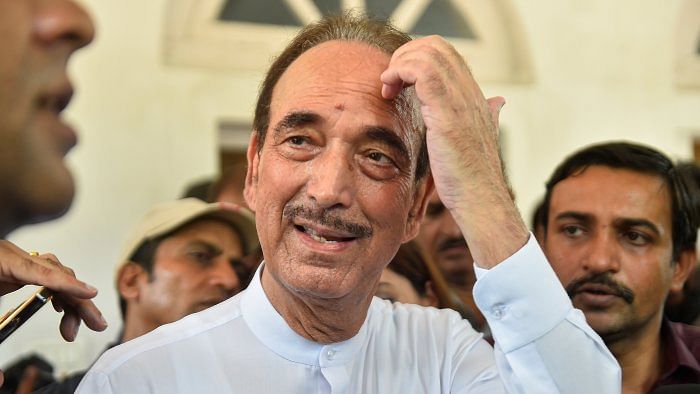

After the release of his autobiography Azaad on April 5, Ghulam Nabi Azad is basking in media attention. Media focus has been guaranteed by expectation of complimentary references to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and criticism of the opposition party, the Congress, both amounting to music to the mainstream media ears.

In being part of the rebel group, G23, in the Congress against the tight control of the Gandhis — Sonia Gandhi, son Rahul Gandhi, and daughter Priyanka Gandhi Vadra — Azad had opened himself to inducement by the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), that is known for deftly leveraging dissent in other parties.

To clinch the move, Modi was effusive in his praise for Azad, when Azad was demitting his Rajya Sabha membership, along the way also conferring on him the Padma Bhushan.

This mutual admiration paved the way for Azad to help provide options to the ruling party in addressing the imbroglio in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Azad set up a new regional party, the Democratic Progressive Azad Party (DPAP), in expectation of Union Territory elections.

The move held out the promise of cutting into the Congress votes in the Jammu region, and that of the regional mainstream parties in the Valley. It enabled Azad to position himself for another shy at chief ministership with the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP)’s backing.

In the event, the anticipated election has not materialised, and the DPAP is in a limbo. That Azad has put out his autobiography suggests an end-of-political-road throwing in of the towel.

Azad served another useful purpose for the ruling party in his advocacy for return to statehood and realistically, to him, conceding that the earlier autonomous status was no longer possible. His endorsement helped the Center’s efforts to legitimise the August 5, 2019 move of the Centre by way of which J&K’s special status was rescinded.

Thus, Azad has remained marginal to the BJP-style peace process underway in J&K.

Incidentally, similar was the case in the peace process pursued under Manmohan Singh. Azad was then Chief Minister in the Congress’s stint during the Congress-People’s Democratic Party (PDP) coalition that won the 2002 elections.

The backdrop of the elections was the massive deployment of the Army on in Operation Parakram since the Parliament attack the previous December. Though an exercise of coercive diplomacy, it was extended to enable troops mobilised to stay on to secure conduct of a ‘free and fair’ election. Recall at the time the spike in terrorism on since the Kargil War.

The PDP, that took the chief ministership first, promised a ‘healing touch’. In a visit to the state that spring, Prime Minister Vajpayee set the stage for a peace process based on insaniyat. Vajpayee’s peace initiative included an outreach to Pakistan, resulting in an unwritten agreement on ceasefire that — though chequered — has lasted till date.

As Chief Minister, Azad had the benefit of ‘double engine’ governance since the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) was at the Centre.

The UPA kept up the momentum from the Vajpayee years on the peace process with Pakistan, with several rounds of talk in the composite dialogue format.

Internally, during Azad’s tenure, it held three rounds of round table talks and constituted five working groups, four of which presented their reports timely.

While military operations continued, the cumulative impact was in a salutary improvement in violence indices.

Peace was at hand. Yet, Azad spilt the milk.

He was pressed on by the Governor, a former military general at the fag-end of his tenure, into having his Cabinet allocate forest land in Sonamarg for the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board (SASB) to facilitate yatris. The Governor, with alleged Right-wing credentials, was appointed by the previous BJP government and was then Chairman of the SASB.

This led to the mid-year agitation in 2008 in Kashmir against the transfer of land. A mirroring agitation in favour of the transfer began in Jammu. With the PDP leaving the coalition in protest, Azad resigned. Eventually, a new Governor as chairman of SASB surrendered the land.

Thus, Azad was instrumental in undermining a promising peace process at the behest of hardline forces not interested in return of peace. The 2008 agitations proved a forerunner to the agitations in later years, including those in the late 2010s.

A Jammuite, Azad was less than sensitive, if not callous, to the sentiment the Kashmiris attach to land and its alienation, indicative of their worry over demographic change. This lack of empathy resurfaced in his seemingly readier-than-necessary acceptance of the dilution in status of J&K.

While Azad’s autobiography may present his side of the story — now that he is at the end of his political tether having little utility left for the BJP — he would be remembered in history for his less than stellar role in the two contrasting peace processes in J&K.

(Ali Ahmed is a freelance strategic analyst. Twitter: @aliahd66.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.