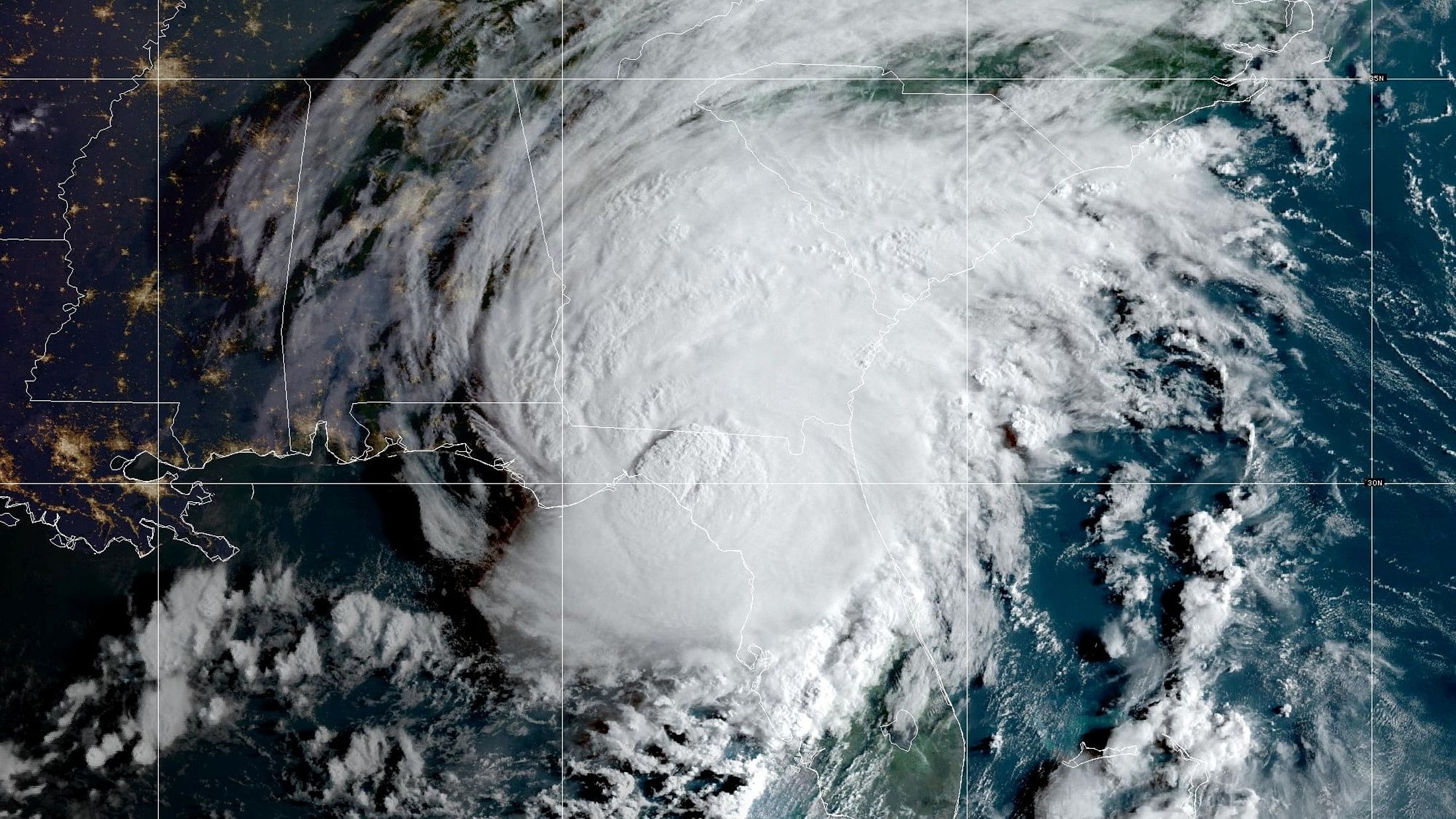

Representative image of a hurricane.

Credit: Reuters Photo via Noaa

While the eye of Hurricane Franklin was expected to stay well away from land, Bermuda faced tropical storm conditions on Wednesday. And the storm was producing “dangerous” surf and rip currents along the East Coast of the United States and will continue to do so for the next few days, the National Hurricane Center said.

Franklin weakened to a Category 2 on Wednesday from Category 4, but it was expected to remain a hurricane through the rest of the week.

As of 11 pm Eastern, Franklin was about 160 miles north of Bermuda and moving east-northeast at 14 mph, the hurricane center said in an advisory. Bermuda was under a tropical storm warning, and the center said tropical storm conditions were expected on Wednesday.

Franklin was producing maximum sustained winds of about 100 mph, the Hurricane Center said, making it a Category 2 storm on the five-tier wind scale used to measure tropical cyclones in the Atlantic, the center said.

Life-threatening surf and rip currents from the storm were expected to affect Bermuda and the East Coast of the United States in the coming days. Some beaches on Long Island, New York, closed amid rip currents and dangerous surf conditions, and at least one beach along the New Jersey Shore was closed, the local news media reported.

“With tropical storms and hurricanes affecting our beaches on Long Island, we are taking proactive steps to protect New Yorkers, and I urge everyone to remain vigilant,” Governor Kathy Hochul said in a statement.

The Hurricane Center said that Franklin was expected to speed up as it progressed through the Atlantic Ocean.

Franklin was blamed for at least one death in the Dominican Republic, and hundreds of thousands of homes were without power or potable water last week. At one point, 350,000 homes were without power, and more than 1.6 million did not have potable water.

The Atlantic hurricane season started June 1 and runs through November 30.

In late May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that there would be 12 to 17 named storms this year, a “near-normal” amount, forecasters said. On August 10, NOAA officials increased its estimate to 14 to 21 storms.

There were 14 named storms last year, coming on the heels of two extremely busy Atlantic hurricane seasons in which forecasters ran out of names and had to resort to backup lists. (There were a record 30 named storms in 2020.)

This year features an El Niño pattern, which started in June. The intermittent climate phenomenon can have wide-ranging effects on weather around the world, and it typically impedes the number of Atlantic hurricanes.

In the Atlantic, El Niño increases the amount of wind shear, or the change in wind speed and direction from the ocean or land surface into the atmosphere. Hurricanes need a calm environment to form, and the instability caused by increased wind shear makes those conditions less likely. (El Niño has the opposite effect in the Pacific, reducing the amount of wind shear.)

At the same time, this year’s heightened sea surface temperatures pose a number of threats, including the ability to supercharge storms.

That unusual confluence of factors has made making storm predictions more difficult.

There is consensus among scientists that hurricanes are becoming more powerful because of climate change. Although there might not be more named storms overall, the likelihood of major hurricanes is increasing.

Climate change is also affecting the amount of rain that storms can produce.

In a warming world, the air can hold more moisture, which means that a named storm can hold and produce more rainfall, as Hurricane Harvey did in Texas in 2017, when some areas received more than 40 inches of rain in less than 48 hours.