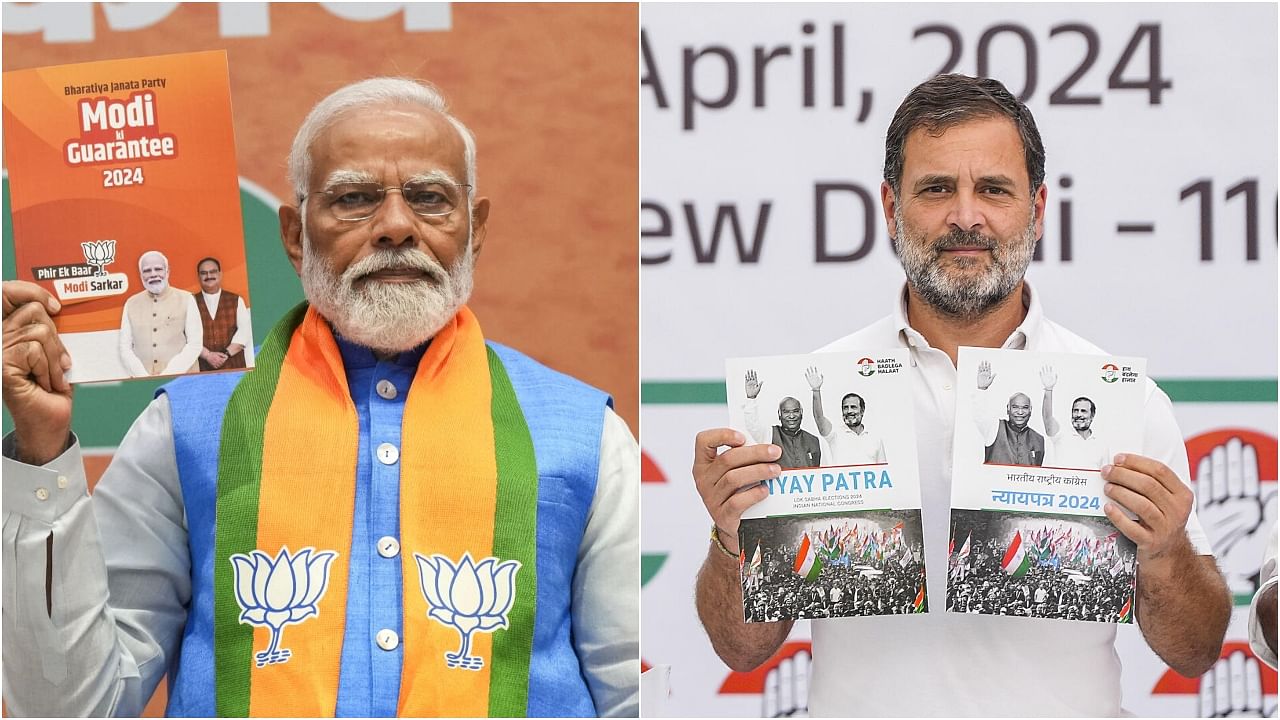

PM Narendra Modi with BJP's poll manifesto (L) and (R) Rahul Gandhi poses with the Congress manifesto for Lok Sabha polls.

Credit: PTI File Photos

There is a lot of noise and confusion being created over an inheritance tax in India. This is an attempt by the BJP to recover ground in an election that was believed to be in the bag, but is now seeming to be hotly contested.

Note the dramatic turn in the campaign tone and tenor in the last week alone.

First, the BJP’s ‘char-sau paar’ (400-plus seats) slogan raised fears about the party’s intentions and the risk of constitutional changes that such a large mandate would allow. Second, the Ram temple at Ayodhya, now that it is a reality, is not a hot election subject. Third, thorny issues like unemployment, price rise, the track record of candidates and inequality have raced ahead on the election agenda.

It is in this context that the Prime Minister turned to scaremongering over the bogey of an inheritance tax at an election rally in Rajasthan. He added to it a dose of communal hatred by saying wealth will be taken away and distributed among the minorities. The statement, in its entirety, is patently false, extremely divisive and wildly out of place. It takes public conduct to a new low.

What really is the issue at the heart of an inheritance tax? It should be clear that the Congress has not said it would impose such a tax.

Indeed, it was the Congress government of Rajiv Gandhi that scrapped the tax, effective March 16, 1985, when V P Singh was the finance minister. Speaking in Parliament, Singh had said: “While the yield from estate duty is only about Rs 20 crores, its cost of administration is relatively high. I, therefore, propose to abolish the levy of estate duty…”

In today’s context, the word “inequality” itself appears eight times in the 48-page Congress manifesto titled ‘Nyay Patra’. Most references talk about efforts to reduce wealth inequality, which has been the theme of Rahul Gandhi’s campaign.

