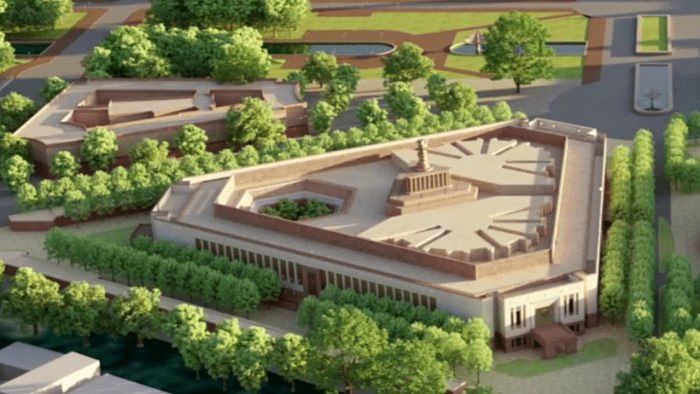

The inauguration of the new Parliament building on May 28 marks a watershed moment for Indian democracy. Over the years, calls for a new and modern building have found support from both sides of the political aisle because of the limitations of our existing Sansad Bhavan, which has been in use since 1927.

While the symbolic undertones of the transition have dominated media headlines, the building’s impact on the day-to-day life of a Member of Parliament (MP) deserves equal attention. The new building comes with several tech upgrades, including tablets for all MPs and the infrastructure to enable them to ‘Work From Anywhere’.

Beyond these functional enhancements, the transition is accompanied by proposals for more far-reaching changes. For example, the government is reportedly mulling allowing remote voting for the MPs, which can allow them to spend more time in their constituencies while also meeting their parliamentary obligations effectively. An Opposition MP also claimed that the government plans to increase the number of MPs from the current 800 to 1,000. This could allow the MPs to better represent voters by making constituencies somewhat smaller, and, thus, more manageable. Even the most well-intentioned plans to increase our MPs’ effectiveness, however, will have limited impact unless we address the structural barriers that constrain them.

Once we start looking at these barriers, we confront a harsh reality: our MPs are simply not given enough resources to do their jobs effectively. Every year, the MPs need to consider 50-60 Bills and study over 4,000 documents. Those who are on parliamentary panels have many additional meetings to attend and documents to review. In 2010-11, for example, the committee on agriculture held 40 meetings totalling 83 hours, and the material presented to them totalled over 4,300 pages. Add to this the time required for party work, election campaigns, and meeting voters from the constituency. To do all this, the MPs receive just Rs 30,000 per month to hire support staff, which is insufficient for even one high-quality resource.

Comparing this to other countries shows us how wide the gap truly is. In the United States, every senator receives enough funds to hire 30-40 staff members. In the United Kingdom, each MP has four to five support staff. But an Indian MP — who represents over 2.5 million people on average — is hamstrung by a lack of resources. Without additional help, we cannot expect the MPs to read legislative proposals, analyse their finer details, consult their constituents, and take a well-considered decision on how to vote. No amount of technology and automation can play this role effectively because it requires a careful analysis of multiple competing national and regional priorities.

However, adequate resourcing for our MPs is necessary but insufficient to unlock the full power of parliamentary processes. Over the decades, we have put restrictions on their voting behaviour that prevent them from independently applying their minds to an issue. The most insidious of these is the anti-defection law, which mandates that the MPs must vote according to the wishes of their political parties when asked to do so through the issuance of a whip. Since refusal to do so attracts disqualification from Parliament, almost all the MPs prefer to toe the party line.

This procedure exists in other parliamentary democracies as well, but only in India and a handful of other countries does it take this extreme form. In the UK, for example, violating even the most serious whip results in reduced prospects of promotion within the party or appointment to less-preferred roles in Parliament. In extreme cases, an MP may be removed from the party but they will continue to be in Parliament. This gives British MPs the freedom to take positions that may be different from those of their political bosses. In 2012, for example, 91 out of 306 Conservative MPs refused to support their own party’s proposal to reform the UK upper house.

While the anti-defection law was introduced with the well-intentioned objective of preventing the frequent rise and fall of governments, India is one of the very few countries in the world to extend it to all votes cast by an MP. This takes away any voting autonomy that the MPs may have, reducing their role in Parliament to merely executing decisions made by their political bosses.

Therefore, even as we look forward to inaugurating a new era for our Parliament, we must re-look at the limitations, both operational and structural, that reduce our MPs’ ability to effectively serve their role as the custodians of our vote and our voice.

(Subhashish Bhadra is Director, Klub, and author of Caged Tiger: How Too Much Government is Holding Indians Back.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.