In Waco, Texas, Lily Coffman, 15, donned her handmade “RBG” coronavirus mask and “dissent collar” earrings Saturday night and joined a small crowd of mostly mothers and daughters in a candlelight vigil at the county courthouse. There, they held an 87-second moment of silence — a second for each year of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s life.

In Denver, Sheena Kadi, 38, who describes herself as a “queer Arab millennial woman,” was making chicken soup Friday night when she learned of the justice’s death. “I walked over to my desk, lit my RBG candle, opened a bottle of Barolo and cried,” she said.

In Danbury, Connecticut, Bonnie Rubenstein Wunsch, 59, was helping to run her synagogue’s Rosh Hashana service over Zoom on Friday night when she heard the news. She has been comforted, she said, by a post circulating on social media: In the Jewish tradition, someone who dies on the holiday is considered a zaddik — a righteous person.

For these women and so many others around the country, the loss of Ginsburg brought on a very particular kind of grief. It was not the grief of liberals agonizing over President Donald Trump’s pronouncement that he intended to quickly fill the justice’s seat and the possibility of long-term conservative domination of the Supreme Court, though there was plenty of that.

It was also the loss of an elder stateswoman of feminism, a powerhouse octogenarian who had become an unlikely icon to women of all ages, and especially the millennial set. For many women, and many girls, it was also a deeply personal loss.

In Denver, Kadi, who has worked in AIDS activism, said Sunday that she did not quite understand herself why the justice’s death had brought forth such tears. She recalled a reception in the winter of 2015 after the court’s landmark decision making same-sex marriage legal throughout the country. The room was packed with people.

In the middle was Ginsburg, looking much smaller and more frail than Kadi had imagined. What the justice said to her, Kadi said, sticks with her to this day: “She told me that I may not ever understand the depth and breadth of the impact from my organizing and activism, and that it was important that when I get tired or frustrated,” that even when it seems as if progress toward equality is stalled, “to remember that it is progressing forward.”

As only the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court and a fierce advocate for women’s rights, Ginsburg burst into popular culture and became an internet sensation after a law student proclaimed her the Notorious RBG, a play on the nickname of a famous rapper. She was the subject of two movies: a fictionalized drama of her early life in which she juggled work and motherhood, and a documentary that let women into her personal life as a wife, mother and grandmother.

“As women, it’s not that we don’t have role models, but role models like RBG come along so very rarely,” said Jordan Jancosek, 31, an archivist at the Brown University library in Providence, Rhode Island.

“And it wasn’t that she was a feminist icon and she did so much for women and was such a fighter for people to not discriminate based on your sex,” Jancosek went on, “but she understood that both men and women were being beholden to these restrictions and these ways that society had put on them, and she really took it on as her duty to turn that on its head.”

Many were struck not only by her professional accomplishments but also by her relationship with her husband, Martin Ginsburg, who died in 2010 and had no problem letting his wife take first billing.

“However cliché it may be, she was really one of the first people who I saw and said, ‘A woman really can have it all,’” said Jane Bisson, 24, a 2018 graduate of Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, who works in public affairs and crisis communications in Boston.

That is not to say Ginsburg drew no criticism or that her legacy was perfect. She offended Black women (and men, for that matter) in 2016 when she said she thought it was “really dumb” for Colin Kaepernick, at the time the San Francisco 49ers quarterback, to kneel during the national anthem. She later apologized to Kaepernick, saying she had been “inappropriately dismissive and harsh,” but for some the wound is still raw.

Jennifer Allison, a Black social justice activist in Washington, wrote on her Facebook page that lionizing Ginsburg without acknowledging such comments would “perpetuate more harm and uphold white supremacy.” But Jeannette Mobley, 75, a Black Democratic activist in Washington, defended the justice, saying, “She was woman enough to come back and apologize for it.”

In speeches and public appearances, Ginsburg touched the lives of numerous women. Wunsch is the executive director of Alpha Epsilon Phi, a Jewish sorority that Ginsburg joined while an undergraduate at Cornell University. She heard Ginsburg speak four years ago, in the heat of the 2016 election, after the justice had been criticized for calling Donald Trump “a faker” — words she later said were “ill-advised.”

Wunsch took notes, which she looked at Sunday. One quote stuck out: “You can disagree without being disagreeable.”

