me, but she came up to me and told me that her parents were forcing her to have a sexual relationship with a stranger after her initiation into the Devadasi system,” Jahnavi said.

The situation was complex, and challenging. “The village had great respect for her parents as they had adopted this girl and taken care of her,” Jahnavi said.

Jahnavi first asked the girl to bring along photos of two articles associated with the Devadasi ritual: a bamboo basket and the muttu. Muttu is a necklace with pearls and beads. It is worn by the girl after the ritual and she is expected to seek alms using the bamboo basket.

In the evening, Jahnavi sent a message to her support group, put together by the civil society organisation Sakhi. The group, with 15 members, provides solidarity to youth facilitators working in villages and urban slums. This on-ground team is made up of people between 18 and 30. They take up different tasks, and spread awareness about agriculture, livelihoods and community empowerment. The group is trained in administrative and legal matters. While the facilitators are given an honorarium to work with the communities, activism is an offshoot for which the organisation provides support.

Jahnavi sent the photos to the group. The team came up with a strategy. Her next task was to take the teenager to the Sakhi training centre, 15 km away, for rehabilitation. In her words: “We discussed an escape plan. The girl left the house casually, boarded a bus, veiling her face with a dupatta. I got into the bus five minutes later. We maintained a distance and were strangers to the outside world. Once she reached the neighbouring town, she boarded an auto and reached the training centre. I followed her in another auto. There, I left her in the safe custody of my support group.”

Jahnavi was running a high fever that day and returned home and fell asleep. Her parents were out in the fields and were not aware of what had transpired. When she woke up in the evening, the teenager’s parents were at the door, accusing her of misleading their daughter. They had seen the girl chatting with Jahnavi. “That was the first time someone suspected my involvement. However, my parents had no clue what I had done and told them they were mistaken,” she said.

After a few days of counselling by the support group, the girl’s parents came around. They were now aware of the shaky legal ground on which they were standing. They agreed to set things right. The girl is now married, and the couple lives with her parents. “I feel happy that she has one partner who will stand by her. She didn’t become a victim of secretive relationships,” she said.

No one in her family knows about Jahnavi’s activist side. “They don’t have to lie when questioned. Also, they won’t worry about my safety,” she said. She also fears any knowledge of her work will compromise her access to information.

In the village, people think Jahnavi is involved in social work when she is not in college. She is a third-year undergraduate student.

That day, I realised why Jahnavi was cutting off my calls suddenly.

From every corner

How does she get leads? The young people she works with get to know what is happening. While they are not aware that she busts child marriages, they know her from her voluntary work, and trust her enough to confide in her. Sometimes, students talk about a classmate missing classes or dropping out. At other times, an overheard conversation at the bus stand or grocery shop is enough to alert her. Also, any celebration, particularly if it is discreet and hush-hush, tells her that something illegal is afoot. And she has a knack for gathering information without triggering any suspicion.

Team-making trick

Once, a fellow villager had come to meet her parents, and started talking about an upcoming wedding. She explained: “They were chatting about the preparations for the wedding of a minor girl. I didn’t utter a word because I wanted to come across as one who didn’t care.”

But she needed the details. She shot a question on wedding shopping and went into the kitchen to make tea. As the conversation continued, she gathered all the details, including the date of the wedding and how the family was going to camouflage it as an adult wedding.

Sometimes, Jahnavi visits the bride’s family and speaks to them on the pretext of helping with the preparations. The primary details she needs are the ages of the bride and the groom, and the date of the wedding.

Modus operandi

Her method is simple. She verifies the girl’s age by talking to people who might know details about her school and class. In some cases involving minor girls, parents produce fake age certificates. Not even in one instance has she found a minor groom.

And then, Jahnavi gets busy on the phone.

She texts or calls the support group, which passes on the information to ChildLine 1098. If she comes to know about a ritual already in progress, she calls the helpline directly. “In both situations, the team arrives quickly. I am usually elsewhere when the action takes place,” Jahnavi said.

She deletes all call records and messages immediately. This is how she has ensured that no one outside the support group knows about her work. “The delete option saves me every time,” Jahnavi said, flashing a smile.

How it all began

For her, like it was for other girls her age, weddings were about food, clothes and celebrations. But that was only till she turned 16. One of her classmates got married when she was in Class 8. “It was so much fun,” she said. But the friend discontinued studies in Class 9.

“I realised that early marriage means giving up on many basic rights including education. It snatches our freedom to dream,” Jahnavi said. This prompted her desire to become a crusader. But she didn’t know how to go about it. Two years went by as she was figuring out a way. That was when she came into contact with Sakhi, which works with young people in rural areas.

During an orientation session, she heard about the child helpline and how anyone could dial the number to save a child from exploitation. “From that day, I started looking at every wedding in the village with a different lens,” she said.

Despite the training, her first effort was traumatic. She called 1098 when she came to know about a wedding. “I was terrified people in the village would know I was behind the busting,” she said. Her stress peaked when the ChildLine 1098 team arrived at the village. Her biggest fear was that they would mention her name. Only later did she come to know that ChildLine 1098 doesn’t reveal the complainant’s name.

Jahnavi was 18 when she prevented a child marriage for the first time. In the four years since, she has successfully stopped every child marriage in her village. Elsewhere, the number of such marriages peaked during the pandemic, she said.

Mixed feelings

How do the brides respond when an underage marriage is stopped? Some feel low and curse whoever is responsible for the police action. “But I notice a sense of relief in many,” Jahnavi said.

Earlier, calling off a wedding would result in isolation of girls from friends and family, but now they continue in school. “The situation has improved to that extent,” Jahnavi said. Some rescued girls have taken up tailoring, others are employed in offices and factories in nearby towns. A small number is pursuing higher studies. “I know of a few who got married after they turned 18 and became homemakers,” Jahnavi said.

The fight against child marriage takes many forms. Not all girls are so secretive. Some are upfront about their work as child rights activists. They speak to the brides’ parents before calling ChildLine 1098. Some activists join the ChildLine 1098 team during the rescue.

Jahnavi prefers the undercover role. “This has helped her stop almost every early marriage that she has come across, and that is a rare feat,” said her mentor.

Why her work matters?

Grassroots reporting of abuse against children is a sign of progress. This is the result of decades of advocacy by government agencies and civil society organisations. Children and youth are becoming increasingly aware of their rights and duties. They are working together to create a child-friendly ecosystem. People who report from the ground are the eyes and ears of ChildLine 1098. The ChildLine 1098 team, which comprises police personnel, members of the district child protection unit, and government officials, handles every case carefully and sensibly. Not revealing the source is key. — Vasudeva Sharma, Child rights activist

Around Belagavi

The Devadasi system is followed by some socially and economically deprived communities in north Karnataka.