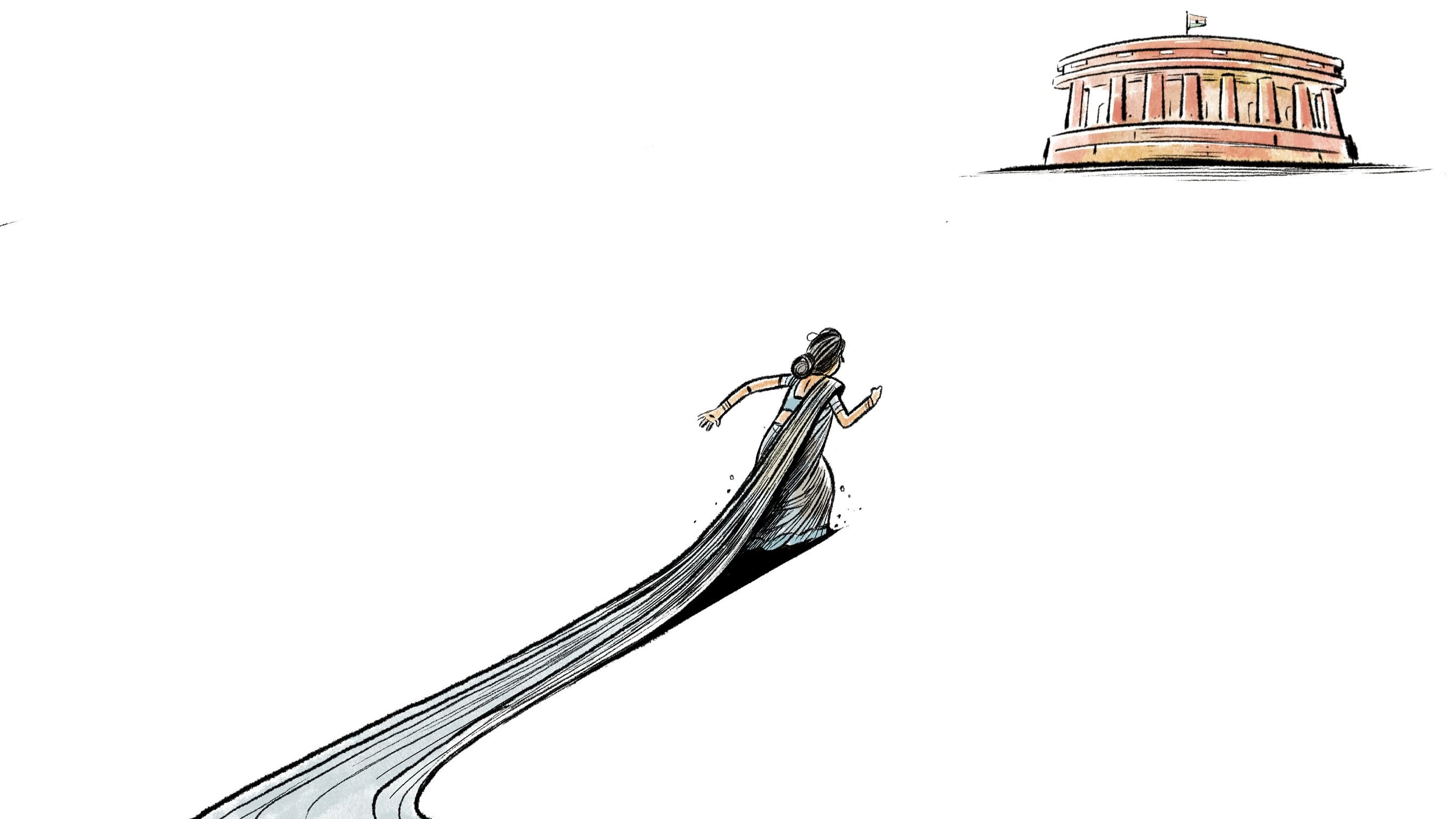

DH Illustration

Sajith Kumar

On 22 August 1936, Congress leader Ammu Swaminathan wrote to Jawaharlal Nehru, the party president, asking for the list of women candidates to represent the party in the 1937 elections. Attaching a copy of the All-India Women’s Conference (AIWC) manifesto, Candidates for the Coming Election, she highlighted ‘Women make a special contribution to the general welfare and progress of the country.’ Further, she drew attention to the absence of women members in the Congress Working Committee (CWC) — the highest decision-making body of the Congress. Ammu demanded that Nehru appoint at least one woman in the CWC with immediate effect.

