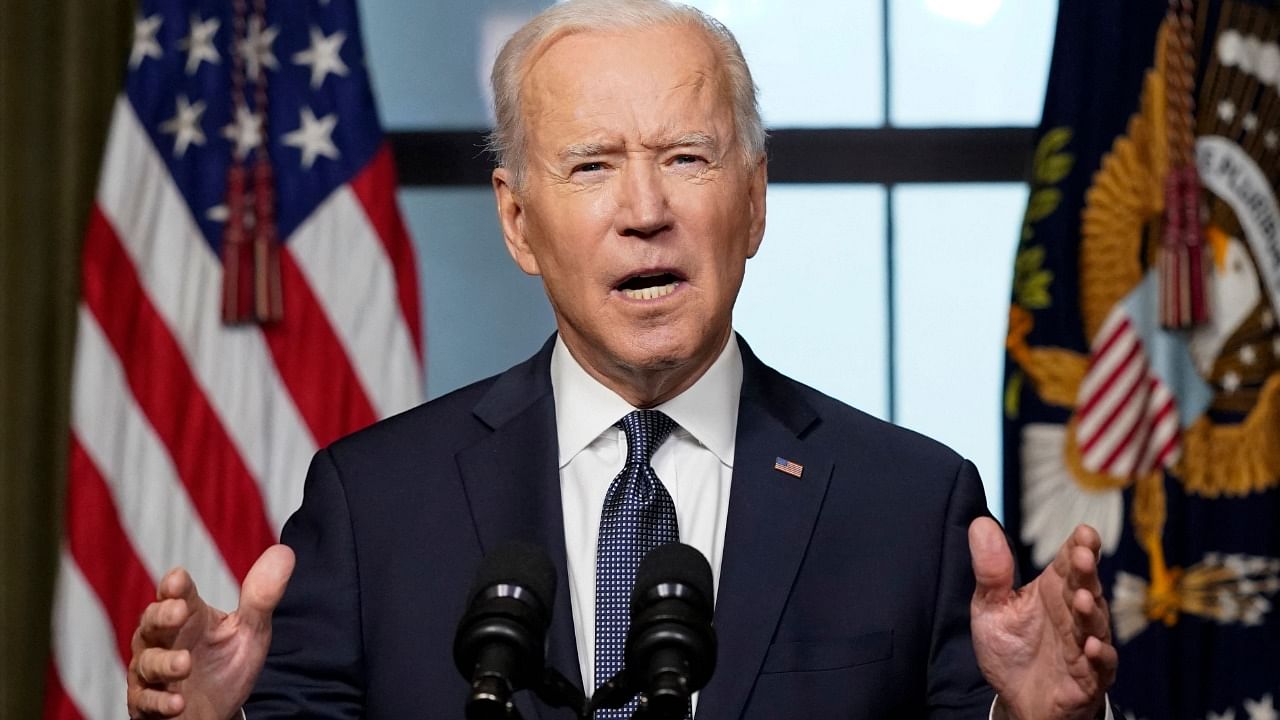

It took 15 minutes for President Joe Biden to announce the end to a forever war, standing at a lectern in the White House Treaty Room — the same place where George W. Bush had announced airstrikes on Afghanistan 20 years before, less than a month after the Sept. 11 attacks. The symbolism of Biden’s choice of venue was as heavy as the two brocaded flags that stood behind him. Both presidents were speaking to a mourning public, but in very different circumstances.

The language each president used was telling, framing the war in his preferred terms and mirroring the mood of the republic. In beginning the war, Bush exuded a calm that in retrospect looks almost buoyant — channelling the confidence of a country that had outlasted its rival in the Cold War and could barely fathom a major setback to its enormous power. Biden’s speech was necessarily more chastened and straightforward in its rhetoric and its overall message.

Where Bush talked of fulfilling a mission, Biden talked about painstaking and unglamorous work. His tone was sober and sombre. The only time he mentioned the word “peace” was in the context of “peace talks” — talks that the United States would not be a party to but would obligingly “support.” It was a notable turn. The word “peace” has long exerted an almost talismanic appeal for presidents; even Richard Nixon kept turning to the phrase “peace with honour” when he announced the withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam in 1973.

But Biden’s speech wasn’t about peace because it wasn’t about victory, even if Biden suggested that the country’s “objective” and “goals” had been achieved with the killing of Osama Bin Laden 10 years ago and a “degraded” Qaeda presence in Afghanistan. Instead of “winning” or “losing,” what Biden was offering instead was a diversion of resources — from the maw of Afghanistan to other operations that would wend their way across the world. The metaphor he used for the diffusion of the terrorist threat was “metastasising,” and the future he presented was not one of clashing armies but of “cyber threats.” Biden sounded like the physician who gravely informs you that the drastic surgery you had hoped would deliver you from your chronic condition simply wasn’t going to work.

“We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for the withdrawal and expecting to get a different result,” Biden said. There was an exasperated cadence in his voice, an exasperation sharpened, not softened, by grieving — by a president who had lost a wife and a daughter nearly five decades before and his son Beau in 2015.

“I am now the fourth American president to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan,” Biden said. “Two Republicans. Two Democrats.” The bipartisan gesture was classic Biden, a suggestion that he was part of a lineage, but in his speech he also made it clear what made him different from the rest. “I am the first president in 40 years who knows what it means to have a child serving in a war zone,” Biden said. “Throughout this process, my North Star has been remembering what it was like when my late son, Beau, was deployed to Iraq.”

Like any televised announcement from the White House, this one contained its share of bland generalities — what the “humanitarian work” Biden promised might entail, for example, or precisely how he expects to “strengthen our alliances” and “ensure that the rules of international norms” are “grounded in our democratic values.” But when the subject turned to grief, Biden became forceful and specific. Taking a card from his jacket pocket that he said he had been carrying for the last 12 years to remind him of the number of troops killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, Biden insisted on an “exact number, not an approximation, not a rounded-off number, because every one of those dead are sacred human beings who left behind entire families.”

By invoking those families, Biden was showing how much had changed. (He gave a speech last month saying that he kept a card in his pocket with the number of pandemic deaths, too.) Twenty years ago, Bush ended his address by quoting a letter he had received from a fourth-grade girl whose father served in the military. “As much as I don’t want my dad to fight,” she wrote, “I’m willing to give him to you.”

Bush marvelled at what he called this “precious gift,” but today the anecdote doesn’t sound so much heartening as heartbreaking. The girl was writing at a time when some of the people now serving in Afghanistan hadn’t even been born — a fact that Biden arrived at towards the end of his 15 minutes, when he pointed out that the war had become a “multigenerational undertaking.”

By turning to that deflating word — “undertaking” — Biden was perhaps inadvertently echoing its variant, the undertaker who makes preparations for the dead. Compared to the template of presidential speeches, it’s easy to say what Biden’s speech was not — not rousing, not triumphant, not even particularly hopeful. What it was, though, was Biden in full: as weary and exhausted as the public he was elected to serve.