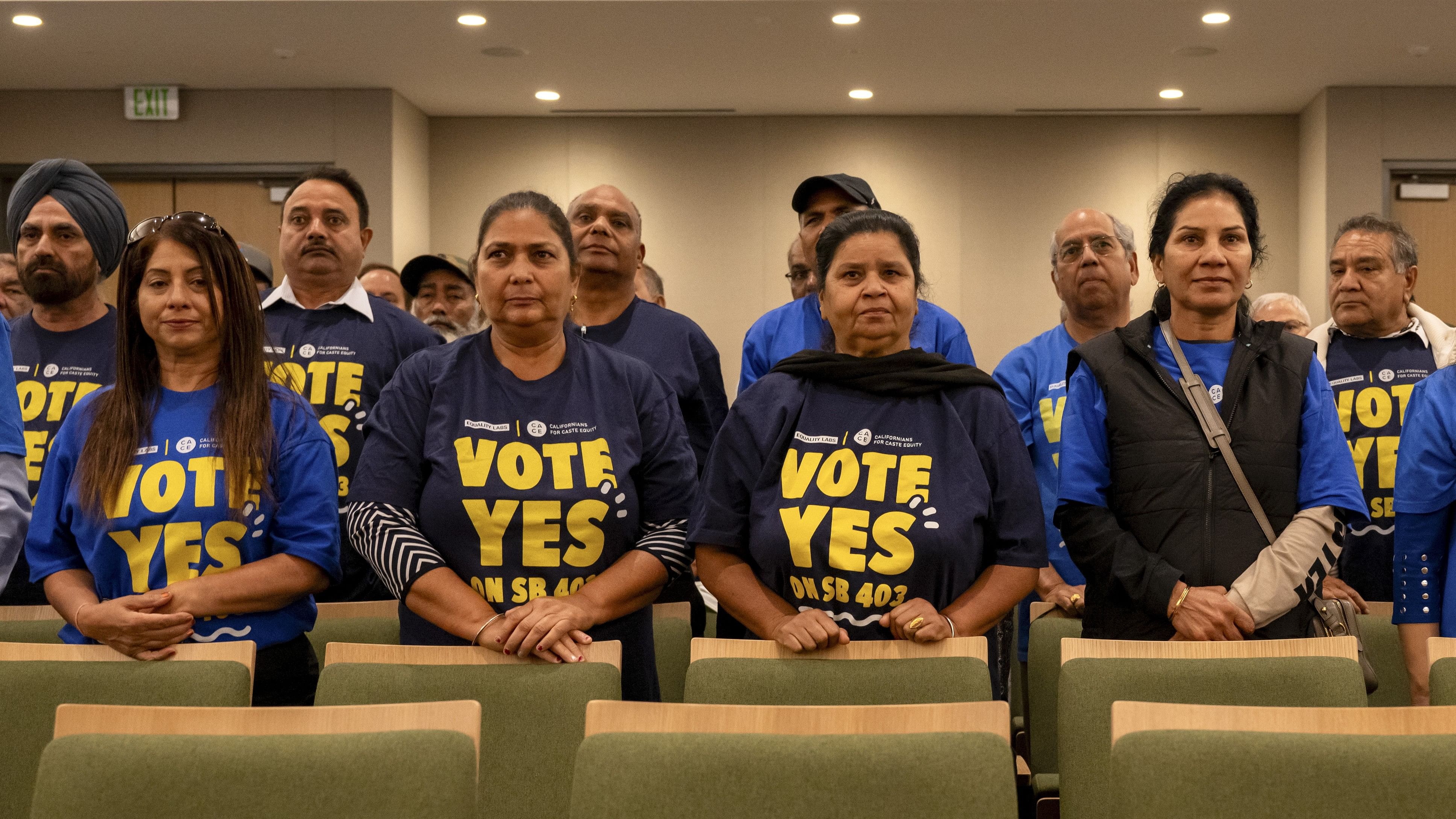

Supporters of Senate Bill 403, which would ban caste-based discrimination, in the State Assembly in Sacramento in August.

NYT Photo

It’s an ancient system of social stratification that emerged in India thousands of years ago.

It is also a term that has driven intense debate — and divisions — within the growing South Asian community in California recently, especially in Silicon Valley, where South Asians comprise a significant share of the workforce.

On Thursday, Fresno officially became the first city in California, and the second in the country, to enact a ban on discrimination based on caste. Seattle passed a similar ordinance earlier this year.

And any day now, Gov. Gavin Newsom could sign a bill on his desk that would make California the first state in the nation to explicitly ban caste discrimination. The governor has until Oct. 14 to sign or veto the bill, known as Senate Bill 403.

“We need this bill,” Nirmal Singh, 42, an Indian American doctor from Bakersfield, California, said in a recent interview. Singh is one of a group of South Asian activists who have been on a hunger strike outside Newsom’s office since early September.

During a reporting trip in the Bay Area last month, I spoke with more than a dozen people who, like Singh, identify as Dalits, a historically oppressed community who are considered not just lower caste, but outcaste — what used to be called untouchable. Many of them told me about encounters they had with caste-based bigotry in the United States, in the forms of wage theft, housing discrimination, mistreatment in the workplace or social exclusion. They said that explicitly defining caste in state law will give people like them reassurance to come forward with their stories.

But the bill has also met with fierce opposition. Some South Asian Americans say that the proposal unfairly targets Hindus, because the caste system is most commonly associated with Hinduism. They also say that existing laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of religion and ancestry are sufficient, and they point out that caste discrimination was outlawed in India more than 70 years ago.

Praveen Sinha, a professor of accounting at California State University, Long Beach, filed a lawsuit last year challenging the university system’s addition of caste to its discrimination policy. Sinha said he was concerned that the addition would make South Asians like him more vulnerable to unfair accusations of discrimination.

“I don’t want to be having this sword hanging over my head,” he said.

For decades, the South Asian diaspora was composed mainly of upper caste people, in part because they had greater access to the resources necessary to qualify for skilled worker visas. More recently, though, affirmative action policies in India have allowed more people from oppressed communities to attend universities and move abroad.

The issue burst into the public conversation in 2020 when California’s Civil Rights Department sued Cisco Systems, accusing two of the company’s engineers of caste discrimination. The state dropped its case against the two managers at the heart of the Cisco matter earlier this year but is still suing the company.

The lawsuit was initially filed just after the death of George Floyd set off a national conversation about systemic discrimination. Awareness of caste discrimination has grown since then, and several universities and companies have added caste to their discrimination policies.

“The more diverse California becomes, the more diverse our laws have to be, and the further we have to go to protect more people,” Aisha Wahab, a Democratic state senator who introduced the bill, said in an interview.