In his response, Nehru wrote that women will be naturally fielded from the seats reserved for them. However, no commitment was made about fielding women from the general seats. The struggle for adequate representation of women in politics is a tale as old as time.

A decade later, the Constituent Assembly was created to formulate a Constitution that reflects the dreams and aspirations of the people. Although the Assembly was meant to be a microcosm of India, certain sections of the population were not adequately represented. Only 15 women were members of this distinguished body of 299 members. Though a mere five per cent, they have left lasting imprints.

Sparsely remembered

Some of these women were battle-hardened veterans who had resisted patriarchy and colonial rule to win famous victories and were continually striving for equity. Others were passionate ideologues keen on pushing the envelope of justice and progress. These women and their compatriots ensured a fairer and more equal Indian Republic, yet their contributions are sparsely remembered and their struggles appropriated.

As we celebrate more than 75 years of freedom, there is a renewed interest in the Constitution. It is at the heart of public discourse — be it election speeches, on the floors of the parliament, or in public spaces. A host of contemporary questions are answered by looking at the past. Often, this takes the form of obsessive focus on the actions and speeches of key historical figures like Jawaharlal Nehru, Dr B R Ambedkar, B N Rau, and Rajendra Prasad. This approach ignores the contributions of several other leaders and invisiblises the different social movements that were crucial in forging today’s India. The women leaders are one such group whose contributions to nation-building remain forgotten.

The struggle for the right to vote

A classic example of how women have been invisibilised in our history comes from the discourse on the right to vote. To showcase the progressive nature of our polity, it is often claimed that the Indian Constitution has easily ‘granted’ women the right to vote. This line of thinking completely ignores the relentless struggles women activists undertook for decades.

In 1917, Ammu Swaminathan, a future member of the Constituent Assembly, joined hands with prominent leaders such as Annie Besant, Malathi Patwardhan, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, and Margaret Cousins to set up the Women’s Indian Association (WIA). WIA aimed to address the many socio-economic challenges faced by women including child marriage, the devadasi system, widow remarriage, divorce, and inheritance, while also working towards expanding equal educational and economic opportunities. It was also India’s first national body to advocate for female suffrage.

The same year, Britain formed the Montague-Chelmsford Commission to formulate a report on how to introduce self-governing institutions in India. It was to prepare a list of reforms which would form the basis of the Government of India Act 1919. The WIA was part of a combined women’s delegation led by Sarojini Naidu that met the Commission and demanded the Indian women’s right to vote. Indian suffragists intensified their advocacy, travelling to Britain to garner support. In 1918, Sarojini Naidu took the women’s rights issue to the Congress party, moving resolutions for women’s enfranchisement at Congress sessions in Bijapur and Bombay. In her speech, Naidu demanded that when discussing the rights of citizenship, the word ‘man’ must include women as well.

They earned a substantial victory with the enactment of the Government of India Act 1919 which allowed provincial legislatures to enfranchise women. Over the next few years, Madras, Bombay, and the United Provinces recognised women’s right to vote. But it was guaranteed conditionally only to those women who owned property, earned an income, or met other criteria. The majority of women were excluded and still did not have a right to sit in legislative bodies. They demanded universal franchise which was acknowledged by the All-Parties’ Conference in the Nehru Report of 1929.

In the early 1930s, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur led a delegation of women leaders to the League of Nations in Geneva. Ammu Swaminathan was also present. They advocated for women’s suffrage. It received widespread coverage. Soon after, the Government of India Act 1935 was passed granting women aged 21 years and above the right to vote nationally. This law enabled as many as six million Indian women to vote and contest elections to both general seats and the seats reserved for women.

