Voting in California is not just a matter of plumping for Trump or Biden -- residents are confronted with scores of other decisions in a bewildering array of referendums and for officials ranging from judges to school boards.

The largest state in America by population holds elections that mix direct local democracy with politics that is heavily influenced by powerful lobby groups.

In total, nearly 380 referendums will be held on November 3 across California, in addition to electing the president and all the "down-ballot" officials.

"Usually I just show up at the voting booth and I read a small amount and I vote one way or the other. About halfway through, I feel guilty about not really understanding it," admitted Kathy Otterson, a telecoms manager who lives in Berkeley, California.

"But this year, I have lots of time and I am home voting. My husband and I made a date out of it, so we went to lunch and we ran through it," she told AFP.

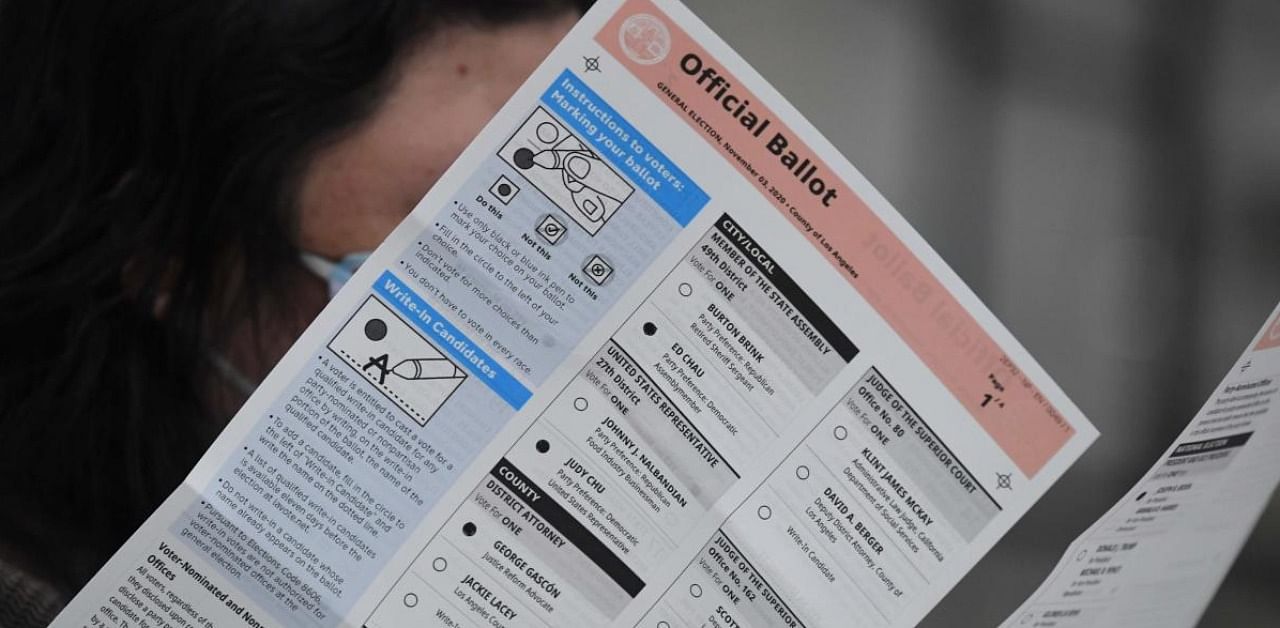

Otterson faces 45 different decisions -- including 25 referendums -- on a seven-page ballot paper, plus a thick booklet of manifestos written in dense, small type.

Almost $750 million has already been spent on campaigns for the 12 state-level referendums known as "propositions" in California, making it the second most expensive political exercise in the United States after the presidential election.

With an economy bigger than Britain, France or Italy, California's state politics are serious business.

This year, the vote on "Proposition 22" will be followed closely nationally, and around the world.

It will determine if Uber and Lyft drivers are self-employed "independent contractors" or salaried employees -- a key battleground of the modern gig economy.

The other referendums range from rent control issues and dialysis clinic regulations, to stem cell research and voting rights for prisoners on parole and 17-year-olds.

With many people overwhelmed by the choice, action groups offer guides on how to vote along your political inclinations.

The feisty "League of Pissed off Voters" advises left-wing progressives in San Francisco how to go through the ballot, rating each option somewhere between "Hell Yes," "Hell No" or "Conflicted."

"It is very clearly left-leaning, but they had fair, factually-based information about each proposition and each candidate," said 30-something Dawn Rose. "It was like 20 pages of information instead of 200!"

Rose's companion Dave said that finding a way through the maze seemed an important civil duty after Donald Trump's divisive first term.

"We already delegate a lot of our power to our state representatives," he said. "It makes me feel good to feel like I have a voice and say in the world that we live in."

But California's democracy is also accused of being open to exploitation by companies determined to protect their interests, or even to circumvent laws passed by elected officials.

The "Proposition 22" vote is a response to a new state law which would force taxi app companies like Uber to register their drivers as employees and pay them social benefits.

The campaign to vote "yes" to exempt the firms has already spent nearly $200 million on their cause.

The referendum is set to become the most expensive in the state's history, ahead of one in 1998 on the right to open casinos in Native American territories, according to David McCuan, professor of political science at Sonoma University.

"If you're trying to get a 'yes' vote... you have to spend early and often," he said, adding that most referendums are rejected by voters.

"(But) if the campaign rises and is visible and strong in California, there's a spillover effect to other states -- that is what's so important here."

Lobbyists make strenuous efforts to secure public support -- mailboxes and social networks are currently engulfed by messages such as "Mothers Against Drunk Driving endorses YES on 22."

"It's a huge business," says McCuan, explaining that companies are being paid up to $8 per signature to gather individuals who back an issue being put up for a future referendum.

Despite all the lobbying, few campaigns make it from conception to success.

California, known as a liberal bastion, voted twice against same-sex marriage -- in 2000 and 2008 -- before it only really became commonplace after a long battle in the courts.

The referendum route is "problematic as it's used too much," said Eric Schickler, professor of political science at the University of California, Berkeley, adding the concept was historically developed as a way to bypass corrupt legislators.

Nowadays "the place where you want to be able to use propositions is where the legislature's making decisions about themselves," he said.

Voter Kathy Otterson cannot make up her mind on Proposition 22, but she is clear about Proposition JJ -- on increasing the local mayor's salary.

"I said yes, because I think they should have enough money to live."