In contrast, the word “inequality” does not feature in the BJP’s 76-page manifesto.

Approach towards inequality

The differences in language highlight the deep differences in policy approaches between the two leading parties in the election.

The BJP has been accused of increasing wealth inequality and further favouring a chosen few business leaders and families while increasing the tax burden on ordinary citizens using the GST to tax common people.

This is a point the Congress highlights by noting: “The share of taxes paid by the common person and the poor through regressive indirect taxes has increased significantly and the share of taxes paid by corporates has decreased – the exact opposite of what a people-friendly and progressive taxation policy should be.”

The Congress thus appears to attack the obscene wealth and income inequality which was brought to the world’s attention by the March 2024 report of the World Inequality Database, where the title of the paper itself tells the story: ‘Economic Inequality in India: The ‘Billionaire Raj’ is now more unequal than the ‘British colonial Raj’.

The research is authored, among others, by Thomas Piketty, the French academic noted for his global work on inequality. The paper notes that a “super tax” of just 2% on precisely 167 of the wealthiest families in 2022-23 would yield a remarkable “0.5% of national income in revenues and create valuable fiscal space to facilitate … investments (in health, education and nutrition)”. The paper found “suggestive evidence that the Indian income tax system might be regressive when viewed from the lens of net wealth”.

In the hypothetical situation of an inheritance tax making a comeback, it too, would impact only the ultra-rich, typically a small sliver of the top 1% in the economy.

This would not be a bad idea, as it would signal corrective action in the face of lopsided development and a jobless growth that has become the hallmark of the India GDP story.

Thus, such a tax would take the colour of an Ambani-Adani tax. It would signal the government’s resolve to strike at rising income and wealth inequality that in any case cannot continue without causing social and political disorder in the country.

Presented as a tax that would target the ultra-rich — say, the top 200 to 500 families of India, it would without doubt be a change that a large majority of India would welcome. Economists like Kaushik Basu have already said this would be a welcome tax.

Even in the US, avowedly a democratic capitalist political-economic system with a premium on individualism and wealth accumulation, there is an estate tax in place ranging from 18 to 40%. The rates and thresholds can change; in 1935, for example, the highest estate tax rate in the US was 70%.

Under the current US code, the tax has a threshold of $13.6 million. Any inheritance above this threshold is taxed. The amount typically moves up every year. A decade ago, the threshold was set at $5.34 million.

Estate tax is seen as a progressive tax, and is a part of the tax code also across Europe and in the UK.

In the words of Gandhi

What is probably not highlighted in the current debate is that Mahatma Gandhi had an even more radical view on not just inheritance but on capital itself. In one interview, Gandhi, instead of celebrating growth, asked the question: “How does one overcome weedy and unwieldy growth?” His model of trusteeship was very clear that the wealth did not belong to the shareholder but to society. In that sense, Gandhi was the earliest proponent of the stakeholder theory and had put forth his views in no uncertain terms long before the word “sustainability” had become the topic of business and political discussions across the globe.

Gandhi used the word “theft” to describe those taking more resources than they would need for their immediate and personal use. Here is Gandhi elaborating the point: “Whoever appropriates more than the minimum that is really necessary for him is guilty of theft.” His theory of trusteeship runs like this, as he offers in his journal, Harijan, dated June 3, 1939: “Supposing I have come by a fair amount of wealth – either by way of legacy, or by means of trade and industry — I must know that all that wealth does not belong to me; what belongs to me is the right to an honourable livelihood, no better than that enjoyed by millions of others. The rest of my wealth belongs to the community and must be used for the welfare of the community.”

Not one to make a point once and rest over it, Gandhi spoke repeatedly on the topic. On December 16, 1939, he wrote in Harijan, “…many capitalists are friendly towards me and do not fear me. They know that I desire to end capitalism, almost, if not quite, as much as the most advanced socialist or even communist. But our methods differ, our languages differ. My theory of trusteeship is no makeshift, certainly no camouflage. I am confident that it will survive all other theories. It has the sanction of philosophy and religion behind it…No other theory is compatible with non-violence.”

Linking wealth accumulation to violence against society is a deep Gandhian thought, a striking insight into ideas that go beyond manifest violence and bring to the table ideas like structural violence that denies opportunities, growth and fulfilment to those who remain poor while the nation celebrates “growth”.

In the India of today, where Gandhi has been pushed aside, and even abused and denigrated by the power structures that are taking the country toward a very different direction, the force of Gandhi and the power of his truth are speaking up. In many of the debates that have come up with the talk of an inheritance tax today, Gandhi and this thinking stand tall.

(The writer is a journalist and faculty member at S P Jain Institute of Management and Research, Mumbai. Views are personal)