Ginsburg, of course, was famous for disagreeing and may be remembered as much for her judicial dissents as for her majority opinions.

In Texas, Coffman, who attended the vigil with her own mother, said that she was considering a career in law and that Ginsburg was a “role model in that sense.” She admires Ginsburg for “making her voice heard, even if it’s not the majority opinion.”

Fern Pasternak, a 23-year-old accounting student in New York, carries her Notorious RBG tote bag — the one with the bespectacled justice wearing the white lace “dissent” collar that she adopted to bring her judicial robe a touch of femininity, and a crown sitting cockeyed on her head — on the Long Island Rail Road as she commutes from her home in Wantagh to Manhattan, where she attends Baruch College.

She holds up Ginsburg as the kind of professional woman she wants to be.

“Once I graduate I will be working at a big accounting firm, and those companies especially have had so many issues with gender diversity, and women not having positions of power, and women being shut down by men,” Pasternak said. “I don’t want to be another story. I want to be the story of a person who stands up to that oppression or that bias.”

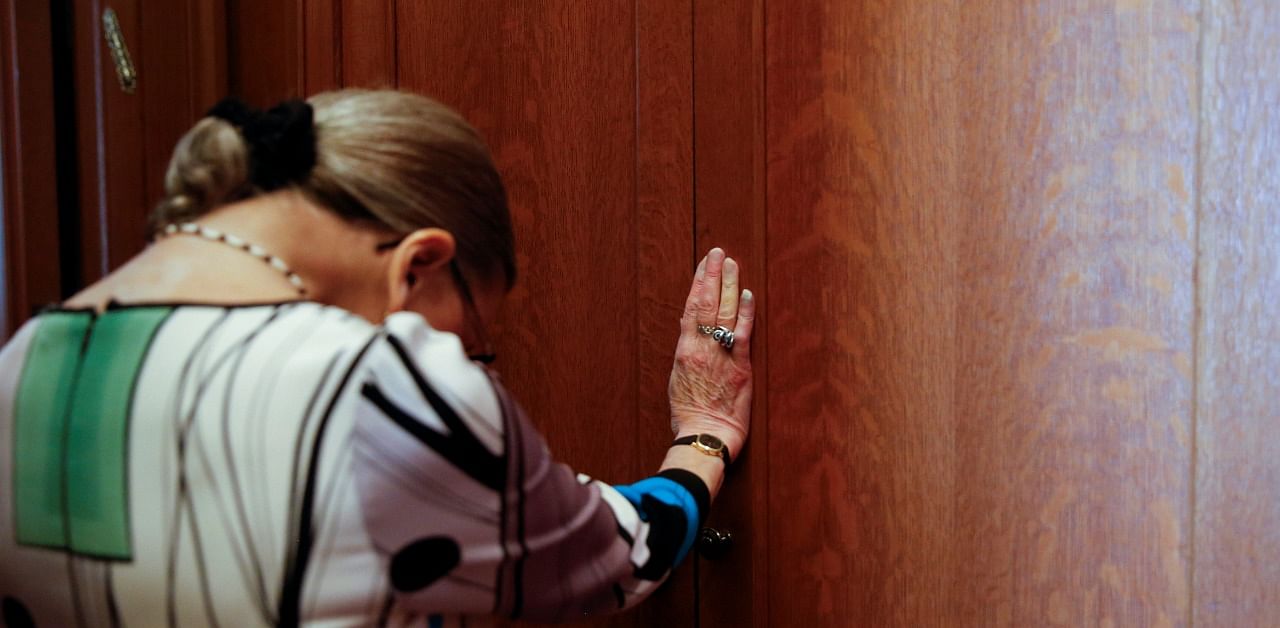

Lexie Wackman, 9, of Washington, was just 6 when she had her introduction to Ginsburg. Her mother, Tunde Wackman, bought her a copy of “I Dissent,” a children’s book about the justice, which prompted her to give a speech about Ginsburg to her fellow first graders. Lexie burst into tears when she heard that the justice had died, and Wackman encouraged her daughter to write a note, which they left on the steps of the Supreme Court on Saturday.

“Ruth,” she wrote, dismissing with the customary honorific, “I always dreamd of being an actavist like you. I read your book many times and my insperation for you never changed. I thought you could NEVER die.”