A new wave of women leaders

The 1936-37 elections were historic as they brought forward a new crop of women leaders. Conservative sections of society didn’t take to it happily. The hatred received by Begum Qudsia Aizaz Rasul for her candidature is worthy of mention.

Qudsia and her husband were both candidates but unsurprisingly she faced a tumultuous campaign. Religious leaders were not amused by her candidature and issued a fatwa. They declared it un-Islamic to vote for a non-purdah Muslim woman. Their anger was not only due to her disregard for purdah but also that a woman had dared to openly compete with men. Qudsia ran a spirited campaign and won the election with a thumping majority. Her victory was also significant as she contested for a general seat (a seat not reserved for women). Across the country, only ten women had won from general seats.

Other Constituent Assembly colleagues who won the election were Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit and Hansa Mehta. Mehta’s brush with traditionalists happened when she decided to marry outside her caste. She was threatened with excommunication from her community but she didn’t cow down.

Sexism at every step

Patriarchy was omnipresent in the lives of these women leaders but they persevered. Leela Roy faced resistance when she joined Shree Sangha, an all-male armed revolutionary group. Despite the sexism at every step, she led the organisation in critical times. Malati Choudhury didn’t give up her desire to study at Tagore’s Visva-Bharati which was an all-male university. Her unprecedented request opened the doors of the university for all women students. Sucheta Kripalani faced various difficulties as the lone woman student at St Stephen’s College, Delhi.

Additionally, the young women leaders were often at odds with senior women activists. Renuka Ray faced criticism for advocating for the right to divorce and women’s right to an inheritance. Similarly, Mehta was against demanding incremental reforms and advocated for interventions that struck at the root of the inequities. At the Constituent Assembly, Mehta was a member of the fundamental rights sub-committee, alongside Rajkumari Amrit Kaur. Mehta and Kaur fought to dilute the scope of the right to religion and appealed to incorporate a uniform civil code as a fundamental right. The social reform agenda the women championed was often at odds with religious practices, therefore, they were wary of an unfettered right to religion and wanted strict adherence to a secular civil code.

G Durgabai brought an amendment to reduce the age of Rajya Sabha membership to 30 years instead of the original 35 years. Her amendment was supported by various leaders and later accepted. Vociferous advocates of the Hindu Code Bill, Durgabai and Renuka Ray were very disappointed with the continued delay in the passage of the Bill. They went to Prime Minister Nehru with their complaint. He patiently listened and assured that the progressive laws would be passed after the first elected government was formed. And he kept his word.

Shaping global order

Indian women leaders helped mould not only our Constitution but also shaped the global order. Mehta played a crucial role in ensuring the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted gender-neutral language. It was at her insistence that the draft was changed from ‘all men are born free and equal’ to ‘all human beings are born free and equal’. Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit had a celebrated diplomatic career and made history when she became the first woman to head the UN General Assembly.

In administration too, the women leaders were ahead of their time. As an Allahabad Municipal Board member, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit started a milk scheme to address malnutrition among children. This was one of the first recorded instances of a mid-day meal programme. When she became a minister in 1937, Pandit increased budget allocations for healthcare and laid special emphasis on developing maternity and childcare services.

A decade later, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur took charge of the Union Health Ministry and became independent India’s first woman cabinet minister. Kaur laid the foundation of the public healthcare system and was instrumental in the creation of India’s premier medical institute, AIIMS. Pandit’s and Kaur’s administrative experience paved the way for other women leaders: Annie Mascarene and Renuka Ray — ministers in state governments; Durgabai Deshmukh — a founding member of the Planning Commission; Sarojini Naidu — the first woman governor; and Sucheta Kripalani — the first woman chief minister.

These fifteen women contributed immensely to shaping modern India. They navigated extraordinary challenges and left lasting imprints. Each of their remarkable journeys not only tells us about law and polity but also presents a glimpse into the multiple Indias that existed — in their perfections and imperfections.

(The writers are authors of the book, The Fifteen: The Lives and Times of the Women in India’s Constituent Assembly, published recently by Hachette India.)