For hundreds of years, through plagues and other pandemics, people used to believe that disease was spread not through droplets or flea bites, but through the inhalation of unpleasant odors. To purify the air around them, they would burn rosemary and hot tar.

These scents, wafting through winding streets of London, were so common during the Great Plague of the 17th century that they became synonymous with the plague itself, historians said.

Now, as the world confronts another widespread outbreak, a team of historians and scientists from six European countries is seeking to identify and categorize the most common scents of daily life across Europe from the 16th century to the early 20th century and to study what changes in scents over time reveal about society.

The $3.3 million “Odeuropa” project, which was announced this week, will use artificial intelligence to sift through more than 250,000 images and thousands of texts, including medical textbooks, novels and magazines in seven languages. Researchers will use machine learning and artificial intelligence to train computers to analyze references in texts to smells, like incense and tobacco.

Once cataloged, researchers, working with chemists and perfumers, will recreate roughly 120 scents with the hope that museum curators will incorporate some of the odors into exhibits to make visits more immersive or memorable for museumgoers.

The three-year project, which is funded by the European Union, will also include a guide for how museums can use smells in exhibits. The use of smells in exhibits could also make museums more accessible for people who are blind or who have limited sight, historians said.

“Often museums are unsure of how to use smell in their spaces,” said Dr. William Tullett, an assistant professor of early modern European history at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England.

Plans for the project, which launches in January, began before the pandemic, but the researchers said the coronavirus, which has changed the smells of cities and can lead to a loss of smell for some people infected with it, has illustrated how scents and societies reflect each other.

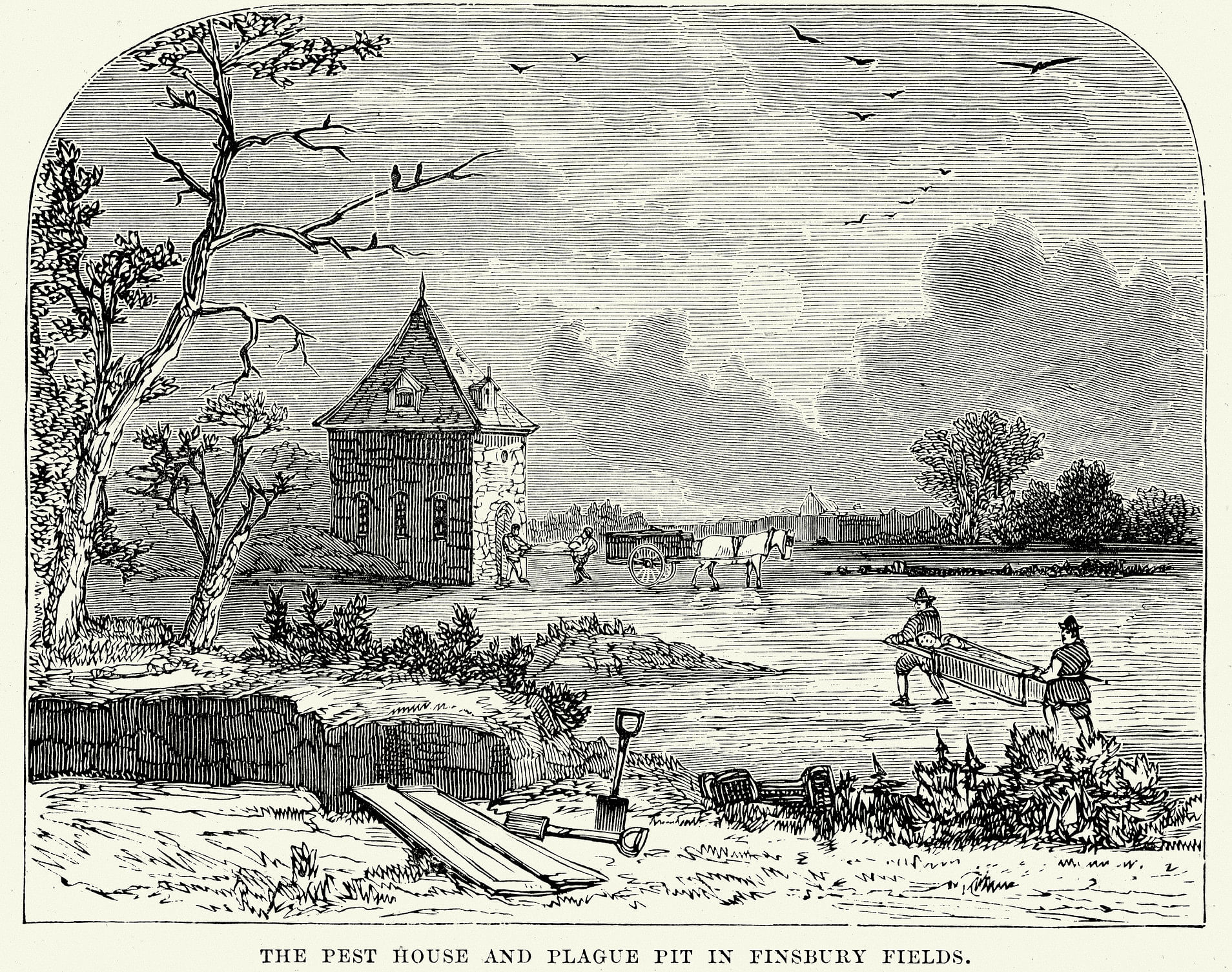

During past pandemics, the theory of miasma, which held that bad fumes were markers of disease transfer, was central to how people viewed the spread of infection.

Now, once again, people are especially attuned to the smells around them and sometimes worry that if they can smell someone standing nearby, then that person is in their aerosol environment and therefore too close, said Dr. Inger Leemans, a professor of cultural history at Vrije University Amsterdam. “Yet again, smell becomes an indicator of possible disease and infection.”

And lockdown measures have changed city scents, with fewer cars on the road and fewer smells wafting into the streets from restaurants. The changes, researchers said, highlight how studying smells in communities over time gives clues about historical attitudes to disease and other cultural aspects of daily life. The sense has been largely overlooked in academia but has received more attention in the last decade.

“With smell, you can open up questions about national culture, global culture, differences between communities, without immediately going into fights,” Leemans said, adding that introducing smells into museum exhibits or classrooms leads people to open up in discussions in ways they do not always do when discussing other issues of national identity. “It is such an open topic, and it has a large exploratory and communicative aspect to it.”

Leemans said researchers are not just interested in studying the good aromas of past centuries but also the bad smells, like dung or the stenches of industrialization and the sewage issues that plagued some European cities. They, too, can be dispensed in museums to help people connect with the past, so long as they do not scare visitors away.

“What we want to do is think, together with olfactory artists, about how you can bring that story to the nose — how do you make people realize what it is we did with industrialization in Europe,” Leemans said. “That’s the challenge.”